By date

- 8 March 2021: Welcome!

- 9 March 2021: Kurt Weill and John Cale

- 18 March 2021: Happy Birthday, Kurt Weill!

- 26 March 2021: Working on "Mussel From Margate" and "Jealousy Duet"

- 03 April 2021: The Young Kurt Weill in Dessau

- 16 April 2021: Weill's Student years (1)

- 26 April 2021: Face-to-face!

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 20 May 2021: Novembergruppe

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 28 June 2021: Schickelgruber (song)

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 12 July 2021: What Is 'Epic Theater'?

- 15 July 2021: What Keeps Mankind Alive? (song)

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 25 July 2021: Speak Low (song)

- 2 August 2021: Youkali (song)

- 9 August 2021: François Villon

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 23 August 2021: Not exactly a manifesto

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 18 October 2021: Kurt Weill and shadow puppetry

- 25 October 2021: Summer 1933

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 8 November 2021: The Eternal Road

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 13 December 2021: One Touch of Venus

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 3 January 2022: Jewish Kurt Weill

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- 28 February 2022: Down in the Valley

- 14 March 2022: Love Life

- 28 March 2022: Lost in the Stars

Kurt Weill biography

- 03 April 2021: The Young Kurt Weill in Dessau

- 16 April 2021: Weill's Student years (1)

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 25 October 2021: Summer 1933

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 8 November 2021: The Eternal Road

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 13 December 2021: One Touch of Venus

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 3 January 2022: Jewish Kurt Weill

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- 28 February 2022: Down in the Valley

- 14 March 2022: Love Life

- 28 March 2022: Lost in the Stars

Lotte Lenya biography

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

By topic

- Agnes de Mille

- Alabama Song

- Alan Jay Lerner

- Alan Paton

- Arnold Sundgaard

- Baden-Baden

- Ben Hecht

- Berlin

- 16 April 2021: Weill's Student years (1)

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 20 May 2021: Novembergruppe

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- Berlin Im Licht

- Berliner Requiem

- Bertolt Brecht

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 12 July 2021: What Is 'Epic Theater'?

- 15 July 2021: What Keeps Mankind Alive? (song)

- 9 August 2021: François Villon

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- Broadway opera

- Caspar Neher

- Charles Lindbergh

- Complainte de la Seine

- Danny Kaye

- Darren Loucas

- David Drew

- Der Neinsager

- Der Protagonist

- Die Bürgschaft

- Down in the Valley

- Dresden

- East Portland Blog

- Elia Kazan

- Elisabeth Hauptmann

- Elmer Rice

- Engelbert Humperdinck

- Epic theater

- Erika Neher

- Erwin Piscator

- Eternal Road

- Expressionism

- Felix Jackson

- Firebrand of Florence

- Franz Werfel

- Frauentanz

- Fritz Busch

- Georg Kaiser

- George Antheil

- Georges Rouault

- Gertrude Lawrence

- Hannah Höch

- Hans Curjel

- Hollywood

- Hyperinflation

- Ira Gershwin

- Ivan Goll

- Jealousy Duet

- Jean Cocteau

- Jewish Kurt Weill

- Joe Mabel

- 8 March 2021: Welcome!

- 9 March 2021: Kurt Weill and John Cale

- 26 March 2021: Working on "Mussel From Margate" and "Jealousy Duet"

- 16 April 2021: Weill's Student years (1)

- 26 April 2021: Face-to-face!

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 20 May 2021: Novembergruppe

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 28 June 2021: Schickelgruber (song)

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 12 July 2021: What Is 'Epic Theater'?

- 15 July 2021: What Keeps Mankind Alive? (song)

- 25 July 2021: Speak Low (song)

- 2 August 2021: Youkali (song)

- 9 August 2021: François Villon

- 23 August 2021: Not exactly a manifesto

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 25 October 2021: Summer 1933

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 8 November 2021: The Eternal Road

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 13 December 2021: One Touch of Venus

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 3 January 2022: Jewish Kurt Weill

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- 28 February 2022: Down in the Valley

- 14 March 2022: Love Life

- 28 March 2022: Lost in the Stars

- Johann Gottfried Herder

- John Cale

- Juliana Brandon

- 8 March 2021: Welcome!

- 18 March 2021: Happy Birthday, Kurt Weill!

- 26 March 2021: Working on "Mussel From Margate" and "Jealousy Duet"

- 26 April 2021: Face-to-face!

- 28 June 2021: Schickelgruber (song)

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 25 July 2021: Speak Low (song)

- 2 August 2021: Youkali (song)

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 23 August 2021: Not exactly a manifesto

- 18 October 2021: Kurt Weill and shadow puppetry

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

- Kuhhandel

- Kurt Weill

- 8 March 2021: Welcome!

- 9 March 2021: Kurt Weill and John Cale

- 18 March 2021: Happy Birthday, Kurt Weill!

- 26 March 2021: Working on "Mussel From Margate" and "Jealousy Duet"

- 03 April 2021: The Young Kurt Weill in Dessau

- 16 April 2021: Weill's Student years (1)

- 26 April 2021: Face-to-face!

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 20 May 2021: Novembergruppe

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 28 June 2021: Schickelgruber (song)

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 12 July 2021: What Is 'Epic Theater'?

- 15 July 2021: What Keeps Mankind Alive? (song)

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 25 July 2021: Speak Low (song)

- 2 August 2021: Youkali (song)

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 23 August 2021: Not exactly a manifesto

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 18 October 2021: Kurt Weill and shadow puppetry

- 25 October 2021: Summer 1933

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 8 November 2021: The Eternal Road

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 13 December 2021: One Touch of Venus

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 3 January 2022: Jewish Kurt Weill

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- 28 February 2022: Down in the Valley

- 14 March 2022: Love Life

- 28 March 2022: Lost in the Stars

- Léo Lania

- Lüdenscheid

- Lady in the Dark

- Langston Hughes

- Lost in the Stars

- Lotte Lenya

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- Lotte Reiniger

- Love Life

- Lys Symonette

- Mahagonny

- Man Without Qualities

- Marc Blitzstein

- Marlene Dietrich

- Mary Martin

- Maurice Abravanel

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- Max Reinhardt

- Maxwell Anderson

- Meyer Weisgal

- Moss Hart

- Mussel From Margate

- Nazizeit

- New York

- One Touch of Venus

- Otto Dix

- Otto Pasetti

- Paris

- Princess du Polignac

- Robert Vambery

- Roger Fernay

- S.J. Perelman

- Scherenschnitte

- Schickelgruber

- Seven Deadly Sins

- Shadow puppetry

- Silbersee

- Street Scene

- Threepenny Opera

- Tilly Losch

- Weill Project

- 8 March 2021: Welcome!

- 9 March 2021: Kurt Weill and John Cale

- 18 March 2021: Happy Birthday, Kurt Weill!

- 26 March 2021: Working on "Mussel From Margate" and "Jealousy Duet"

- 26 April 2021: Face-to-face!

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 28 June 2021: Schickelgruber (song)

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 15 July 2021: What Keeps Mankind Alive? (song)

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 25 July 2021: Speak Low (song)

- 2 August 2021: Youkali (song)

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 23 August 2021: Not exactly a manifesto

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 18 October 2021: Kurt Weill and shadow puppetry

- 25 October 2021: Summer 1933

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 8 November 2021: The Eternal Road

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 13 December 2021: One Touch of Venus

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 3 January 2022: Jewish Kurt Weill

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- 28 February 2022: Down in the Valley

- 14 March 2022: Love Life

- 28 March 2022: Lost in the Stars

- Weill Project Blog

- Weill family

- Weill's Second Symphony

- What Keeps Mankind Alive

- What Was Sent to the Soldier's Wife

- World War II

- World War II propaganda

- Young Kurt Weill

- Yvette Endrijautzki

- Zeitoper

- degenerate art

Tags

#kurtweill #casparneher #erikaneher #johanngottfriedherder #diebürgschaft #joemabel #weillproject #berlin #weillbio(Prior biographical posts on Weill: [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11]. Also, see this post on the Novembergruppe.)

Film director G.W. Pabst and actor Albert Préjean, seen during the shooting of the French-language version of the Threepenny Opera film, L'Opéra de quat'sous, 1931. In those days before dubbing, issuing the film in German and French called for shooting with two separate casts.

(The anonymous photo is now in the public domain.)

The Grosse Mahagonny and Der Jasager were effectively the end of Weill's three-year collaboration with Bertolt Brecht. The pair would not again work together until the Nazis had come to power and both had fled Germany. Legend has it that Weill told the increasingly doctrinaire Brecht that he (Weill) "could not set the Communist Manifesto to music," though Caspar Neher's libretto for Weill's next major piece, Die Bürgschaft, comes as close to that as any work of Brecht's.

Although Weill and Brecht were both originally hired on for G.W. Pabst's film adaptation of the Dreigroschenoper ("Threepenny Opera"), they each separately fell out with Pabst. Brecht lost a lawsuit over Pabst's changes to his script, largely Pabst's rejection of some changes Brecht wanted to make. Weill, in contrast, won a similar suit over changes to his music, so while the film made major cuts to his score, what was used came through intact. The whole thing is rather complicated: Brecht himself had removed some songs Weill had wanted to keep. Brecht wrote an entire book about the affair, and the matter has been the subject of numerous theses and dissertations. While I'd love to learn more about all this and someday write intelligently about the matter, I don't see any need to detail my current ignorant perspective. Enough said.

The Great Depression was hard on theaters and even more so on opera. There was less state support and at the same time there was a diminished audience. Berlin's Krolloper, where Otto Klemperer conducted, closed permanently in July 1931. Surviving opera houses mover to what Jürgen Schebera describeds as "a 'marketable' repertoire of classics and light entertainment." Plus reactionary political parties and factions, and their paramilitaries, were getting stronger. Even so, Weill continued to advocate "large form" opera and theater "address[ing] the great questions of the day." Opera, he was soon to write, is a "heightened form of theater best suited to translate great ideas of the time into a timeless humanistic form," and he sought a suitable story and collaborator to continue to fulfill his ambitions along these lines.

Image of Good Soldier Schweik on a restaurant sign at Český Krumlov, a castle in the South Bohemia region of the Czech Republic. Jaroslav Hašek's 🔗 novel is consistently ambiguous as to whether the titular Schweik (Švejk in Czech) is a master of passive resistance or an incompetent fool; either way, his conduct constantly frustrates the intentions of his commanders.

(The image is based on Josef Lada's 🔗 illustrations for Hašek's book; the photograph by Wikimedia Commons User Electron 🔗 takes advantage of Freedom of Panorama in the Czech Republic to photograph the sign, and is used here under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license 🔗 offered by Electron.)

Weill considered several projects: Jaroslav Hašek's Good Soldier Schweik 🔗, a piece based on the works of Jack London 🔗, another piece drawing on Franz Kafka 🔗— what I wouldn't give to have that one!— but none of these got past the prospectus/sketch stage. His break with Brecht didn't mean a break with their mutual collaborators. He was spending a lot of time with Caspar Neher, who had designed the sets for most of the Brecht/Weill theater pieces, and was, as they say euphemistically, becoming very close with his Neher's wife Erika Neher. As I said a while back, surely somewhere in the story of 1920s Berlin and Paris were two people in a monogamous relationship with one another, but I cannot think who they would be. Certainly not the Nehers. And certainly not Weill and Lenya.

Neher suggested working on a piece based on a very short fable by Johann Gottfried Herder 🔗, "Der afrikanische Rechtsspruch" ("The African Verdict") written in 1774. The piece is so short that I might as well translate it right here; click here for the German original, for anyone who cares.

Alexander of Macedonia [that is, Alexander the Great - ed.] once came to a remote, gold-rich province of Africa; the inhabitants offered him bowls full of golden apples and fruit. "Do you eat these fruits with yourselves?" asked Alexander; "I did not come to see your riches, but to learn from your customs." So they took him to the market, where their king was holding court.

A citizen stepped forward and said, "Oh King, I bought a sack-full of chaff from this man, and found a considerable treasure therein. The chaff is mine, but not the gold; and this man won't take it back. Speak to him, Oh King, for it is his."

The seller, also a local citizen, opposed this and replied, "You are afraid of keeping something wrong; and shouldn't I be afraid to take such a thing from you? I sold you the sack and everything in it; keep what is yours. Speak to him, Oh King."

The king asked the first if he had a son. He replied: "Yes." He asked the other if he had a daughter and the answer was also yes. "Well then," said the king, "you are both righteous people: marry your children together and give them the treasure you have found as a wedding gift; This is my decision."

Alexander was astonished. "Have I judged wrongly," asked the king of the distant land, "so that you are astonished?" "Not at all," answered Alexander, "but in our country one would judge differently." "And how?" asked the African king." "Both contenders," said Alexander, "would lose their heads and the treasure would fall into the hands of the king."

The king clapped his hands and asked: "Does the sun shine on you too, and does the sky still rain on you?" Alexander replied: "Yes." "This must be," the king went on, "because of the innocent animals that live in your country; because over such people no sun should shine, no sky rain."

From this seed grew Die Bürgschaft ("The Pledge" or "The Guarantee"). Neher, mainly a stage designer although with some experience directing, took it upon himself to produce a libretto. In the late spring of 1931, Weill drove through France & Spain, where the Second Republic 🔗 had just been declared, a far more hopeful environment (for the moment) than what the faced in Germany. Neher joined him in Zazaux near San Sebastian, bringing a draft of the libretto, which they then reworked together.

By October 1931 they had completed Die Bürgschaft, an "epic opera" that vastly expands Herder's work. There are two commenting choruses, one of which is onstage. Characters often break from the plot and directly address audience, and at one point a large choral cantata interrupts the action. Weill makes some use of popular music styles, but little in the play is light or comic. The piece is certainly very theatrical, but there are fewer easy pleasures than in Weill's work with Brecht.

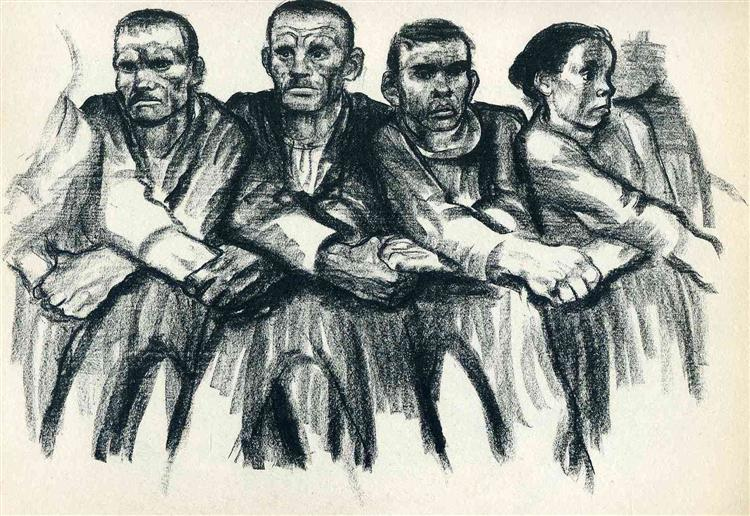

"Solidarity", a 1932 etching by Käthe Kollwitz 🔗.

(Public domain.)

Solidarity of another sort. A campaign poster supporting Hindenburg 🔗 in the 1932 presidential election. A large caption reads, "Mit ihm" ("With him").

(Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-R99203 / CC-BY-SA 3.0 🔗.)

Die Bürgschaft is set in the imaginary land of Urb. The major characters are, on the one hand, the cattle dealer Johann Matthes, his wife Anna and daughter Luise, and on the other the grain dealer David Orth and his son Jakob. In the prologue, Matthes gambles away his money. Orth unhesitatingly pledges a guarantee on his friend's behalf. Act I takes place six years later. Matthes buys a sack of grain from Orth. Orth has deliberately hidden money in the sack, because he knows Matthes continues to have money problems. Matthes, first silent, tries to give the money back after being pressed by blackmailers. Orth won't take it. They agree to go to a judge. In Act II, the judge delivers a verdict straight out of Herder: their children will marry and receive the money. However, Ellis, soon to take Urb by force, changes the verdict, imprisons both Matthes and Orth, and confiscates the money (following Herder's Alexander). Anna discovers that their daughter Luise has disappeared. In Act III, six further years on Urb, under Ellis, has a wrecked economy; Matthes and Orth are out of prison, and each is experiencing some degree of prosperity. The chorus tells a story of war and deprivation. Matthes's wife Anna dies. A mob attacks Matthes as "guilty of betrayal." Matthes flees to Orth's house but "the world has changed" and Orth hands Matthes to the mob, who kill him.

Throughout this, the chorus repeatedly underlines the Marxist message that it is circumstances, not people, that change, and that "everything follows the law of money, the law of power." Ellis was clearly a surrogate for the Nazis, who responded with invective and threats, making it difficult to get the piece staged. Carl Ebert, director of Berlin's Städische Oper Charlottenberg (now the Deutsche Oper Berlin), refused to be intimidated; presumably that is what cost him his job when the Nazis take over, though he may well have chosen to leave in any case (in the event, he went to England and founded the Glyndebourne Festival Opera). Fritz Stiedry conducted the piece; Ebert directed; Weill and Neher did not simply hand over the finished libretto and score, but were active in rehearsals. The premiere on 10 March 1932 was a success, with Weill's mix of the classic and comtemporary meeting his usual high standard,and Neher's text, while no masterpiece, seen as a competent first time out as a librettist.

But it was 1932 in Germany. Six million people were out of work, and the Nazi party was increasingly in the ascendant. For the moment the institutions of the Weimar Republic held, but increasingly power was being contested mainly between the center-right and the far right, and the latter were ever more ready to resort to small-scale violence. While Weill and Neher had contracts to put on Die Bürgschaft in Hamburg, Coburg, Köonigsberg, Duisburg, Stettin, and Leipzig, all of these were cancelled in the face of right-wing threats and pressure. The only productions other than Berlin were in Düsseldorf (with Walter Bruno Iltz directing and Jascha Horenstein conducting) and Wiesbaden (with Paul Bekker directing and Karl Rankl conducting). Iltz was later to be perhaps the only significant collaborator of Weill's to weather the rise of Nazism more or less successfully and continue to work in Germany. First in Berlin and later at the Volkstheater in Vienna, Iltz somehow navigated the line of continuing to work in a responsible position in Nazi Germany without completely towing the party line, even occasionally managing to sneak some satire of the regime into his productions. (Caspar Neher also managed to stay in Germany and to continue to work in theater, but had a generally rougher time of it.) There seems to be remarkably little written about Iltz in English; here's his German-language Wikipedia article 🔗.

Fortunately for Weill, at least in the near term, Threepenny Opera and numerous of his songs continued to be enormously popular, providing a steady income (as did Lenya's increasing stardom as a performer). A bit too confident that the the Weimar Republic could keep the Nazis in check, and a bit too confident that their marriage would hold together, the pair acquired a house in Kleinmachnow, a suburb about half an hour from Berlin and then popular with people in the arts. Needless to say, a mere year later it would not be terribly convenient for Weill to be an ethnic Jew with a good deal of his net worth tied up on real estate in Germany. In that brief interval, he would manage one more major collaboration with Georg Kaiser; stay tuned.

[This essay draws heavily on Jürgen Schebera's meticulously researched Kurt Weill: an illustrated life, (Yale, 1995, translated from the original German by Caroline Murphy). Most of the information about Der Neinsager is drawn from Ronald Hayman's biography Brecht (1983, Oxford University Press).]

Next blog post: Standing on the Verge

Next Weill biography blog post: Standing on the Verge