By date

- 8 March 2021: Welcome!

- 9 March 2021: Kurt Weill and John Cale

- 18 March 2021: Happy Birthday, Kurt Weill!

- 26 March 2021: Working on "Mussel From Margate" and "Jealousy Duet"

- 03 April 2021: The Young Kurt Weill in Dessau

- 16 April 2021: Weill's Student years (1)

- 26 April 2021: Face-to-face!

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 20 May 2021: Novembergruppe

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 28 June 2021: Schickelgruber (song)

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 12 July 2021: What Is 'Epic Theater'?

- 15 July 2021: What Keeps Mankind Alive? (song)

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 25 July 2021: Speak Low (song)

- 2 August 2021: Youkali (song)

- 9 August 2021: François Villon

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 23 August 2021: Not exactly a manifesto

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 18 October 2021: Kurt Weill and shadow puppetry

- 25 October 2021: Summer 1933

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 8 November 2021: The Eternal Road

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 13 December 2021: One Touch of Venus

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 3 January 2022: Jewish Kurt Weill

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- 28 February 2022: Down in the Valley

- 14 March 2022: Love Life

- 28 March 2022: Lost in the Stars

Kurt Weill biography

- 03 April 2021: The Young Kurt Weill in Dessau

- 16 April 2021: Weill's Student years (1)

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 25 October 2021: Summer 1933

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 8 November 2021: The Eternal Road

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 13 December 2021: One Touch of Venus

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 3 January 2022: Jewish Kurt Weill

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- 28 February 2022: Down in the Valley

- 14 March 2022: Love Life

- 28 March 2022: Lost in the Stars

Lotte Lenya biography

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

By topic

- Agnes de Mille

- Alabama Song

- Alan Jay Lerner

- Alan Paton

- Arnold Sundgaard

- Baden-Baden

- Ben Hecht

- Berlin

- 16 April 2021: Weill's Student years (1)

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 20 May 2021: Novembergruppe

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- Berlin Im Licht

- Berliner Requiem

- Bertolt Brecht

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 12 July 2021: What Is 'Epic Theater'?

- 15 July 2021: What Keeps Mankind Alive? (song)

- 9 August 2021: François Villon

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- Broadway opera

- Caspar Neher

- Charles Lindbergh

- Complainte de la Seine

- Danny Kaye

- Darren Loucas

- David Drew

- Der Neinsager

- Der Protagonist

- Die Bürgschaft

- Down in the Valley

- Dresden

- East Portland Blog

- Elia Kazan

- Elisabeth Hauptmann

- Elmer Rice

- Engelbert Humperdinck

- Epic theater

- Erika Neher

- Erwin Piscator

- Eternal Road

- Expressionism

- Felix Jackson

- Firebrand of Florence

- Franz Werfel

- Frauentanz

- Fritz Busch

- Georg Kaiser

- George Antheil

- Georges Rouault

- Gertrude Lawrence

- Hannah Höch

- Hans Curjel

- Hollywood

- Hyperinflation

- Ira Gershwin

- Ivan Goll

- Jealousy Duet

- Jean Cocteau

- Jewish Kurt Weill

- Joe Mabel

- 8 March 2021: Welcome!

- 9 March 2021: Kurt Weill and John Cale

- 26 March 2021: Working on "Mussel From Margate" and "Jealousy Duet"

- 16 April 2021: Weill's Student years (1)

- 26 April 2021: Face-to-face!

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 20 May 2021: Novembergruppe

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 28 June 2021: Schickelgruber (song)

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 12 July 2021: What Is 'Epic Theater'?

- 15 July 2021: What Keeps Mankind Alive? (song)

- 25 July 2021: Speak Low (song)

- 2 August 2021: Youkali (song)

- 9 August 2021: François Villon

- 23 August 2021: Not exactly a manifesto

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 25 October 2021: Summer 1933

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 8 November 2021: The Eternal Road

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 13 December 2021: One Touch of Venus

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 3 January 2022: Jewish Kurt Weill

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- 28 February 2022: Down in the Valley

- 14 March 2022: Love Life

- 28 March 2022: Lost in the Stars

- Johann Gottfried Herder

- John Cale

- Juliana Brandon

- 8 March 2021: Welcome!

- 18 March 2021: Happy Birthday, Kurt Weill!

- 26 March 2021: Working on "Mussel From Margate" and "Jealousy Duet"

- 26 April 2021: Face-to-face!

- 28 June 2021: Schickelgruber (song)

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 25 July 2021: Speak Low (song)

- 2 August 2021: Youkali (song)

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 23 August 2021: Not exactly a manifesto

- 18 October 2021: Kurt Weill and shadow puppetry

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

- Kuhhandel

- Kurt Weill

- 8 March 2021: Welcome!

- 9 March 2021: Kurt Weill and John Cale

- 18 March 2021: Happy Birthday, Kurt Weill!

- 26 March 2021: Working on "Mussel From Margate" and "Jealousy Duet"

- 03 April 2021: The Young Kurt Weill in Dessau

- 16 April 2021: Weill's Student years (1)

- 26 April 2021: Face-to-face!

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 20 May 2021: Novembergruppe

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 28 June 2021: Schickelgruber (song)

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 12 July 2021: What Is 'Epic Theater'?

- 15 July 2021: What Keeps Mankind Alive? (song)

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 25 July 2021: Speak Low (song)

- 2 August 2021: Youkali (song)

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 23 August 2021: Not exactly a manifesto

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 18 October 2021: Kurt Weill and shadow puppetry

- 25 October 2021: Summer 1933

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 8 November 2021: The Eternal Road

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 13 December 2021: One Touch of Venus

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 3 January 2022: Jewish Kurt Weill

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- 28 February 2022: Down in the Valley

- 14 March 2022: Love Life

- 28 March 2022: Lost in the Stars

- Léo Lania

- Lüdenscheid

- Lady in the Dark

- Langston Hughes

- Lost in the Stars

- Lotte Lenya

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- Lotte Reiniger

- Love Life

- Lys Symonette

- Mahagonny

- Man Without Qualities

- Marc Blitzstein

- Marlene Dietrich

- Mary Martin

- Maurice Abravanel

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- Max Reinhardt

- Maxwell Anderson

- Meyer Weisgal

- Moss Hart

- Mussel From Margate

- Nazizeit

- New York

- One Touch of Venus

- Otto Dix

- Otto Pasetti

- Paris

- Princess du Polignac

- Robert Vambery

- Roger Fernay

- S.J. Perelman

- Scherenschnitte

- Schickelgruber

- Seven Deadly Sins

- Shadow puppetry

- Silbersee

- Street Scene

- Threepenny Opera

- Tilly Losch

- Weill Project

- 8 March 2021: Welcome!

- 9 March 2021: Kurt Weill and John Cale

- 18 March 2021: Happy Birthday, Kurt Weill!

- 26 March 2021: Working on "Mussel From Margate" and "Jealousy Duet"

- 26 April 2021: Face-to-face!

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 28 June 2021: Schickelgruber (song)

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 15 July 2021: What Keeps Mankind Alive? (song)

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 25 July 2021: Speak Low (song)

- 2 August 2021: Youkali (song)

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 23 August 2021: Not exactly a manifesto

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 18 October 2021: Kurt Weill and shadow puppetry

- 25 October 2021: Summer 1933

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 8 November 2021: The Eternal Road

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 13 December 2021: One Touch of Venus

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 3 January 2022: Jewish Kurt Weill

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- 28 February 2022: Down in the Valley

- 14 March 2022: Love Life

- 28 March 2022: Lost in the Stars

- Weill Project Blog

- Weill family

- Weill's Second Symphony

- What Keeps Mankind Alive

- What Was Sent to the Soldier's Wife

- World War II

- World War II propaganda

- Young Kurt Weill

- Yvette Endrijautzki

- Zeitoper

- degenerate art

Tags

#kurtweill #alanjaylerner #lovelife #joemabel #weillproject #weillbio(Prior biographical posts on Weill: [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27].

Having written last time about the one Kurt Weill theater piece I don't particularly like, I will now try to write about the Weill theater piece I least know: Love Life (1948), written with Alan Jay Lerner 🔗.

Ray Middleton in I Dream of Jeanie, 1952. Cropped from Republic Pictures still.

(Public domain, copyright not renewed.)

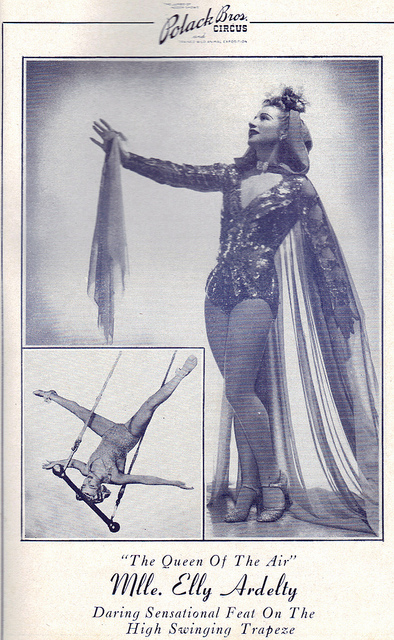

A publicity sheet for trapeze artist Elly Ardelty, a circus star who drew the third-highest salary in the original cast of Love Life.

(Believed to be public domain.)

Coming into Love Life, Weill and Lerner were both riding high. Lerner and Frederick Loewe had just had a hit with Brigadoon; Weill was coming off of his "Broadway opera" Street Scene, written with Elmer Rice and Langston Hughes, and his "American folk opera" Down in the Valley, written with Arnold Sundgaard. While neither of these was a Brigadoon-level hit, they were both quite commercially successful for pieces that did not fit at all easily into existing genres.

Apparently, everywhere that Weill and Lerner had control over it (e.g. the playbill), they wrote the title as "Love Life" rather than the more normal "Love Life", placing an abnormally big space between "Love" and "Life". As that suggests, Love Life, subtitled "A Vaudeville," was not exactly a conventional musical, and is certainly not as Currier-and-Ives cheery as a typical 1940s historical musical (I'm looking at you, Oklahoma!). Love Life is now seen as an early "concept musical," though the term wasn't around at the time. Weill's earlier piece with Ira Gershwin and Moss Hart, Lady in the Dark, which I wrote about late last year, was something of a concept musical, and certainly Rogers & Hammerstein's Allegro 🔗, which premiered in 1947 was as well. The least conventional Rogers & Hammerstein musical, Allegro had no sets (though it did use props and projections and the most elaborate lighting cues for any Broadway show up to that time). With its three "Greek choruses" (singing, dancing, speaking), it was basically R&H's one attempt at epic theater. Allegro was a middling commercial and critical success (though nothing next to many other Rogers & Hammerstein plays), but was an enormous inspiration to some of the next generation of writers of musicals, especially Stephen Sondheim 🔗. Hammerstein was a mentor, even a surrogate father, to Sondheim, and the 17-year-old Sondheim worked as a gofer for the production.

But back to Love Life. In 1947, Lerner was only 29 years old, one year older than Weill had been at the time of Threepenny Opera, and with Brigadoon already under his belt, and apparently having had some sort of temporary falling-out with Loewe, he came to Weill with a broad plot idea for a piece: the story of a marriage, disrupted by the Industrial Revolution. It's not clear how much connection Lerner and Weill might have had before this, but Weill's frequent conductor Maurice Abravanel had conducted Lerner and Loewe's The Day before Spring (1945). According to Joel Galand, when Loewe told Abravanel he didn't want to work with Lerner, Abravanel decided to properly introduce Lerner to Weill. (Oddly, Abravanel didn't end up involved in the resulting play.) In any case, the actual introduction seems to have been made by Cheryl Crawford, who had worked with Weill for over a decade and had produced both Lerner and Loewe's Brigadoon and Weill's One Touch of Venus. They started talking in March or April 1947, just before Weill headed off to Israel to see his parents.

Eventually, as they worked on the play, the "marriage disrupted by the Industrial Revolution" spread over the entire scope of the history of the United States. The marriage would begin in 1791, and the couple would be affected by 150 years or so of societal changes. This, of course, meant a totally non-naturalistic aspect that they would not age at the same pace time goes by. (Ultimately, it was decided that they would not visibly age at all.) Their marriage begins very hopefully in the early years of the Republic and slowly goes off the rails until a more-or-less present-day divorce. Weill liked the idea, and they spent the better part of a year turning it into a musical of sorts. And that subtitle, "A Vaudeville"? That wasn't in the original concept at all, but as they worked on the piece they decided to work in a variety of short theatrical pieces, many in the styles of the relevant eras. By the time the play solidified, there were ten of these pieces in Part I and six in Part II ("Part" rather than "Act", Weill and Lerner's decision, instead reserving "act" for the vaudeville sections, while the sections about the Cooper family are referred to as "sketches." Heady. Probably too heady.)

The play begins with one of these vaudeville segments, set in the then-present day. The two central characters are introduced by way of a magician using each of them as the subject of a magic trick. Susan Cooper is sawn in two, and her husband Samuel Cooper is left suspended in mid-air. Naturally, this is intended as a metaphor for their condition: Samuel rootless, and Susan divided in many ways ("half home-maker, half breadwinner; half lover and half provider; … over there a woman and up here a man"). Left in this situation by the magician, they begin to discuss the state of their marriage ("Fifty years ago? It was almost done then… A hundred years ago it was beginning to slip…") We then jump backward in time to the couple and their children, Johnny and Elizabeth, moving to "Mayville" in an unspecified part of the New England in 1791, and Sam opening a carpentry shop and committing himself, "Here I'll stay."

We move forward to 1821, when Sam closes his shop, seeing bigger possibilities in the Industrial Revolution. We see the first cracks in the marriage as Sam is unable to join Susan at a spring dance because he has to work late. In 1857, Sam takes a railroad job, which means he'll be often away from home. Susan wants another child, but Sam seems to evade the question. On one level it seems they don't have a third child but, still, three children, not two, sing "Mother's Getting Nervous," which segues into a ragtime number with a trapeze artist. (As far as I know, though, that third child never again appears. Oh, and the trapeze artist? For the first month of the Broadway production, it was Elly Ardelty, later inducted into the Circus Hall of Fame. Surprisingly little about her online, but she was a big enough star that she was the highest-paid cast member other than the two leads.) In the 1890s, Susan has become a suffragist. A hobo sings about love being the only answer, not anything in the social or economic sphere. He's ignored, and now Sam and Susan are on a New Year's Caribbean cruise in the 1920s; Sam is focused on business rather than on his wife; another businessman makes a pass at Susan, while Sam is tempted by a young blonde; ending Part I, they end up back with one another, but barely.

Part II begins in the present, 1948 in New York City. Sam works at a bank. Susan is a manager at a department store. We watch their chilly home life; a chorus performs what the Weill Foundation synopsis describes as "an Elizabethan-style a cappella madrigal about modern anxiety and neurosis," "Ho, Billy O!" 🔗, which I for one had never heard or even heard of until researching this. Things move toward separation and divorce, and to commedia dell'arte and Punch and Judy, and Sam moves into a hotel room, where (as the the Weill Foundation puts it) "he exults in his newfound bachelor freedoms," (but if you listen to "This Is the Life" 🔗, I don't hear much exulting).

The last portion of the play is a "minstrel show" about love and marriage (and about foolishness with respect to both). As in the initial vaudeville scene with the magician, Susan and Sam are pulled into this show-within-a-show, in this case as the "end men". (I could digress at such length here. If you want to know a ton about minstrel shows, read the Wikipedia article about them 🔗. If you just want these terms defined: during much of a minstrel show, the cast sat in a semi-circle, cracking jokes, singing songs, and doing small bits. The Interlocutor was sort of an emcee, and sat the middle. The End Men usually got the best zingers.) The Interlocutor addresses Susan and Sam and urge them to face reality. At the end of the play, Susan and Sam inch their way back toward one another on a tightrope.

The production brought together quite a solid team: Weill's frequent producer Cheryl Crawford 🔗, Elia Kazan 🔗 as director (despite his having felt micromanaged by Weill on One Touch of Venus, he actually postponed Death of a Salesman to work on this), Joseph Littau (less famous but with Carmen Jones and Carousel on his resume) as musical director, Nanette Fabray 🔗 (who, among other things, had studied with Max Reinhardt 🔗, Weill's collaborator on The Eternal Road) as Susan Cooper and Ray Middleton 🔗 (who had played Washington Irving in Knickerbocker Holiday) as Sam Cooper. Fabray, certainly worthy of the role, was not exactly a first choice: they had tried and failed to get, successively, Gertrude Lawrence (lead from Lady in the Dark), Mary Martin (lead from One Touch of Venus), and Ginger Rogers (lead from the rather dumbed-down film of One Touch of Venus).

The working title was A Dish for the Gods, a double allusion to Shakespeare: in Antony and Cleopatra, "I know that a woman is a dish for the gods, if the devil dress her not," but also in Julius Caesar Brutus, planning Caesar's murder, "Let's carve him as a dish fit for the gods". I think they moved to a better title, even if it is typographically tricky.

Apparently, Love Life underwent more changes in tryouts than anything else Weill ever worked on, and although it reached a pretty stable form by the time the New York rehearsals began, according to Joel Galand there were some cuts and additions even after the play opened. By Lerner's account "practically every scene in the play was rewritten and three completely new scenes were added." Two songs were written specifically for Fabray, and two more for Middleton, who was a Julliard-trained baritone. Some of this may have been because, as Charles Willard has observed 🔗, Sam and Susan are a bit weak as characters, a little too conceptual, and any good performance of the piece has to rely on the star quality of the actors who play these roles to make us care at all about them. From what I can tell, this is particularly true of Sam; the dropping of "Susan's Dream" from the Broadway production presumably made Nanette Fabray need to rely even more on charisma to make the audience care about Susan. (I found out only after writing that, from the Joel Galand piece 🔗 which I did not see until I was working on this blog entry: the first draft of the play centered much more on Susan, so she was the more thought-through character. As the play evolved, Lerner and Weill decided to make Sam an equal character, so they had to pare Susan back a bit. It's unsurprising that Sam never became quite as clear a character.) And, as with One Touch of Venus, Kazan and Weill clashed over the staging of musical numbers, with Kazan focused mainly on the aesthetics of how they would come off as visually naturalistic, while Weill was concerned about positioning singers to take best advantage of acoustics, and was much more willing than Kazan to be conventionally stage-y. (Fabray in a 1991 oral history interview seemed to think Weill understood a lot more than Kazan about staging a musical, especially when it came to non-naturalistic material like the minstrel show.)

Although Love Life certainly doesn't have the agit-prop aspect of Brecht's work, it is the most Brechtian, the most "epic" of Weill's American works. The "vaudeville" aspects (including the minstrel show that composes a large portion of Part II) and the impossible time scale definitely break any pretense of overall naturalism (though in general, the "sketches" about the family are, themselves, reasonably naturalistic). In the epic fashion, many of the songs bring up a broader, less personal context, or comment on the action rather than advancing it. Quite a few of the vaudeville "acts" are songs sung by choruses that do not otherwise participate in the plot. As Joel Galand writes, "The [vaudeville] songs comment on the socio-economic underpinnings of the ensuing sketch, either directly (as in the satirical 'Progress,' 'Economics,' 'Mother's Getting Nervous'), or obliquely, in a meditative or allegorical manner ('Love Song,' 'Madrigal: Ho, Billy O!'). These numbers tell us that the choices the protagonists, in their false consciousness, believe they are making as autonomous subjects are largely predetermined by their socioeconomic circumstances." Or to bring things all the way back to Die Bürgschaft (Weill with Caspar Neher in 1932), it is circumstances, not people, that change, and everything follows the law of money, the law of power. I have no idea how much of that was Weill's and how much was Lerner's; the piece appears to have been sufficiently a collaboration that they themselves might have had a hard time answering that question.

The play opened to great expectations: high ticket price, lots of buzz. Reviews were mixed; as Stephen Hinton remarks, "Critical assessment hinged largely on whether the lack of conventional plot structure was seen as a virtue or a vice." Brooks Atkinson didn't like it as a theater piece ("Vaudeville has nothing to do with the bitter ideas Mr. Lerner has to express about marriage"), but loved Weill's score: "hot, comic, blue, satiric, and romantic." There were a couple of months of sold-out houses, but then things fell off more rapidly than usual, and the play never recouped its initil investment. Weill, Lerner, Kazan, and choreographer Michael Kidd waived most of their royalties so that the investors wouldn't be totally burned, and it ran 252 performances, but there was no tour, no movie, no stock or amateur rights licensed, no published libretto, and above all (because of a particularly ill-timed American Federation of Musicians strike, the second "Petrillo Ban") no original cast album. I don't know why some of these things did (or didn't) happen; I do know that Lerner didn't want revivals, in no small part because it would inevitably result in attention to his own chaotic love life (married eight times). The first significant revival (University of Michigan, 1987) came the year after Lerner's death.

As far as I know, there is no official recording of Love Life available, and it has had few revivals; a 1996 BBC broadcast apparently is circulating in a bootleg, but I've never heard it. Quite a few songs can be found online:

- The first 22 minutes of the BBC production 🔗, including the first magician segment, "Who Is Samuel Cooper?", "My Name Is Samuel Cooper", "Here I'll Stay". This content overlaps the embedded video below.

- Progress 🔗, also from the BBC production

- I Remember it Well 🔗 (later reworked for Gigi), sung here by Thomas Hampson and Jeanne Lehman with the London Sinfonietta on Hampson's 1996 album Kurt Weill On Broadway

- Green-Up Time 🔗, also from the BBC production

- Susan's Dream 🔗, Shannon Forsell, who I didn't previously know and who does a great job on this. This song was dropped from the Broadway production, but apparently has been in most revivals.

- You Understand Me So 🔗, Keely Borland

- Love Song 🔗, sung by Richard Todd Adams. There is a more complete version in the embedded video below, Adams leaves out the initial verse.

- I'm Your Man 🔗, unknown provenance for the recording

- Ho, Billy O! 🔗, Gregg Smith Singers

- Is It Him Or Is It Me 🔗, Joy Bogen from the 2007 album Joy Bogen Sings Kurt Weill, obviously a lounge jazz reworking of the song.

- This Is the Life 🔗, Bryn Terfel with the English Northern Philharmonia, 1998

- Mr. Right 🔗, Lizzie Holmes, accompanied by Paul McKenzie.

In the course of researching this, I found 22 minutes of video excerpts from the 1987 production at the University of Michigan, which was the first proper revival of the play:

"My Name Is Samuel Cooper", "Here I'll Stay", "Economics", "Women's Club Blues", "Love Song."

The production number "Women's Club Blues" at 11:12 here is probably the most worth checking out.

All of which leaves me very much wanting to see a production of this, if there is ever a chance. There was supposed to be a revival in New York by NY City Center Encores in 2020, but because of the pandemic it was dropped in mid-rehearsal. The Kurt Weill Foundation has a nice web page about that 🔗 dating from while they still thought that was going to happen. It also includes BBC video excerpts of "This is the Life", "Mr. Right", and Nanette Fabray singing "Green-Up Time" on the Ed Sullivan Show in 1948.

[This essay draws heavily on Stephen Hinton's Weill's Musical Theater: Stages of Reform (University of California, 2012). The plot synopsis is drawn from

Next blog post: Lost in the Stars

Next Weill biography blog post: Lost in the Stars