By date

- 8 March 2021: Welcome!

- 9 March 2021: Kurt Weill and John Cale

- 18 March 2021: Happy Birthday, Kurt Weill!

- 26 March 2021: Working on "Mussel From Margate" and "Jealousy Duet"

- 03 April 2021: The Young Kurt Weill in Dessau

- 16 April 2021: Weill's Student years (1)

- 26 April 2021: Face-to-face!

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 20 May 2021: Novembergruppe

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 28 June 2021: Schickelgruber (song)

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 12 July 2021: What Is 'Epic Theater'?

- 15 July 2021: What Keeps Mankind Alive? (song)

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 25 July 2021: Speak Low (song)

- 2 August 2021: Youkali (song)

- 9 August 2021: François Villon

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 23 August 2021: Not exactly a manifesto

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 18 October 2021: Kurt Weill and shadow puppetry

- 25 October 2021: Summer 1933

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 8 November 2021: The Eternal Road

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 13 December 2021: One Touch of Venus

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 3 January 2022: Jewish Kurt Weill

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- 28 February 2022: Down in the Valley

- 14 March 2022: Love Life

- 28 March 2022: Lost in the Stars

Kurt Weill biography

- 03 April 2021: The Young Kurt Weill in Dessau

- 16 April 2021: Weill's Student years (1)

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 25 October 2021: Summer 1933

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 8 November 2021: The Eternal Road

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 13 December 2021: One Touch of Venus

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 3 January 2022: Jewish Kurt Weill

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- 28 February 2022: Down in the Valley

- 14 March 2022: Love Life

- 28 March 2022: Lost in the Stars

Lotte Lenya biography

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

By topic

- Agnes de Mille

- Alabama Song

- Alan Jay Lerner

- Alan Paton

- Arnold Sundgaard

- Baden-Baden

- Ben Hecht

- Berlin

- 16 April 2021: Weill's Student years (1)

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 20 May 2021: Novembergruppe

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- Berlin Im Licht

- Berliner Requiem

- Bertolt Brecht

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 12 July 2021: What Is 'Epic Theater'?

- 15 July 2021: What Keeps Mankind Alive? (song)

- 9 August 2021: François Villon

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- Broadway opera

- Caspar Neher

- Charles Lindbergh

- Complainte de la Seine

- Danny Kaye

- Darren Loucas

- David Drew

- Der Neinsager

- Der Protagonist

- Die Bürgschaft

- Down in the Valley

- Dresden

- East Portland Blog

- Elia Kazan

- Elisabeth Hauptmann

- Elmer Rice

- Engelbert Humperdinck

- Epic theater

- Erika Neher

- Erwin Piscator

- Eternal Road

- Expressionism

- Felix Jackson

- Firebrand of Florence

- Franz Werfel

- Frauentanz

- Fritz Busch

- Georg Kaiser

- George Antheil

- Georges Rouault

- Gertrude Lawrence

- Hannah Höch

- Hans Curjel

- Hollywood

- Hyperinflation

- Ira Gershwin

- Ivan Goll

- Jealousy Duet

- Jean Cocteau

- Jewish Kurt Weill

- Joe Mabel

- 8 March 2021: Welcome!

- 9 March 2021: Kurt Weill and John Cale

- 26 March 2021: Working on "Mussel From Margate" and "Jealousy Duet"

- 16 April 2021: Weill's Student years (1)

- 26 April 2021: Face-to-face!

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 20 May 2021: Novembergruppe

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 28 June 2021: Schickelgruber (song)

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 12 July 2021: What Is 'Epic Theater'?

- 15 July 2021: What Keeps Mankind Alive? (song)

- 25 July 2021: Speak Low (song)

- 2 August 2021: Youkali (song)

- 9 August 2021: François Villon

- 23 August 2021: Not exactly a manifesto

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 25 October 2021: Summer 1933

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 8 November 2021: The Eternal Road

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 13 December 2021: One Touch of Venus

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 3 January 2022: Jewish Kurt Weill

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- 28 February 2022: Down in the Valley

- 14 March 2022: Love Life

- 28 March 2022: Lost in the Stars

- Johann Gottfried Herder

- John Cale

- Juliana Brandon

- 8 March 2021: Welcome!

- 18 March 2021: Happy Birthday, Kurt Weill!

- 26 March 2021: Working on "Mussel From Margate" and "Jealousy Duet"

- 26 April 2021: Face-to-face!

- 28 June 2021: Schickelgruber (song)

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 25 July 2021: Speak Low (song)

- 2 August 2021: Youkali (song)

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 23 August 2021: Not exactly a manifesto

- 18 October 2021: Kurt Weill and shadow puppetry

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

- Kuhhandel

- Kurt Weill

- 8 March 2021: Welcome!

- 9 March 2021: Kurt Weill and John Cale

- 18 March 2021: Happy Birthday, Kurt Weill!

- 26 March 2021: Working on "Mussel From Margate" and "Jealousy Duet"

- 03 April 2021: The Young Kurt Weill in Dessau

- 16 April 2021: Weill's Student years (1)

- 26 April 2021: Face-to-face!

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 20 May 2021: Novembergruppe

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 28 June 2021: Schickelgruber (song)

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 12 July 2021: What Is 'Epic Theater'?

- 15 July 2021: What Keeps Mankind Alive? (song)

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 25 July 2021: Speak Low (song)

- 2 August 2021: Youkali (song)

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 23 August 2021: Not exactly a manifesto

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 18 October 2021: Kurt Weill and shadow puppetry

- 25 October 2021: Summer 1933

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 8 November 2021: The Eternal Road

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 13 December 2021: One Touch of Venus

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 3 January 2022: Jewish Kurt Weill

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- 28 February 2022: Down in the Valley

- 14 March 2022: Love Life

- 28 March 2022: Lost in the Stars

- Léo Lania

- Lüdenscheid

- Lady in the Dark

- Langston Hughes

- Lost in the Stars

- Lotte Lenya

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- Lotte Reiniger

- Love Life

- Lys Symonette

- Mahagonny

- Man Without Qualities

- Marc Blitzstein

- Marlene Dietrich

- Mary Martin

- Maurice Abravanel

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- Max Reinhardt

- Maxwell Anderson

- Meyer Weisgal

- Moss Hart

- Mussel From Margate

- Nazizeit

- New York

- One Touch of Venus

- Otto Dix

- Otto Pasetti

- Paris

- Princess du Polignac

- Robert Vambery

- Roger Fernay

- S.J. Perelman

- Scherenschnitte

- Schickelgruber

- Seven Deadly Sins

- Shadow puppetry

- Silbersee

- Street Scene

- Threepenny Opera

- Tilly Losch

- Weill Project

- 8 March 2021: Welcome!

- 9 March 2021: Kurt Weill and John Cale

- 18 March 2021: Happy Birthday, Kurt Weill!

- 26 March 2021: Working on "Mussel From Margate" and "Jealousy Duet"

- 26 April 2021: Face-to-face!

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 28 June 2021: Schickelgruber (song)

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 15 July 2021: What Keeps Mankind Alive? (song)

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 25 July 2021: Speak Low (song)

- 2 August 2021: Youkali (song)

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 23 August 2021: Not exactly a manifesto

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 18 October 2021: Kurt Weill and shadow puppetry

- 25 October 2021: Summer 1933

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 8 November 2021: The Eternal Road

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 13 December 2021: One Touch of Venus

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 3 January 2022: Jewish Kurt Weill

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- 28 February 2022: Down in the Valley

- 14 March 2022: Love Life

- 28 March 2022: Lost in the Stars

- Weill Project Blog

- Weill family

- Weill's Second Symphony

- What Keeps Mankind Alive

- What Was Sent to the Soldier's Wife

- World War II

- World War II propaganda

- Young Kurt Weill

- Yvette Endrijautzki

- Zeitoper

- degenerate art

Tags

#kurtweill # #newyork #worldwarii #nazizeit #bertoltbrecht #lottelenya #joemabel #weillproject #weillbio

(Prior biographical posts on Weill: [1],

[2],

[3],

[4],

[5],

[6],

[7],

[8],

[9],

[10],

[11],

[12],

[13],

[14],

[15],

[16],

[17],

[18],

[19],

[20],

[21].

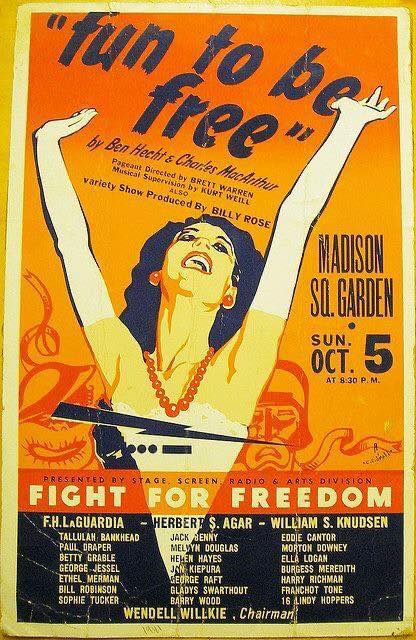

Poster for the "Fun to be Free" pageant at Madison Square Garden. Cast members included Tallulah Bankhead, Betty Grable, George Jessel, Ethel Merman, Jack Benny,

Burgesss Meredith, and "16 Lindy Hoppers".

Public domain

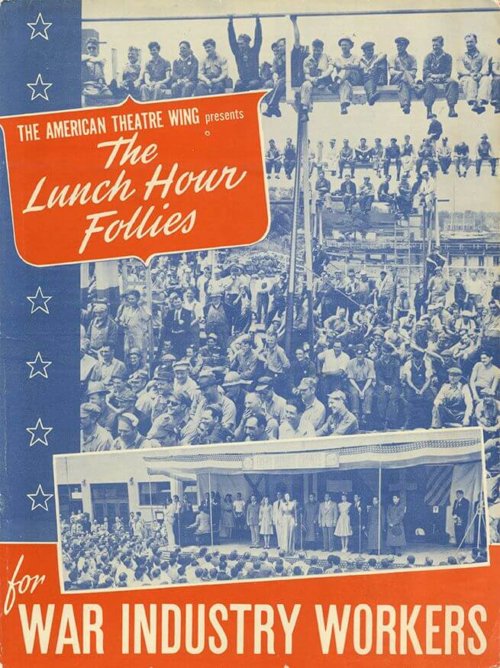

Somehow we've come down to 1943 and barely mentioned World War II. Lady in the Dark and One Touch of Venus were big commercial successes for Weill, but it looks to me like his life in those years may have been almost equally focused on what he could do for the war effort. Let's take a step back.

Weill himself left Germany in late March 1933, and after two years in France came to America as part of the team of the pageant play The Eternal Road. Most of his family left Germany soon after, and ended up also in relative safety in the British Mandate of Palestine. Unlike most of those who left Germany after the Nazi takeover, Weill quickly decided to focus his life on becoming an American. The contrast was strong: in 1944, he would write to Lenya after visiting with a number of emigré friends who had gone to Hollywood, that he was "[beginning to think] that we are almost the only ones of these people who have found American friends and who really live in this country. They are all still living in Europe." And he (and Lenya) had found American friends. Weill was working as a peer with the leading lights of New York theater, a sought-after composer who was one of few recent immigrants among the twenty or so people who defined the American musical as we know it. Since 1936, he had been attempting as much as possible to live his life in the English language, even in his correspondence with Lenya. Since at least 1941 he had defined himself as "an American" even though it would be two more years until he and Lenya were officially granted citizenship.

Of course, this did nothing to diminish his hatred of the Nazis and his concern to oppose them. Weill was an early member of the Fight For Freedom Committee, formed April 20, 1941 to urge the U.S. to enter the war as a belligerent on the Allied side. This was a direct confrontation of Charles Lindbergh's America First Committee. The Fight For Freedom Committee's manifesto called for "a willingness to do whatever is necessary" to defeat Hitler, and added, "This means accepting the fact that we are at war, whether declared or undeclared. Regardless of what we do, Hitler will attack us when he feels it to his advantage." Through Fight for Freedom, Weill became musical supervisor of the pageant play Fun to Be Free staged October 5, 1941 at Madison Square Garden, working with such luminaries as Ben Hecht, Charles MacArthur, and Billy Rose. Interestingly, despite Walt Disney's reputation for conservatism and even anti-Semitism, Disney artist Hank Porter was given permission to contribute a program cover featuring Mickey Mouse, Goofy, and Donald Duck.

Another effort of Weill's before Pearl Harbor went nowhere, though I'm not clear on exactly why. With Erika Mann 🔗 and Bruno Frank 🔗, he tried to form an organization of anti-Nazi "aliens". Both Mann and Frank were mainstays of the German exile community around the film industry in Los Angeles. Eldest child of author Thomas Mann, Erika Mann is quite an interesting figure in her own right. I can't do her justice in a brief paragraph, but I can say a bit. Shortly after the Reichstag Fire, she and her brother Klaus 🔗 left Bavaria, first for Switzerland and later for America. In Switzerland, Erica Mann formed a marriage of convenience with British poet W.H. Auden 🔗. Both Erika and Klaus Mann were gay, as was Auden, who was in a rather long-term relationship with Christopher Isherwood 🔗 at the time he legally married Erika. Among many other achievements in life, in exile Erika Mann became a war correspondent (Spanish Civil War and World War II) and with her brother Klaus wrote two rather important books attacking the Nazis: School for Barbarians (1938) on what the Nazis had done to education in Germany and Escape to Life (1939), a look at the German intellectual diaspora of the times that is certainly still worth reading today. Written in German but originally published only in English, the German-language version was finally published in 1991. Somehow, Erika Mann navigated life as a lesbian in the mid-twentieth century pretty successfully; her brother Klaus was much less fortunate. He struggled to find close relationships. He served in the U.S. military during the war and did manage to become a U.S. citizen despite suspicion of both his sexuality and his far-left politics, but ended up killing himself in 1949. Besides his collaborations with his sister, he is probably now best remembered for the novel Mephisto 🔗.

And then war. As we all know, on December 7, 1941 the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. The next day the U.S. declared war on the Axis Powers. Days later, on December 12, Weill proposed a "cultural attack" on Germany by shortwave radio. It would seem that his views were influential on the arts being seen as part of the Office of War Information, which eventually set up shortwave broadcasts intended to reach the German populace and later, after D-Day, similar longwave broadcasts from behind the front lines. And, in a matter that can be seen as entirely serious or entirely ludicrous, Weill and playwright Maxwell Anderson (see prior blog post) volunteered as air wardens and took shifts doing watches on a hill in suburban New City, New York, where Anderson had long lived, and where Weill bought a home in May 1941 thanks to the success of Lady in the Dark.

Unsurprisingly, Weill's main contribution to the war effort came as a composer, writing music for a variety of propaganda songs, ranging from eight songs for Moss Hart's 🔗 Lunchtime Follies (which ventured out to entertain workers in New York-area defense plants) to various fund-raising pageants to several songs intended specifically for targeted broadcast into Germany. I know some of this material well; others are little more than titles to me. Given that he also wrote several major musicals in these years (and was accused by Elia Kazan of micromanaging the production for one of them, it must have been an incredibly busy life. To be honest, I can barely keep some of the chronology straight here, but I'll try to at least hit the high points. Part of what interests me is the prodigious number of first-rate writers and performers with whom he collaborated.

In January 1942, Weill completed several pieces for actress Helen Hayes 🔗: orchestrations of "America", the "Star-Spangled Banner", and the "Battle Hymn of the Republic", but more notably, settings of several Walt Whitman poems: "Beat! Beat! Drums!", "O Captain! My Captain!", and "Dirge for Two Veterans". In 1947, he would also set Whitman's "Come Up from the Fields, Father"; the four Whitman songs are now usually performed together. The well-read Weill had probably already encountered Whitman before leaving Germany, but Whitman was a particular favorite of Paul Green's (his first major American collaborator, see prior blog post) and Green had given him a copy of Whitman's Leaves of Grass as a gift around the time of their collaboration on Johnny Johnson.

In February 1942, Weill wrote incidental music for Maxwell Anderson's one-act radio play Your Navy (a score that incorporated traditional sea shanties and war songs), and later that year set Archibald MacLeish's 🔗 "Song of the Free", which was used that June as a framework for a Flag Day broadcast. But it would seem that his biggest contribution along these lines in this period was to Moss Hart's abovementioned Lunchtime Follies. Weill wrote numerous songs for the troupe, and apparently often went out with them as something of a stage manager. Among Weill's Follies songs were "Shickelgruber", a satire on Hitler with lyrics by Howard Dietz 🔗. Hitler's father was born "Alois Shicklgruber" and only got the name "Hitler" after his mother married a man of that name. The song, which Juliana and I perform, presumably deliberately conflates the father and son ("You have always been a bastard even though you changed your name"). I wrote about the song back in June 2021 when we were first learning it. I've added a recent YouTube video to that page, for those who want to hear it.

Dorothy Fields 🔗 may not be a household name, but she should be: she was the lyricist for "I Can't Give You Anything But Love", "The Way You Look Tonight", "A Fine Romance", "On the Sunny Side of the Street", "I'm in the Mood for Love", and "Big Spender", and many others. I believe this was her only song with Weill, though.

Public domain

Other songs for the Follies included:

- "Buddy on the Night Shift" and "The Good Earth", lyrics by Oscar Hammerstein II 🔗 of Rogers & Hammerstein fame.

- "Inventory", lyrics by the pseudonymous Lewis Allan, actually Abel Meeropol 🔗, who would later write the anti-lynching song "Strange Fruit" and who, with his wife, would adopt the two sons of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg 🔗 after the latter couple were executed for espionage, almost certainly a frame-up in her case and possibly a partial frame-up in his.

- "One Morning in Spring", lyrics by New Yorker editor St. Clair McKelway 🔗

- "We Don't Feel Like Surrendering Today" and "Oh Uncle Samuel!", lyrics by Weill's frequent collaborator and fellow air warden Maxwell Anderson. In the latter, Weill reworked a melody by 19th-century American songwriter Henry Clay Work 🔗, who is probably better remembered for "My Grandfather's Clock" and "Marching Through Georgia". (Aside: Henry Clay Work was born in Middletown, Connecticut, where I went to college at Wesleyan University. There's a memorial to him in Hubbard Park near the north end of Middletown's Main Street shopping district.)

- "Toughen Up, Buckle Down, Carry On", lyrics by Dorothy Fields 🔗 (see picture and caption at right).

Weill Project collaborator Yvette Endrijautzki's 2021 placard for the song "Schickelgruber" envisions an aerial literature drop of sheet music.

Copyright Yvette Endrijautzki, all rights reserved.

Of those I've only heard "Buddy on the Nightshift" (recorded several times) and seen sheet music for that and "Inventory". I imagine most of these are out there somewhere in some form. I'll admit Lunchtime Follise isn't something I've particularly researched; I probably looked into it more just now for this blog entry than I ever have before.

A similar musical undertaking led to a sort of theme song for Russian War Relief. The lyrics were by another interesting New York character, author J.P. McEvoy 🔗, a frequent contributor to such popular magazines as the Saturday Evening Post and later Readers' Digest, and originator of the Dixie Dugan comic strip, who had also been one of the writers for the Ziegfeld Follies and whose sketches helped form the stage persona of W.C. Fields. The song was premiered August 1942 by Weill's wife Lotte Lenya, with Weill on piano, at a benefit concert in Rockland County, New York. I actually found a pretty cool article online about that concert 🔗. It sounds like it was quite a show: besides Weill and Lenya, it featured Helen Hayes, Ed Wynn, and Will Geer.

On another front, the war led to increased connection between Weill and the German exile community, including something of a rapprochement with Bertolt Brecht. Weill and Lenya got together with Brecht in Hollywood in October 1942, the first time they had met face to face since 1935. Lenya apparently sang Weill's 1939 setting of Brecht's "Nannas Lied," which Brecht really liked. Over then next year or so they made a few efforts to collaborate, and in May 1943 Brecht even came to New York for a working week together, but not much came of it. Jürgen Schebera is doubtless correct to write that "their artistic conceptions differed too much by now." Brecht ended up collaborating on most of these projects with Hanns Eisler 🔗. Weill apparently made some musical contributions to their Schweik in the Second World War 🔗, but I haven't worked out exactly what; the piece was not performed in Weill's lifetime, in any case.

Still, Brecht loved Lenya's evolving direction. When she worried aloud that her current approach might not be in line with Brecht's views on "epic theater", he assured her that anything she did was epic enough for him. In any case, Brecht ran several poems past Weill as possible songs, and while most of these eventually were taken up by Eisler, Weill did set one of them—the "Ballad of the Soldier's Wife"—and it certainly stands with anything else that the two wrote together. The song tells the story of the wife of a German soldier who, through most of the verses, receives souvenir gifts sent home from her husband as the Germans advance through Europe: a little Dutch hat, a silken gown, a Romanian skirt. Weill's music moves on, neither heavy nor light, but suggesting a steady progress. Then the tone turns funereal in the final verse. What is sent to her from Russia? A widow's veil. Lenya recorded the song in 1943 in the original German as "Und was bekam die Soldaten Weib", along with another Brecht war poem "Lied einer deutschen Muttter" ("Song of a German Mother") set to music by Paul Dessau, another prominent German composer who had escaped to the U.S. Both of these were used as propaganda in shortwave broadcasts into Germany. Among the many others who have recorded the "Ballad of the Soldier's Wife" are Marianne Faithfull (it was the first Weill song she recorded) and P.J. Harvey. Here's Marianne Faithfull performing it with Chris Spedding. 🔗

Weill provided the music for Ben Hecht's pageant play We Will Never Die 🔗, an effort to call public attention to the plight of Europe's Jews. It premiered March 9, 1943 at New York's Madison Square Garden, shortly before Weill plunged into the major work on bringing One Touch of Venus to the stage. I'm going to lay We Will Never Die aside for the moment, though, because it was the first of a series of specifically Jewish projects for Weill, the rest of them after the war ended, and I think those are better taken up together in a future post.

Meanwhile, Weill and Lenya performed together April 3, 1943 in We Fight Back, a revue at New York's Hunter College organized by Ernst Josef Aufricht and Manfred George 🔗. You may remember Aufricht as the actor who, in 1928, took a multi-year lease on Berlin's Theater am Schiffbauerdamm, and his encounter with Brecht that led to Threepenny Opera. Manfred George, born Manfred Georg Cohn, was an ethnically Jewish German journalist. By this time, he was editor of Aufbau, a German-language publication that was originally the monthly newsletter of the German Jewish Club of New York (now the New World Club), which George built into an influential weekly with a circulation of 30,000. I haven't been able to find out much about the Hunter College event, other than that "Und was bekam die Soldaten Weib" went over particularly well.

Weill wrote quite a few other songs for the war effort, many of them highly praised at the time, but from what I gather a lot of them are lost, such as work for the Entertainment Section of the U.S. Army on a Soldier Shows production called Three Day Pass. At least one other 1944 song written for broadcast into Germany does survive: "Wie lange noch?", lyrics by Walter Mehring 🔗 (best known as a satirist, and at this time also writing for Aufbau), and sung once again by Lenya. Here's a slightly static-y version of their recording. 🔗 The melody is a self-plagiarism from Weill's setting of Maurice Magre's "Je ne t'aime pas", written during Weill's earlier Parisian exile. In Mehring's lyric, the female singer sings to an ex-lover, holding him to account for broken promises. It is a thinly-veiled allegory of the Germans, betrayed by the Nazis.

Also in 1944, Weill wrote adaptations of French songs (and Maxwell Anderson wrote a script) for Jean Renoir's 🔗 semi-documentary film Salute to France. And with Ira Gershwin, as sort of a warmup to Firebrand of Florence, he wrote songs for the film Where Do We Go From Here?, probably Weill's "least bad" experience with the American film industry, but which had the misfortune to be a military time-travel fantasia that came out after World War II had ended. Not that anyone could be unhappy World War II had ended. We'll take up Where Do We Go From Here? in an upcoming blog post about Firebrand of Florence.

[This essay draws heavily on Jürgen Schebera's meticulously researched Kurt Weill: an illustrated life, (Yale, 1995, translated from the original German by Caroline Murphy).]

Next blog post: Jewish Kurt Weill

Next Weill biography blog post: Jewish Kurt Weill