By date

- 8 March 2021: Welcome!

- 9 March 2021: Kurt Weill and John Cale

- 18 March 2021: Happy Birthday, Kurt Weill!

- 26 March 2021: Working on "Mussel From Margate" and "Jealousy Duet"

- 03 April 2021: The Young Kurt Weill in Dessau

- 16 April 2021: Weill's Student years (1)

- 26 April 2021: Face-to-face!

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 20 May 2021: Novembergruppe

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 28 June 2021: Schickelgruber (song)

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 12 July 2021: What Is 'Epic Theater'?

- 15 July 2021: What Keeps Mankind Alive? (song)

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 25 July 2021: Speak Low (song)

- 2 August 2021: Youkali (song)

- 9 August 2021: François Villon

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 23 August 2021: Not exactly a manifesto

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 18 October 2021: Kurt Weill and shadow puppetry

- 25 October 2021: Summer 1933

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 8 November 2021: The Eternal Road

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 13 December 2021: One Touch of Venus

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 3 January 2022: Jewish Kurt Weill

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- 28 February 2022: Down in the Valley

- 14 March 2022: Love Life

- 28 March 2022: Lost in the Stars

Kurt Weill biography

- 03 April 2021: The Young Kurt Weill in Dessau

- 16 April 2021: Weill's Student years (1)

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 25 October 2021: Summer 1933

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 8 November 2021: The Eternal Road

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 13 December 2021: One Touch of Venus

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 3 January 2022: Jewish Kurt Weill

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- 28 February 2022: Down in the Valley

- 14 March 2022: Love Life

- 28 March 2022: Lost in the Stars

Lotte Lenya biography

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

By topic

- Agnes de Mille

- Alabama Song

- Alan Jay Lerner

- Alan Paton

- Arnold Sundgaard

- Baden-Baden

- Ben Hecht

- Berlin

- 16 April 2021: Weill's Student years (1)

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 20 May 2021: Novembergruppe

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- Berlin Im Licht

- Berliner Requiem

- Bertolt Brecht

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 12 July 2021: What Is 'Epic Theater'?

- 15 July 2021: What Keeps Mankind Alive? (song)

- 9 August 2021: François Villon

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- Broadway opera

- Caspar Neher

- Charles Lindbergh

- Complainte de la Seine

- Danny Kaye

- Darren Loucas

- David Drew

- Der Neinsager

- Der Protagonist

- Die Bürgschaft

- Down in the Valley

- Dresden

- East Portland Blog

- Elia Kazan

- Elisabeth Hauptmann

- Elmer Rice

- Engelbert Humperdinck

- Epic theater

- Erika Neher

- Erwin Piscator

- Eternal Road

- Expressionism

- Felix Jackson

- Firebrand of Florence

- Franz Werfel

- Frauentanz

- Fritz Busch

- Georg Kaiser

- George Antheil

- Georges Rouault

- Gertrude Lawrence

- Hannah Höch

- Hans Curjel

- Hollywood

- Hyperinflation

- Ira Gershwin

- Ivan Goll

- Jealousy Duet

- Jean Cocteau

- Jewish Kurt Weill

- Joe Mabel

- 8 March 2021: Welcome!

- 9 March 2021: Kurt Weill and John Cale

- 26 March 2021: Working on "Mussel From Margate" and "Jealousy Duet"

- 16 April 2021: Weill's Student years (1)

- 26 April 2021: Face-to-face!

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 20 May 2021: Novembergruppe

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 28 June 2021: Schickelgruber (song)

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 12 July 2021: What Is 'Epic Theater'?

- 15 July 2021: What Keeps Mankind Alive? (song)

- 25 July 2021: Speak Low (song)

- 2 August 2021: Youkali (song)

- 9 August 2021: François Villon

- 23 August 2021: Not exactly a manifesto

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 25 October 2021: Summer 1933

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 8 November 2021: The Eternal Road

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 13 December 2021: One Touch of Venus

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 3 January 2022: Jewish Kurt Weill

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- 28 February 2022: Down in the Valley

- 14 March 2022: Love Life

- 28 March 2022: Lost in the Stars

- Johann Gottfried Herder

- John Cale

- Juliana Brandon

- 8 March 2021: Welcome!

- 18 March 2021: Happy Birthday, Kurt Weill!

- 26 March 2021: Working on "Mussel From Margate" and "Jealousy Duet"

- 26 April 2021: Face-to-face!

- 28 June 2021: Schickelgruber (song)

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 25 July 2021: Speak Low (song)

- 2 August 2021: Youkali (song)

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 23 August 2021: Not exactly a manifesto

- 18 October 2021: Kurt Weill and shadow puppetry

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

- Kuhhandel

- Kurt Weill

- 8 March 2021: Welcome!

- 9 March 2021: Kurt Weill and John Cale

- 18 March 2021: Happy Birthday, Kurt Weill!

- 26 March 2021: Working on "Mussel From Margate" and "Jealousy Duet"

- 03 April 2021: The Young Kurt Weill in Dessau

- 16 April 2021: Weill's Student years (1)

- 26 April 2021: Face-to-face!

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 20 May 2021: Novembergruppe

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 28 June 2021: Schickelgruber (song)

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 12 July 2021: What Is 'Epic Theater'?

- 15 July 2021: What Keeps Mankind Alive? (song)

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 25 July 2021: Speak Low (song)

- 2 August 2021: Youkali (song)

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 23 August 2021: Not exactly a manifesto

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 18 October 2021: Kurt Weill and shadow puppetry

- 25 October 2021: Summer 1933

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 8 November 2021: The Eternal Road

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 13 December 2021: One Touch of Venus

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 3 January 2022: Jewish Kurt Weill

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- 28 February 2022: Down in the Valley

- 14 March 2022: Love Life

- 28 March 2022: Lost in the Stars

- Léo Lania

- Lüdenscheid

- Lady in the Dark

- Langston Hughes

- Lost in the Stars

- Lotte Lenya

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- Lotte Reiniger

- Love Life

- Lys Symonette

- Mahagonny

- Man Without Qualities

- Marc Blitzstein

- Marlene Dietrich

- Mary Martin

- Maurice Abravanel

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- Max Reinhardt

- Maxwell Anderson

- Meyer Weisgal

- Moss Hart

- Mussel From Margate

- Nazizeit

- New York

- One Touch of Venus

- Otto Dix

- Otto Pasetti

- Paris

- Princess du Polignac

- Robert Vambery

- Roger Fernay

- S.J. Perelman

- Scherenschnitte

- Schickelgruber

- Seven Deadly Sins

- Shadow puppetry

- Silbersee

- Street Scene

- Threepenny Opera

- Tilly Losch

- Weill Project

- 8 March 2021: Welcome!

- 9 March 2021: Kurt Weill and John Cale

- 18 March 2021: Happy Birthday, Kurt Weill!

- 26 March 2021: Working on "Mussel From Margate" and "Jealousy Duet"

- 26 April 2021: Face-to-face!

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 28 June 2021: Schickelgruber (song)

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 15 July 2021: What Keeps Mankind Alive? (song)

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 25 July 2021: Speak Low (song)

- 2 August 2021: Youkali (song)

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 23 August 2021: Not exactly a manifesto

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 18 October 2021: Kurt Weill and shadow puppetry

- 25 October 2021: Summer 1933

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 8 November 2021: The Eternal Road

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 13 December 2021: One Touch of Venus

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 3 January 2022: Jewish Kurt Weill

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- 28 February 2022: Down in the Valley

- 14 March 2022: Love Life

- 28 March 2022: Lost in the Stars

- Weill Project Blog

- Weill family

- Weill's Second Symphony

- What Keeps Mankind Alive

- What Was Sent to the Soldier's Wife

- World War II

- World War II propaganda

- Young Kurt Weill

- Yvette Endrijautzki

- Zeitoper

- degenerate art

Tags

#kurtweill #bertoltbrecht #elisabethhauptmann #lottelenya #joemabel #weillproject #berlin #berlinimlicht #musselfrommargate #berlinerrequiem #charleslindbergh #happyend #weillbio(Prior biographical posts on Weill: [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7] [8]. Also, see this post on the Novembergruppe.)

We left off a few weeks ago at a moment of triumph for Weill, Brecht, and the often uncredited Elisabeth Hauptmann 🔗 in 1928: their Dreigroschenoper ("Threepenny Opera") was breaking all records at the Theater am Schiffbauerdamm and productions were being launched throughout the German-speaking world. Songs from the play (and a few earlier songs along similar lines) were being re-arranged for jazz orchestra, salon orchestra, vocal and piano, violin and piano, recorded by a variety of artists, and played on bandstands in Germany and beyond. As icing on the cake, only six weeks later Weill's fox-trot theme song for the Berlin Im Licht festival was another hit, and the role of Jenny in Dreigroschenoper made Weill's wife Lotte Lenya a star: in the next year she appeared on stage in major roles such as Ismene in Sophocles' Oedipus and Ilse in Frank Wedekind's Spring Awakening. Beyond the personal: the Weimar Republic looked, for the moment, like a success, and Berlin was overmatching Paris as the cutting-edge cultural center of Europe.

We haven't yet recorded our version of Weill's "Berlin Im Licht Song", so for now you'll have to, uh, settle for the Berlin Staatsoper. YouTube won't let us embed this, but click through and enjoy listening to pianist Daniel Barenboim drive HK Gruber and the Berlin Staatsoper orchestra through a manic version of "Berlin Im Licht", New Years 1997. Gruber, the vocalist here, is best known as a composer and conductor, but as a child he was in the Vienna Boys Choir. I'm guessing that (1) he's sight-singing (no rehearsal) and (2) he'd had a few drinks by that point in the evening.

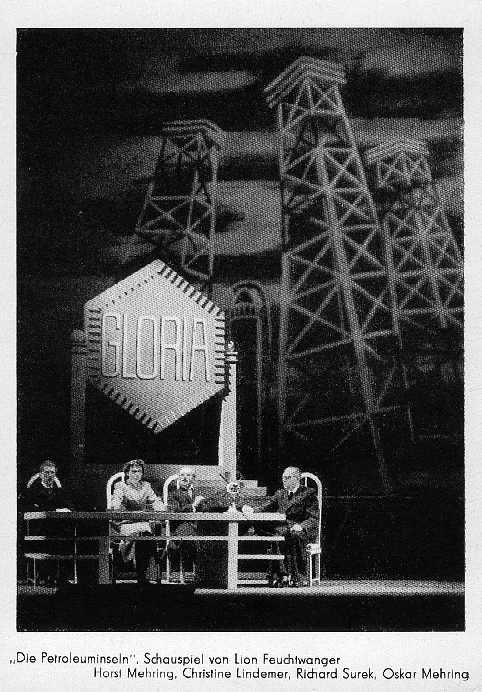

Weill, having written incidental music and a few songs for Leo Lania's anti-corporate environmentalist play Konjuntur early in 1928, did the same for a major production of Lion Feuchtwanger's 1923 Die Petroleuminseln, which opened 28 Nov 1928 at the Staatliches Schauspielhaus am Gendarmenmarkt, with Lenya as Charmian Peruchacha singing Weill and Feuchtwanger's "Das Lied der braunen Inseln" ("Song of the Brown Islands"), a rather surreal song in which a sexually voracious female ape rules over an environmental wasteland. The song is excellent, but was not a hit, and seems to have been largely forgotten until Teresa Stratas recorded it in 1981. (We perform both "Das Lied der braunen Inseln" and "Mussel from Margate," a song from Konjuntur about the Shell Oil Company. Probably two of the earliest environmental protest songs ever written.)

Meanwhile, Brecht and Weill embarked on what was originally seen as one broad project commissioned by Reichs-Rundfunk-Gesellschaft, Germany's massive public radio network. Instead of a single massive piece, it eventually became three major pieces—the Brecht/Weill Berliner Requiem and Der Lindberghflug ("The Lindbergh Flight"), as well as Das Badener Lehrstück ("The Baden Teaching-Piece"), which Brecht wrote with Paul Hindemith—plus a few songs that didn't make it into any of these larger works.

The Berliner Requiem went through several versions. In all of them, this anti-war "secular requiem" clearly memorialized in particular the Communist martyr Rosa Luxemburg, then only ten years dead, whose blood was quite arguably on the hands of the Social Democrats, the party that headed Germany's governing coalition at the time the Requiem was written. Even at the height of this left-liberal regime, the most progressive of the Weimar era, memorializing Rosa Luxemburg pushed the limits of what could get on the radio. It was broadcast only once, 22 May 1929, and only in Frankfurt. The network refused to broadcast it in Berlin, and as a result Weill quit his side job writing for the network's magazine Der deutsche Rundfunk. (By the way, one of the few songs Weill ever explicitly wrote for guitar is the "Ballad of the Drowned Girl" from Berliner Requiem.)

One song—"Legende vom toten Soldaten" ("Legend of the Dead Soldier")—didn't make it into Berliner Requiem. Instead, it was separately performed in November 1929 by Berlin's Schubert-Choir, who also performed "Zu Potsdam unter den Eichen" ("To Potsdam Under the Oaks"), one of the songs that did make it in. "Potsdam" tells the story of a peace march that gradually gathers energy and hope but is ultimately stopped short by the police; the far darker "Legend of the Dead Soldier" is about a dead soldier who is reanimated only to go obediently back into battle and die again. Both songs are satiric. "Legend of the Dead Soldier" reworks a poem Brecht wrote while World War I was still raging, and is among the most bitter lyrics that Brecht ever wrote, which is saying a lot. The structure of the poem is a bit tricky: not only is it not end-stopped 🔗, but it often breaks a single word across two lines. Weill was not the first to set it to music: Brecht himself sometimes sang a simple version in cabarets in the 1920s. I don't think there is a recording of Brecht singing it, but here are YouTube links for recordings by Ernst Busch and by Dave Van Ronk 🔗, both using Brecht's version. I've known the Van Ronk cover for about 30 years; only in the course of research for this current project did I find out about Weill's very different setting. Apparently Hanns Eisler also set it at some point, though his version is lost. Weill wrote a discordant choir version 🔗 that gives Brecht's text an angular, sometimes marching, sometimes limping, 6/8 tempo that fits the poetic structure and the macabre lyrics.

As you may remember Weill and Brecht had scored a big success at the 1927 Baden-Baden Festival with the Mahagonny Songspiel. The theme for the 1929 Baden-Baden Festival was film and radio, and both Der Lindberghflug and Das Badener Lehrstück were written for that festival. I won't dwell here on Das Badener Lehrstück, since Weill was not involved in it, but Der Lindberghflug was such a major undertaking that in order to have it done in time Weill and Hindemith divided the musical duties. That was very appropriate to the theme of the piece, which views Lindbergh's solo flight as more of a collective achievement (the aircraft designers, the mechanics, the radio operators), while also engaging phenomena of weather and of the atmosphere as a space. Following Brecht's conception, the piece was staged as if it were being broadcast from a radio studio, with one performer at stage left impersonating a radio listener, humming along at times and so forth (though apparently this pretty much went right past the audience and critics).

Once again, they found themselves with the biggest hit of the festival, despite the contrast between what critic Heinrich Strobel called "Weill's songlike, clearly declamatory composition" and Hindemith's "more descriptive, heavy music." The "radio" aspect of the piece came full circle when the Berlin Philharmonic did a broadcast performance in March 1930; they also recorded it. The score of this version of Der Lindberghflug is published in Hindemith's collective works.

Weill was never satisfied with this two-headed musical beast and decided he would write his own settings for Hindemith's parts. The result was a 15-part cantata with what Jürgen Schebera characterizes as "simple musical language" and "dialogs between aviator and chorus." Weill had hoped the work could be performed by amateurs, but it was a bit too difficult. It premiered 5 Dec 1929 at the Krolloper in Berlin, on a bill with pieces by Stravinsky and Hindemith. Otto Klemperer directed the Preußische Staatskapelle, Erik Wirl sang the role of Lindbergh, and Karl Rankl prepared the choir. Reviews were mixed, with the conservative press uniformly negative. Both sides noted the simplicity of the music, but placed different values on that. Erich Urban wrote in the Berliner Zeitung, "I like this piece because it gives an artistic formulation of contemporary events, because the combining of voice and speech, the voice distribution, the conversations between people, nature, and things are unusual. Weill took care of this with his means; it has a lot going for it. The introduction of the aviator Lindbergh, the conversations with fog, snow storm, and engine, the lullaby (an enchanting blues song), the ghostlike fishers, and the apotheosis. Erik Wirl as Lindbergh is outstanding. Opera–operetta–opera."

The piece was published in 1930 by Weill's usual publisher, Universal Edition, in a piano reduction with a bilingual score: American composer George Antheil—a colleague of Brecht, Weill, and Hindemith from the Novembergruppe—had translated Brecht's libretto into English. On 4 April 1931, Leopold Stokowski and the Philadelphia Orchestra gave the piece its American premiere. Weill sent Lindbergh a copy of the published work "with great admiration" but of course Lindbergh's later drift into right-wing politics eventually resulted in a revision of that opinion. Lindbergh didn't quite become a Nazi, but neither did Henry Ford. Brecht officially renamed the piece Der Ozeanflug ("The Ocean Flight") and removed all references to Lindbergh from the text.

The time required to complete these pieces is doubtless part of the reason that the next Brecht/Weill Berlin theater piece, Happy End (the title was always in English) was a rather slap-dash affair. Threepenny Opera played to sold-out houses at the Theater am Schiffbauerdamm for the entire 1928-1929 season, but the theater traditions of the time made it unthinkable simply to hold it over into the next season. (Stephen Hinton seems to indicate that essentially the same production did continue somewhere in Berlin into the next season, but obviously not at the Schiffbauerdamm, where Happy End took over the stage. If anyone has more details, they'd be greatly appreciated. - JM) Ernst Josef Aufricht, who operated the theater, brought together pretty much the same team for Happy End as for Threepenny, but Brecht had basically nothing in progress by way of a plot. The resulting play was attributed to a certainly fictitious "Dorothy Lane"; there is some question as to whether Brecht or Weill had even a hand in anything but the songs. Weill biographer Jürgen Schebera seems confident that aside from the songs the script was entirely Elisabeth Hauptmann's.

Compounding any lack of focus on Brecht's part: Brecht and Weill intended to spend May 1929 on the Riviera to hammer out the script and songs. [Or maybe just songs. According to Stephen Hinton, Brecht had written a few notes on plot and handed them off to Elisabeth Hauptmann, with the intention all along being that she would write the bulk of the play.] Brecht, driving from Berlin in the car he bought with the money from last year's hits, had an auto accident en route and broke his kneecap. Weill had to take him home to Berlin. Under the circumstances, it's pretty amazing that Brecht managed even song lyrics, but that July Brecht and Weill settled in at Brecht's house in Unteschondorf am Ammersee, wrote like mad, and had a full score ready for orchestra rehearsal 25 August. [Again a corrective, via Hinton. He follows Paula Hannsen in her 1995 book Elisabeth Hauptmann: Brecht's Silent Collaborator in believing that Hauptmann actually wrote about half the song lyrics in the play: the bulk of the Salvation Army songs plus "Das Lied von der harten Nuß". Hinton points out that the Salvation Army songs are much more integral to the plot than the others, because music is the main tool through which the Salvation Army within the play attempts to convert people. All of these song lyrics that Hannsen and Hinton think were Hauptmann's were unpublished until the 1970s, and when they were it was under Hauptmann's copyright.]

Peter Lorre, 1946. Like Weill, Lenya and many others of their circle, after the rise of the Nazis Lorre emigrated to the U.S. and became an American citizen.

The plot is so thin that Happy End was really little more than a revue: gangsters, Salvation Army girl, safe-cracking, guns, conversions. Imagine Guys and Dolls without either the trip to Havana or the Nathan/Adelaide subplot that gives that play some oomph. But the songs are as good as any that the pair ever wrote. Six "Salvation Army songs" parody conventional religious inspirational music. The other six songs are sung in a disreputable bar known as Bills Ballhaus and, honestly, none of them move the plot forward an inch and most don't even relate much to the characters who sing them. Often as not, all the relation the song has to the plot is that someone says something like, "Hey, would you sing that Bilbao Song?" Besides the "Bilbao-Song," Happy End includes the first version of "Mandelay," the "Matrosen-Song" ("The Sailors' Song", "das Meer ist blau"), "Das Lied des Branntweinhändler" ("The Liquor Merchant's Song" or more literally "The Brandy Seller's Song"), "Das Lied von der harten Nuß" ("The Song of the Hard Nut"), and "Surabaya-Johnny." The last had lyrics Brecht originally wrote in 1925 for Feuchtwanger's Kolkatta 4. Mai. In that last case, we can all be happy they were in a rush and Brecht didn't have time to write something new, because Weill's setting of it is great, as really are all six Bills Ballhaus songs. (After the play flopped, not only did the pair rework "Mandelay" the next year for the expanded Mahagonny, but Weill self-plagiarized music from both "The Liquor Merchant's Song" and "Bilbao-Song" for his first American play, Johnny Johnson.)

Happy End premiered 2 September 1929 at Aufricht's Theater am Schiffbauerdamm. Carola Neher, Polly from Threepenny, played Lilian the Salvation Army girl. The stellar cast also included Peter Lorre, Oskar Homulka, Kurt Gerron, Theo Lingen, and Brecht's wife Helene Weigel. Act I apparently went fine, but the audience started to get restless in Act II as it became clear that the weak plot was not going to gel. Weigel broke character and went into a political harangue, attacking the bourgeois audience, quoting at length from Karl Marx, and basically guaranteeing a fiasco, though not quite as bad a one as Schebera and others have stated. Stephen Hinton says that contrary to the longstanding claim that the play closed after seven performances, advertisements in the Berliner Tageblatt show that it ran for a month, with six performances a week, so it had a little over 25 performances. Reviews were almost uniformly bad, although most of them noted that the songs were good (Rudolph Arnheim may have summed it up best: "Much good meat, but no skeleton.").

And good they were. It is unlikely that any other flop ever produced so many hit songs. Universal published single-song sheet music for "Matrosen-Song," "Bilbao-Song," and "Surabaya-Johnny." Lenya recorded "Bilbao-Song" and "Surabaya-Johnny," and the latter (along with "Pirate Jenny" from Threepenny) would remain one of her signature tunes for the next fifty years. The Lewis Ruth band, who had functioned as an orchestra for Happy End as they had for Threepenny, recorded four songs as instrumentals. Musical director Theo Mackeben recorded "Bilbao-Song," and "Surabaya-Johnny" under pseudonym Red Roberts with the Ultraphon jazz orchestra. The hits weren't as big as the year before, but those had been the biggest hits in inter-War Germany.

Weill viewed these songs as the culmination of a style: it was time for him to move on and let others try to repeat his commercial success by imitating. He had already begun to sketch out a different direction with the "radio" pieces. Now it was time to come back to the Mahagonny material with a new resolve. "If the bounds of opera cannot accommodate… a rapprochment with the theatre of the time (Zeittheater), then its bounds must be broken." And with the onset of the Depression, things were about to turn dark enough in Germany that Mahagonny would no longer seem so excessive in its left-wing attack on the immorality of capitalism.

[This essay draws heavily on Jürgen Schebera's meticulously researched Kurt Weill: an illustrated life, (Yale, 1995, translated from the original German by Caroline Murphy). There are also some after-the-fact corrections based on reading Stephen Hinton, Weill's Musical Theater: Stages of Reform (University of California, 2012).]

Next blog post: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

Next Weill biography blog post: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City