By date

- 8 March 2021: Welcome!

- 9 March 2021: Kurt Weill and John Cale

- 18 March 2021: Happy Birthday, Kurt Weill!

- 26 March 2021: Working on "Mussel From Margate" and "Jealousy Duet"

- 03 April 2021: The Young Kurt Weill in Dessau

- 16 April 2021: Weill's Student years (1)

- 26 April 2021: Face-to-face!

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 20 May 2021: Novembergruppe

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 28 June 2021: Schickelgruber (song)

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 12 July 2021: What Is 'Epic Theater'?

- 15 July 2021: What Keeps Mankind Alive? (song)

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 25 July 2021: Speak Low (song)

- 2 August 2021: Youkali (song)

- 9 August 2021: François Villon

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 23 August 2021: Not exactly a manifesto

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 18 October 2021: Kurt Weill and shadow puppetry

- 25 October 2021: Summer 1933

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 8 November 2021: The Eternal Road

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 13 December 2021: One Touch of Venus

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 3 January 2022: Jewish Kurt Weill

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- 28 February 2022: Down in the Valley

- 14 March 2022: Love Life

- 28 March 2022: Lost in the Stars

Kurt Weill biography

- 03 April 2021: The Young Kurt Weill in Dessau

- 16 April 2021: Weill's Student years (1)

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 25 October 2021: Summer 1933

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 8 November 2021: The Eternal Road

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 13 December 2021: One Touch of Venus

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 3 January 2022: Jewish Kurt Weill

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- 28 February 2022: Down in the Valley

- 14 March 2022: Love Life

- 28 March 2022: Lost in the Stars

Lotte Lenya biography

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

By topic

- Agnes de Mille

- Alabama Song

- Alan Jay Lerner

- Alan Paton

- Arnold Sundgaard

- Baden-Baden

- Ben Hecht

- Berlin

- 16 April 2021: Weill's Student years (1)

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 20 May 2021: Novembergruppe

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- Berlin Im Licht

- Berliner Requiem

- Bertolt Brecht

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 12 July 2021: What Is 'Epic Theater'?

- 15 July 2021: What Keeps Mankind Alive? (song)

- 9 August 2021: François Villon

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- Broadway opera

- Caspar Neher

- Charles Lindbergh

- Complainte de la Seine

- Danny Kaye

- Darren Loucas

- David Drew

- Der Neinsager

- Der Protagonist

- Die Bürgschaft

- Down in the Valley

- Dresden

- East Portland Blog

- Elia Kazan

- Elisabeth Hauptmann

- Elmer Rice

- Engelbert Humperdinck

- Epic theater

- Erika Neher

- Erwin Piscator

- Eternal Road

- Expressionism

- Felix Jackson

- Firebrand of Florence

- Franz Werfel

- Frauentanz

- Fritz Busch

- Georg Kaiser

- George Antheil

- Georges Rouault

- Gertrude Lawrence

- Hannah Höch

- Hans Curjel

- Hollywood

- Hyperinflation

- Ira Gershwin

- Ivan Goll

- Jealousy Duet

- Jean Cocteau

- Jewish Kurt Weill

- Joe Mabel

- 8 March 2021: Welcome!

- 9 March 2021: Kurt Weill and John Cale

- 26 March 2021: Working on "Mussel From Margate" and "Jealousy Duet"

- 16 April 2021: Weill's Student years (1)

- 26 April 2021: Face-to-face!

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 20 May 2021: Novembergruppe

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 28 June 2021: Schickelgruber (song)

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 12 July 2021: What Is 'Epic Theater'?

- 15 July 2021: What Keeps Mankind Alive? (song)

- 25 July 2021: Speak Low (song)

- 2 August 2021: Youkali (song)

- 9 August 2021: François Villon

- 23 August 2021: Not exactly a manifesto

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 25 October 2021: Summer 1933

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 8 November 2021: The Eternal Road

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 13 December 2021: One Touch of Venus

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 3 January 2022: Jewish Kurt Weill

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- 28 February 2022: Down in the Valley

- 14 March 2022: Love Life

- 28 March 2022: Lost in the Stars

- Johann Gottfried Herder

- John Cale

- Juliana Brandon

- 8 March 2021: Welcome!

- 18 March 2021: Happy Birthday, Kurt Weill!

- 26 March 2021: Working on "Mussel From Margate" and "Jealousy Duet"

- 26 April 2021: Face-to-face!

- 28 June 2021: Schickelgruber (song)

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 25 July 2021: Speak Low (song)

- 2 August 2021: Youkali (song)

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 23 August 2021: Not exactly a manifesto

- 18 October 2021: Kurt Weill and shadow puppetry

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

- Kuhhandel

- Kurt Weill

- 8 March 2021: Welcome!

- 9 March 2021: Kurt Weill and John Cale

- 18 March 2021: Happy Birthday, Kurt Weill!

- 26 March 2021: Working on "Mussel From Margate" and "Jealousy Duet"

- 03 April 2021: The Young Kurt Weill in Dessau

- 16 April 2021: Weill's Student years (1)

- 26 April 2021: Face-to-face!

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 20 May 2021: Novembergruppe

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 28 June 2021: Schickelgruber (song)

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 12 July 2021: What Is 'Epic Theater'?

- 15 July 2021: What Keeps Mankind Alive? (song)

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 25 July 2021: Speak Low (song)

- 2 August 2021: Youkali (song)

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 23 August 2021: Not exactly a manifesto

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 18 October 2021: Kurt Weill and shadow puppetry

- 25 October 2021: Summer 1933

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 8 November 2021: The Eternal Road

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 13 December 2021: One Touch of Venus

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 3 January 2022: Jewish Kurt Weill

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- 28 February 2022: Down in the Valley

- 14 March 2022: Love Life

- 28 March 2022: Lost in the Stars

- Léo Lania

- Lüdenscheid

- Lady in the Dark

- Langston Hughes

- Lost in the Stars

- Lotte Lenya

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- Lotte Reiniger

- Love Life

- Lys Symonette

- Mahagonny

- Man Without Qualities

- Marc Blitzstein

- Marlene Dietrich

- Mary Martin

- Maurice Abravanel

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- Max Reinhardt

- Maxwell Anderson

- Meyer Weisgal

- Moss Hart

- Mussel From Margate

- Nazizeit

- New York

- One Touch of Venus

- Otto Dix

- Otto Pasetti

- Paris

- Princess du Polignac

- Robert Vambery

- Roger Fernay

- S.J. Perelman

- Scherenschnitte

- Schickelgruber

- Seven Deadly Sins

- Shadow puppetry

- Silbersee

- Street Scene

- Threepenny Opera

- Tilly Losch

- Weill Project

- 8 March 2021: Welcome!

- 9 March 2021: Kurt Weill and John Cale

- 18 March 2021: Happy Birthday, Kurt Weill!

- 26 March 2021: Working on "Mussel From Margate" and "Jealousy Duet"

- 26 April 2021: Face-to-face!

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 28 June 2021: Schickelgruber (song)

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 15 July 2021: What Keeps Mankind Alive? (song)

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 25 July 2021: Speak Low (song)

- 2 August 2021: Youkali (song)

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 23 August 2021: Not exactly a manifesto

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 18 October 2021: Kurt Weill and shadow puppetry

- 25 October 2021: Summer 1933

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 8 November 2021: The Eternal Road

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 13 December 2021: One Touch of Venus

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 3 January 2022: Jewish Kurt Weill

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- 28 February 2022: Down in the Valley

- 14 March 2022: Love Life

- 28 March 2022: Lost in the Stars

- Weill Project Blog

- Weill family

- Weill's Second Symphony

- What Keeps Mankind Alive

- What Was Sent to the Soldier's Wife

- World War II

- World War II propaganda

- Young Kurt Weill

- Yvette Endrijautzki

- Zeitoper

- degenerate art

Tags

#kurtweill #jewishkurtweill #franzwerfel #meyerweisgal #maxreinhardt #eternalroad #paris #newyork #nazizeit #joemabel #weillproject #weillbio(Prior biographical posts on Weill: [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16]. Also, see this post on the Novembergruppe.)

Schloss Leopoldskron. Max Reinhardt bought this palace near Salzburg, Austria at the end of World War I and spent 20 years restoring it, only to have it confiscated by the Nazis after the Anschluss incorporated Austria into Nazi Germany.

Photo by Wikimedia Commons user Simon1976 🔗, used under a CC-BY-SA-3.0 license 🔗

In late 1933 in Paris, Weill received a commission for a pageant about the Jewish people. The piece was originally conceived under the title Der Weg der Verheißung ("The Way of the Covenant" or "The Road of Promise") but eventually was known as The Eternal Road. The idea grew out of a pageant The Romance of a People 🔗 that had been presented 3 July 1933 at the Chicago World's Fair. I would say that The Eternal Road "grew into something larger than anyone had imagined," but The Romance of a People, a one-time production, had featured 6,000 actors, singers, and dancers; The Eternal Road was not quite that grandiose. Still, it grew into something larger than any theater piece intented to be played night after night ever ought to be, and the title proved all too appropriate: it was not until January 1937 that The Eternal Road would have its first public performance. By then, it had brought Weill and Lenya to America, which they would adopt as their new homeland.

Because the project took years before reaching the stage, I've decided that rather than go strictly chronologically through those years of Weill's life, I'm going to write here mainly about this one project and then come back in my next blog post to talk about what else he was up to during these years.

As we discussed in our early blog posts, Weill's father was an Orthodox Jewish cantor but Weill himself, despite supporting himself at age 18 as choir director of a synagogue in Berlin-Friedenau, was largely a secular person. In December 1933, it had been roughly a decade since Weill had last written a work on specifically Jewish themes: toward the end of his studies under Ferruccio Busoni he wrote an a capella choral cycle based on the Lamentations of Jeremiah (see prior blog post), which was not performed in his lifetime. In the years of the Weimar Republic, he clearly identified more as a German, a socialist, and of course a composer and a member of the artistic avant garde, than specifically as a Jew. Of course those various identities were very compatible with being a secular ethnic Jew: composer and teacher Arnold Schoenberg was also ethnically Jewish; Weill's sometime conductor Hans Curjel was a practicing Jew; Brecht's other most notable musical collaborator Hanns Eisler had a Jewish father; etc. When the Nazis attacked what they called "degenerate art" 🔗 ("Entartete Kunst") they had no difficulty coming up with a long list of Jewish "degenerate artists". But the fact remains: Weill was little enough connected to the Jewish community as such during this period of his greatest fame that it took a pretty serious discussion 🔗 to get even a mention of his Jewishness into the lede of the article about him in the English-language Wikipedia.

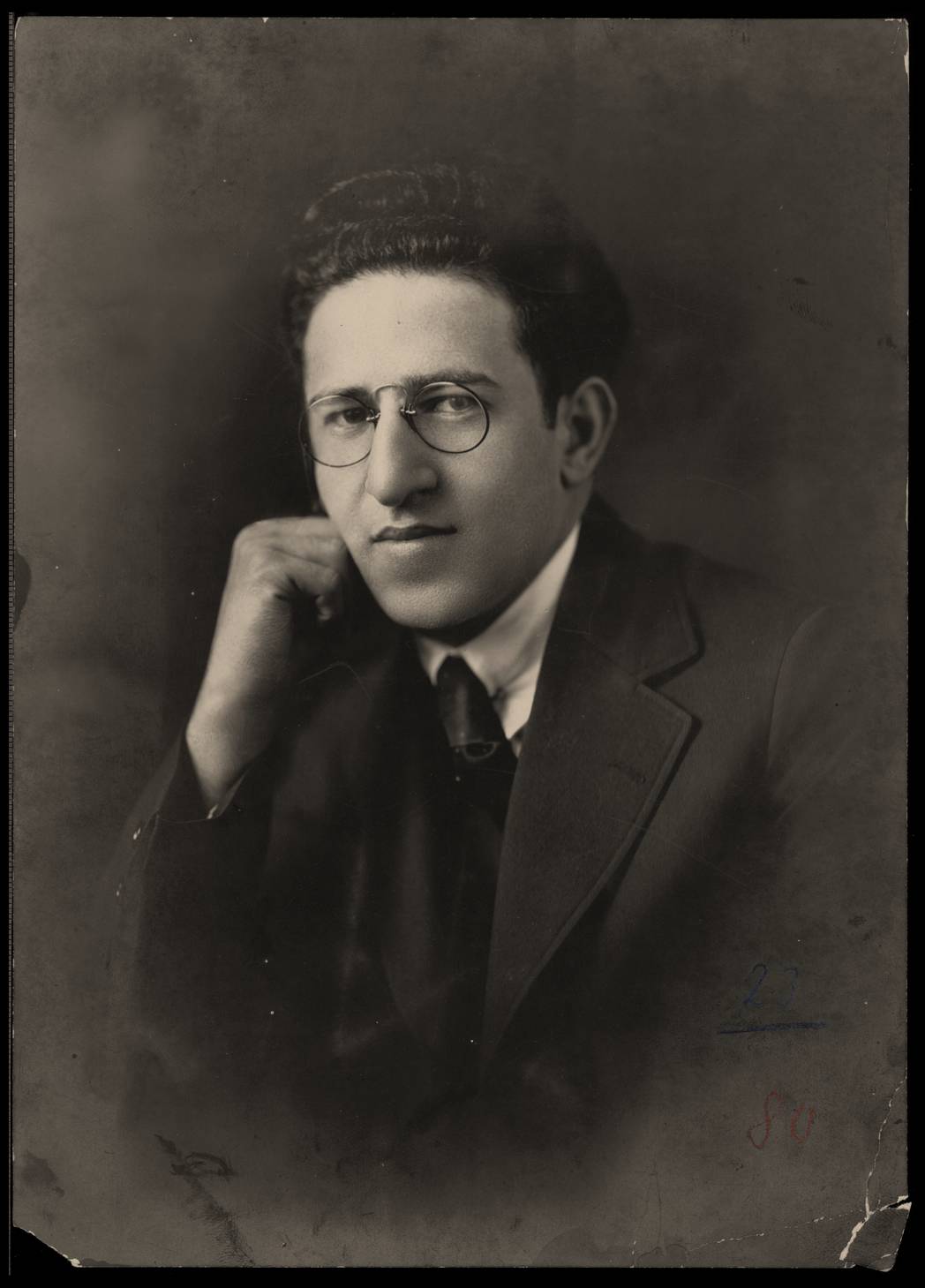

Meyer Weisgal

Photo published by the National Library of Israel under a CC-BY-SA-3.0 license 🔗; may be public domain.

Max Reinhardt

Photo by Nicola Perscheid, now public domain.

Franz Werfel

Photo by Carl Van Vechten, now public domain.

Norman Bel Geddes

Photo by Francis Bruguière, now public domain.

Weill clearly understood and agreed with what may be my favorite quotation from Hannah Arendt 🔗: "When you are attacked as a Jew, you must defend yourself as a Jew." No hiding behind a universalism that minimizes your Jewishness, nor an exceptionalism that distances yourself from other Jews. It was 1933. Hitler was chancellor of Germany, and consolidating his power in Germany into a dictatorship, and the Jews of Germany were under attack (as the Jews of the rest of Europe would soon be). It was time for Weill to turn to a specifically Jewish project.

As remarked above, the idea for The Eternal Road grew out of a pageant at the 1933-1934 Chicago World's Fair. Like that earlier pageant it had initial funding from several American Jewish organizations. Meyer Weisgal 🔗, head of the Zionist Organization of America and the impresario of The Romance of a People, reached out to producer-director Max Reinhardt 🔗 in November 1933 in Paris. Reinhardt recommended Franz Werfel 🔗 as librettist and Weill as composer; they contacted Weill in December 1933 and the three (along with Reinhardt's assistant Rudolph Kummer) met twice in summer 1934, once in Venice and once at Schloss Leopoldskron, Reinhardt's residence near Salzburg, Austria. Reinhardt, Weill, and Werfel were all ethnically Jewish; none were practicing Jews. As Weisgal put it, referring to the meeting at Reinhardt's home, "three of the best-known un-Jewish Jewish artists, gathered in the former residence of the Archbishop of Salzburg, in actual physical view of Berchtesgaden, Hitler's mountain chalet across the border in Bavaria, pledged themselves to give high dramatic expression to the significance of the people they had forgotten about till Hitler came to power."

Unsurprisingly, Weill wanted an oratorio, and Werfel wanted a largely spoken drama; Reinhardt convinced the two of them to collaborate on something more like an opera. Over the next few months, Weill wrote down every Jewish melody he knew (over 200 pieces), then researched to find out which were from before 1700, because he wished to avoid music that had borrowed from "opera, 'hit-songs' of the time, street tunes, concert music, symphonies." On 6 October 1934 he wrote that he had composed more than half of the specifically "musical" parts (as against those that would need joint work). That was probably optimistic: he was still fully plunged into the project in August 1935, when there was a further meeting at Schloss Loepoldskron after Reinhardt returned from working in the U.S. on a film of Shakespeare's Midsummer Night's Dream.

At this time the premiere of what was still called Der Weg der Verheißung was planned for December 1935 at the Manhattan Opera House (now Manhattan Center 🔗, owned, oddly, by the Unification Church, the followers of Sun Myung Moon); this occasioned Weill and Lenya's move to America. It may not have been clear at the time how permanent that move was to be, but the couple traveled from Cherbourg to New York City aboard the SS Majestic, arriving in New York 10 September 1935. As in Paris, he (and Lenya) initially settled into a good hotel; as in Paris, things did not go entirely well, and they had to "downsize". Unlike Paris, Weill arrived in New York almost unknown outside of avant garde music circles. We'll get more into that in a future blog post; for now, let's stick with The Eternal Road.

Weisgal engaged Oskar Strnad 🔗 as a stage designer, Ludwig Lewisohn 🔗 as a translator, and Charles Alan (about whom I know nothing) to write some additional lyrics. Lewisohn and Alan's work appears to have gone smoothly, but Strnad fell ill and had to leave the project; by the time it premiered, he had died. To replace Strnad, Reinhardt brought in Norman Bel Geddes 🔗. As Jürgen Schebera put it, this "assured the project monumental greatness but also financial ruin." Bel Geddes's plans were, as Guy Stern would write, "grandiose (if not megalomaniac)," and "required complete rebuilding of a theater." Weisgal liked this all too much.

The Eternal Road alternates between prose scenes set in a present-day synagogue endangered by the Nazis and verse scenes from Bible stories. The synagogue scenes are on a "chamber" scale and use the Jewish melodies Weill had researched; the Biblical scenes are arranged as a "large oratorio." Bel Geddes's plan for staging this involved an almost total rebuild of the Manhattan Opera House, leaving little in place but the outer walls. The synagogue itself sat where the first several rows of seats had previously been, so the theater capacity was diminished. A curving road led up a "mountain" from the synagogue past where the orchestra pit had been removed, and ascended a sloped stage. On this stage were, at various times, 240 actors, forty dancers, and a hundred singers. There are 30 "solo" roles. Bel Geddes' design did not leave room for an orchestra: he wanted to use recorded music. Weill, of course, strongly objected. A compromise was ultimately reached: large portions of the orchestration were prerecorded (using the cinema technology of the day), but there was an onstage ensemble.

The piece premiered 4 January 1937, over three years after Weill had initially signed on. The production marked Lenya's first performance on an American stage, cast as the biblical prophetess Miriam, sister of Moses. On the first night, the four-act play/pageant/opera ran until 3 in the morning; the critics all left after Act II to write their reviews on deadline, but those reviews were uniformly raves, and for the rest of the run the piece was chopped down to its first two acts. Typical of the reviews was Brooks Atkinson 🔗 in the New York Times: "After an eternity of postponements The Eternal Road has finally arrived at the Manhattan Opera House… Let it be said at once that the ten postponements are understood and forgiven. Out of the heroic stories of old Jewish history Max Reinhardt and his many assistants have evoked a glorious pageant of great power and beauty." Several reviewers noted, in particular, Weill's enormous breadth, that he could compose both this and the music for Johnny Johnson, which was running elsewhere on Broadway at the time and which we will take up in our next biographical blog post on Weill.

The Eternal Road ran 153 performances, all to full houses, but the economics were insane. Even with full houses, the production lost $5000 every week. The piece would not be performed again in anything like its entirety until 13 June 1999 when the Chemnitz Opera in Germany performed it as part of the centennial celebrations of Weill's birth. That 1999 performance also constituted the very belated premiere of Werfel's original German-language libretto. The piece has since been performed several times; extensive excerpts have been recorded; I don't believe it has ever been recorded in its entirety. Excerpts in this short online documentary 🔗 give some sense of the music. I just ordered the CD by the Berlin Philharmonic, conducted by Gerard Schwarz, but I've never really heard more than a few extracts, so I can't claim any independent opinion about the piece beyond a desire to hear it.

The Eternal Road was a great critical success, but provided Weill little money, and it never again played in his lifetime. Meanwhile, his parents had escaped Germany to Palestine, and his finances had to include supporting them.

Two weeks after the premiere, Weill and Lenya remarried 19 January 1937 in North Castle, a small town in Westchester County, New York. The wedding was low-key, because they had little money. After the wedding, rather than any sort of honeymoon, Weill headed to Hollywood with Cheryl Crawford 🔗 of the Group Theatre 🔗 (more on the Group Theatre when we take up the rest of what was happening in these years) while Lenya borrowed Crawford's Beekman Place apartment with a view of the East River, and continued to sing the role of Miriam for the next several months.

[This essay draws heavily on Jürgen Schebera's meticulously researched Kurt Weill: an illustrated life, (Yale, 1995, translated from the original German by Caroline Murphy). I've also drawn a few facts, especially about production history, from the Wikipedia article on The Eternal Road 🔗 and from this excellent article from WTTW Chicago about The Romance of a People.]

Next blog post: New York, New York

Next Weill biography blog post: New York, New York