By date

- 8 March 2021: Welcome!

- 9 March 2021: Kurt Weill and John Cale

- 18 March 2021: Happy Birthday, Kurt Weill!

- 26 March 2021: Working on "Mussel From Margate" and "Jealousy Duet"

- 03 April 2021: The Young Kurt Weill in Dessau

- 16 April 2021: Weill's Student years (1)

- 26 April 2021: Face-to-face!

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 20 May 2021: Novembergruppe

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 28 June 2021: Schickelgruber (song)

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 12 July 2021: What Is 'Epic Theater'?

- 15 July 2021: What Keeps Mankind Alive? (song)

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 25 July 2021: Speak Low (song)

- 2 August 2021: Youkali (song)

- 9 August 2021: François Villon

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 23 August 2021: Not exactly a manifesto

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 18 October 2021: Kurt Weill and shadow puppetry

- 25 October 2021: Summer 1933

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 8 November 2021: The Eternal Road

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 13 December 2021: One Touch of Venus

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 3 January 2022: Jewish Kurt Weill

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- 28 February 2022: Down in the Valley

- 14 March 2022: Love Life

- 28 March 2022: Lost in the Stars

Kurt Weill biography

- 03 April 2021: The Young Kurt Weill in Dessau

- 16 April 2021: Weill's Student years (1)

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 25 October 2021: Summer 1933

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 8 November 2021: The Eternal Road

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 13 December 2021: One Touch of Venus

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 3 January 2022: Jewish Kurt Weill

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- 28 February 2022: Down in the Valley

- 14 March 2022: Love Life

- 28 March 2022: Lost in the Stars

Lotte Lenya biography

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

By topic

- Agnes de Mille

- Alabama Song

- Alan Jay Lerner

- Alan Paton

- Arnold Sundgaard

- Baden-Baden

- Ben Hecht

- Berlin

- 16 April 2021: Weill's Student years (1)

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 20 May 2021: Novembergruppe

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- Berlin Im Licht

- Berliner Requiem

- Bertolt Brecht

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 12 July 2021: What Is 'Epic Theater'?

- 15 July 2021: What Keeps Mankind Alive? (song)

- 9 August 2021: François Villon

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- Broadway opera

- Caspar Neher

- Charles Lindbergh

- Complainte de la Seine

- Danny Kaye

- Darren Loucas

- David Drew

- Der Neinsager

- Der Protagonist

- Die Bürgschaft

- Down in the Valley

- Dresden

- East Portland Blog

- Elia Kazan

- Elisabeth Hauptmann

- Elmer Rice

- Engelbert Humperdinck

- Epic theater

- Erika Neher

- Erwin Piscator

- Eternal Road

- Expressionism

- Felix Jackson

- Firebrand of Florence

- Franz Werfel

- Frauentanz

- Fritz Busch

- Georg Kaiser

- George Antheil

- Georges Rouault

- Gertrude Lawrence

- Hannah Höch

- Hans Curjel

- Hollywood

- Hyperinflation

- Ira Gershwin

- Ivan Goll

- Jealousy Duet

- Jean Cocteau

- Jewish Kurt Weill

- Joe Mabel

- 8 March 2021: Welcome!

- 9 March 2021: Kurt Weill and John Cale

- 26 March 2021: Working on "Mussel From Margate" and "Jealousy Duet"

- 16 April 2021: Weill's Student years (1)

- 26 April 2021: Face-to-face!

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 20 May 2021: Novembergruppe

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 28 June 2021: Schickelgruber (song)

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 12 July 2021: What Is 'Epic Theater'?

- 15 July 2021: What Keeps Mankind Alive? (song)

- 25 July 2021: Speak Low (song)

- 2 August 2021: Youkali (song)

- 9 August 2021: François Villon

- 23 August 2021: Not exactly a manifesto

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 25 October 2021: Summer 1933

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 8 November 2021: The Eternal Road

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 13 December 2021: One Touch of Venus

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 3 January 2022: Jewish Kurt Weill

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- 28 February 2022: Down in the Valley

- 14 March 2022: Love Life

- 28 March 2022: Lost in the Stars

- Johann Gottfried Herder

- John Cale

- Juliana Brandon

- 8 March 2021: Welcome!

- 18 March 2021: Happy Birthday, Kurt Weill!

- 26 March 2021: Working on "Mussel From Margate" and "Jealousy Duet"

- 26 April 2021: Face-to-face!

- 28 June 2021: Schickelgruber (song)

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 25 July 2021: Speak Low (song)

- 2 August 2021: Youkali (song)

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 23 August 2021: Not exactly a manifesto

- 18 October 2021: Kurt Weill and shadow puppetry

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

- Kuhhandel

- Kurt Weill

- 8 March 2021: Welcome!

- 9 March 2021: Kurt Weill and John Cale

- 18 March 2021: Happy Birthday, Kurt Weill!

- 26 March 2021: Working on "Mussel From Margate" and "Jealousy Duet"

- 03 April 2021: The Young Kurt Weill in Dessau

- 16 April 2021: Weill's Student years (1)

- 26 April 2021: Face-to-face!

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 20 May 2021: Novembergruppe

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 28 June 2021: Schickelgruber (song)

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 12 July 2021: What Is 'Epic Theater'?

- 15 July 2021: What Keeps Mankind Alive? (song)

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 25 July 2021: Speak Low (song)

- 2 August 2021: Youkali (song)

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 23 August 2021: Not exactly a manifesto

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 18 October 2021: Kurt Weill and shadow puppetry

- 25 October 2021: Summer 1933

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 8 November 2021: The Eternal Road

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 13 December 2021: One Touch of Venus

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 3 January 2022: Jewish Kurt Weill

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- 28 February 2022: Down in the Valley

- 14 March 2022: Love Life

- 28 March 2022: Lost in the Stars

- Léo Lania

- Lüdenscheid

- Lady in the Dark

- Langston Hughes

- Lost in the Stars

- Lotte Lenya

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- Lotte Reiniger

- Love Life

- Lys Symonette

- Mahagonny

- Man Without Qualities

- Marc Blitzstein

- Marlene Dietrich

- Mary Martin

- Maurice Abravanel

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- Max Reinhardt

- Maxwell Anderson

- Meyer Weisgal

- Moss Hart

- Mussel From Margate

- Nazizeit

- New York

- One Touch of Venus

- Otto Dix

- Otto Pasetti

- Paris

- Princess du Polignac

- Robert Vambery

- Roger Fernay

- S.J. Perelman

- Scherenschnitte

- Schickelgruber

- Seven Deadly Sins

- Shadow puppetry

- Silbersee

- Street Scene

- Threepenny Opera

- Tilly Losch

- Weill Project

- 8 March 2021: Welcome!

- 9 March 2021: Kurt Weill and John Cale

- 18 March 2021: Happy Birthday, Kurt Weill!

- 26 March 2021: Working on "Mussel From Margate" and "Jealousy Duet"

- 26 April 2021: Face-to-face!

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 28 June 2021: Schickelgruber (song)

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 15 July 2021: What Keeps Mankind Alive? (song)

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 25 July 2021: Speak Low (song)

- 2 August 2021: Youkali (song)

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 23 August 2021: Not exactly a manifesto

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 18 October 2021: Kurt Weill and shadow puppetry

- 25 October 2021: Summer 1933

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 8 November 2021: The Eternal Road

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 13 December 2021: One Touch of Venus

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 3 January 2022: Jewish Kurt Weill

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- 28 February 2022: Down in the Valley

- 14 March 2022: Love Life

- 28 March 2022: Lost in the Stars

- Weill Project Blog

- Weill family

- Weill's Second Symphony

- What Keeps Mankind Alive

- What Was Sent to the Soldier's Wife

- World War II

- World War II propaganda

- Young Kurt Weill

- Yvette Endrijautzki

- Zeitoper

- degenerate art

Tags

#kurtweill #mosshart #iragershwin #mauriceabravanel #gertrudelawrence #dannykaye #ladyinthedark #newyork #joemabel #weillproject #weillbio

(Prior biographical posts on Weill: [1],

[2],

[3],

[4],

[5],

[6],

[7],

[8],

[9],

[10],

[11],

[12],

[13],

[14],

[15],

[16],

[17],

[18],

[19].

Sigmund Freud with his signature cigar. The musical Lady in the Dark took Freudian psychoanalysis as its theme.

Photo by Max Halberstadt, 1921. Now in the public domain.

Coming off of Knickerbocker Holiday and after the false start of Ulysses Africanus, Weill connected with playwright Moss Hart 🔗 to work on a play about Freudian psychoanalysis. Hart originally intended to write a straight play starring Katherine Cornell 🔗, and had approached Weill about writing incidental music. Before Weill even properly got started on that, Hart had evolved the idea into a musical to star Gertrude Lawrence 🔗, at which point the Hart and Weill successfully roped in lyricist Ira Gershwin 🔗. This was Gershwin's return to Broadway after his brother's death in 1937.

Lady in the Dark is both determinedly modern and now very dated. It has been revived a few times—most notably by London's Royal National Theater in 1999, which also resulted in a recording—but its theme of Freudian analysis, so current in 1941, is more than a bit dated now, as is the vulgar-Freudian conclusion of the play, which is sexist to the point of misogyny: protagonist Liza Elliott's ultimate "diagnosis" is that her outwardly successful—very successful—career is just a compensation for childhood trauma and a failure to accept her true womanly nature. At least one modern production (at the Hal Prince Theater in Philadelphia, 2001) cast a woman as the psychiatrist Dr. Brooks, which in some ways softens the play's misogyny, but (as Stephen Hinton points out) makes it even more the case that Brooks ought to know better.

Hart's generally favorable take on psychoanalysis was based on his own experiences as a patient of two celebrity psychoanalysts: Gregory Zilbourg 🔗 (whose other patients included George Gershwin 🔗 and Lillian Hellman 🔗) and Lawrence Kubie 🔗 (whose other patients included Vladimir Horowitz 🔗 and Tennessee Williams 🔗.) Kubie wrote extensively about the representation of psychiatry in film and theater. In his view, it was mostly misrepresentation, but he thought Hart got it about right, and Kubie even wrote a preface to the play under the name of the ficitonal Dr. Brooks. Kubie's only dissent from Hart's representation of the field was that things were too compressed in the chronology of the play, which he admitted was probably legitimate poetic license.

The books, films, and plays of the era contain plenty of representations of Freudian psychiatry (and even more use of its vocabulary), but according to Stephen Hinton, only one prior movie musical, and no theatrical musicals, had made it central to the plot. The one movie musical was the Ginger Rogers / Fred Astaire film Carefree 🔗 (1938), and while Hart seems to have cribbed a couple of plot elements from it (most notably the central female character's indecision about marriage), Carefree was much lighter fare than Lady in the Dark; it was pretty much a screwball comedy. Also, very unlike Lady in the Dark, in Carefree, the shrink—Fred Astaire—gets the girl. Talk about ethical issues…

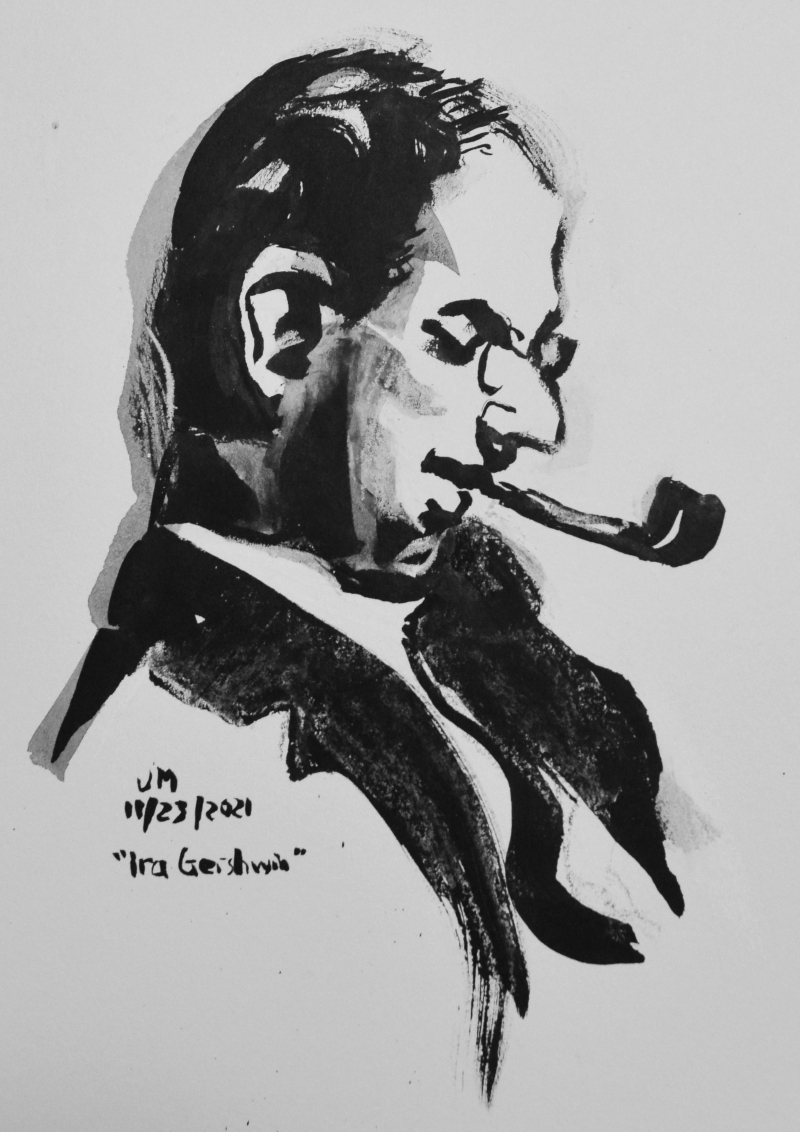

Ira Gershwin.

Drawing by Joe Mabel, 2021, based loosely on several photographs. All rights reserved.

Lady in the Dark, although by no means lightweight, certainly has plenty of comic elements, especially in the lengthy, over-the-top dream sequences that make up an enormous portion of the play. Weill really got a chance to act on his (and his mentor Ferruccio Busoni's—see earlier blog entry) view that the ideal role of music in theater was to express a "non-realistic, fantastical element" (Hinton's paraphrase). Dream logic created an enormous space for songs and production numbers without intruding on the relative realism of the rest of the play. Weill's music is central to the storytelling: the resolution of Liza's psychoanalysis comes when she can properly recall the song "My Ship", related to both pleasant and more-or-less traumatic aspects of Liza's childhood; she had repressed its memory, which she finally recovers in her last session with Dr. Brooks. By the time we finally hear the full song, the score has repeatedly prefigured it in fragments in the many dream sequences, where it presumably constituted "the return of the repressed" 🔗, in Freudian terms. Her assistant Charley Johnson also knows the song from his childhood, so the song is also the vehicle to bring them together as a couple (and in a power-sharing arrangement at the magazine).

For all of its Freudianism, the etiology of Liza's neurosis is rather non-sexual, more a matter of not getting adequate parental attention and support than anything else. Still, there is certainly a fair amount of coded and not-so-coded sexuality in Liza's dreams: for example, in the midst of her "Wedding Dream" of marrying her rather reserved publisher Kendall Nesbitt, who has left his wife for her, she fantasizes about a far more sexual relationship with a movie star, Randy Curtis. But, especially as Gertrude Lawrence played the role, Liza's main expression of sexuality comes late in the play, in the "Circus Dream". In an imaginary courtroom, she defends her own indecision by singing the "Saga of Jenny", a song about a woman whose decisiveness repeatedly leads to disaster. According to bruce mclung (no capitals there, his choice), who wrote an entire book about the play, Lawrence turned the piece into a burlesque-hall-style "bump and grind." It was apparently erotic enough that it encountered censorship issues when the show eventually went on tour and when Lawrence, outside of the show, performed the piece at concerts for members of the U.S. military. It looks like in all cases, some sort of compromise was reached.

Gertrude Lawrence on ABC Radio's Theatre Guild of the Air, 1947.

This anonymous 1947 photo was never copyrighted, so it is in the public domain.

Lady in the Dark also made a star out of Danny Kaye 🔗. He played a fashion photographer named Russell Paxton, who transforms into the "Ringmaster" during Liza's "Circus Dream". The Paxton character is definitely coded as gay: the script refers to him as "mildly effeminate in a charming manner." Although a moderately large role, Kaye/Paxton had only one song. Ira Gershwin dug up a piece of verse he had published in 1924 under the pseudonym Arthur Francis as "The Music Hour", reworked it a little, and Weill set it as "Tschaikowsky (and Other Russians)" (using the German spelling of the Russian composer's name). Lasting less than a minute, this patter song lists fifty Russian composers (actually, a few are Polish, but they lived in the era when Imperial Russia ruled Poland), and incorporates a theme from Tchaikovsky's Sixth Symphony. Kaye sang the song at such breakneck speed that it became clear in rehearsals that it had to be done as an a capella number, because there was no way for an orchestra to hold itself together without holding him back. Here he is some years later singing the song on the radio 🔗 with an orchestra that just about manages to stay with him. While we are at it, since I won't have a lot more excuses to mention Danny Kaye, here's a recording of my favorite routine of his, "Stanislavski" 🔗, a satire on method acting 🔗. Written by Kaye's wife Sylvia Fine, "Stanislavski" was part of their nightclub act at La Martinique, where Moss Hart saw them and decided to cast him in the Paxton role.

The play premiered 23 January 1941 at the Alvin Theatre, directed by Hassard Short and, like so many of Weill's works, conducted by Maurice Abravanel. Reviews were, in Jürgen Schebera's words, "effusive." Finally, after five and a half years in America, Weill had scored enough of a hit to make him financially independent for the first time since leaving Germany. Lady in the Dark ran for 467 performances at the Alvin, followed by a long, successful tour; Gertrude Lawrence stayed with it the whole way.

Like so many Broadway musicals, Lady in the Dark became the basis for a film (1944, starring Ginger Rogers and Roy Milland, directed by Mitchell Leisen). And like so many films of Broadway musicals, the resulting movie pretty much mangled the musical score, although "Saga of Jenny" did survive intact.

During much of the run of Lady in the Dark, Lenya was touring the U.S. in Maxwell Anderson's Candle in the Wind. We'll catch up with her later.

[This essay draws heavily on two excellent books, Jürgen Schebera's meticulously researched Kurt Weill: an illustrated life, (Yale, 1995, translated from the original German by Caroline Murphy) and Stephen Hinton's, Weill's Musical Theater: Stages of Reform (University of California, 2012).]

Next blog post: One Touch of Venus

Next Weill biography blog post: One Touch of Venus