By date

- 8 March 2021: Welcome!

- 9 March 2021: Kurt Weill and John Cale

- 18 March 2021: Happy Birthday, Kurt Weill!

- 26 March 2021: Working on "Mussel From Margate" and "Jealousy Duet"

- 03 April 2021: The Young Kurt Weill in Dessau

- 16 April 2021: Weill's Student years (1)

- 26 April 2021: Face-to-face!

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 20 May 2021: Novembergruppe

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 28 June 2021: Schickelgruber (song)

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 12 July 2021: What Is 'Epic Theater'?

- 15 July 2021: What Keeps Mankind Alive? (song)

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 25 July 2021: Speak Low (song)

- 2 August 2021: Youkali (song)

- 9 August 2021: François Villon

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 23 August 2021: Not exactly a manifesto

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 18 October 2021: Kurt Weill and shadow puppetry

- 25 October 2021: Summer 1933

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 8 November 2021: The Eternal Road

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 13 December 2021: One Touch of Venus

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 3 January 2022: Jewish Kurt Weill

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- 28 February 2022: Down in the Valley

- 14 March 2022: Love Life

- 28 March 2022: Lost in the Stars

Kurt Weill biography

- 03 April 2021: The Young Kurt Weill in Dessau

- 16 April 2021: Weill's Student years (1)

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 25 October 2021: Summer 1933

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 8 November 2021: The Eternal Road

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 13 December 2021: One Touch of Venus

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 3 January 2022: Jewish Kurt Weill

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- 28 February 2022: Down in the Valley

- 14 March 2022: Love Life

- 28 March 2022: Lost in the Stars

Lotte Lenya biography

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

By topic

- Agnes de Mille

- Alabama Song

- Alan Jay Lerner

- Alan Paton

- Arnold Sundgaard

- Baden-Baden

- Ben Hecht

- Berlin

- 16 April 2021: Weill's Student years (1)

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 20 May 2021: Novembergruppe

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- Berlin Im Licht

- Berliner Requiem

- Bertolt Brecht

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 12 July 2021: What Is 'Epic Theater'?

- 15 July 2021: What Keeps Mankind Alive? (song)

- 9 August 2021: François Villon

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- Broadway opera

- Caspar Neher

- Charles Lindbergh

- Complainte de la Seine

- Danny Kaye

- Darren Loucas

- David Drew

- Der Neinsager

- Der Protagonist

- Die Bürgschaft

- Down in the Valley

- Dresden

- East Portland Blog

- Elia Kazan

- Elisabeth Hauptmann

- Elmer Rice

- Engelbert Humperdinck

- Epic theater

- Erika Neher

- Erwin Piscator

- Eternal Road

- Expressionism

- Felix Jackson

- Firebrand of Florence

- Franz Werfel

- Frauentanz

- Fritz Busch

- Georg Kaiser

- George Antheil

- Georges Rouault

- Gertrude Lawrence

- Hannah Höch

- Hans Curjel

- Hollywood

- Hyperinflation

- Ira Gershwin

- Ivan Goll

- Jealousy Duet

- Jean Cocteau

- Jewish Kurt Weill

- Joe Mabel

- 8 March 2021: Welcome!

- 9 March 2021: Kurt Weill and John Cale

- 26 March 2021: Working on "Mussel From Margate" and "Jealousy Duet"

- 16 April 2021: Weill's Student years (1)

- 26 April 2021: Face-to-face!

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 20 May 2021: Novembergruppe

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 28 June 2021: Schickelgruber (song)

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 12 July 2021: What Is 'Epic Theater'?

- 15 July 2021: What Keeps Mankind Alive? (song)

- 25 July 2021: Speak Low (song)

- 2 August 2021: Youkali (song)

- 9 August 2021: François Villon

- 23 August 2021: Not exactly a manifesto

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 25 October 2021: Summer 1933

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 8 November 2021: The Eternal Road

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 13 December 2021: One Touch of Venus

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 3 January 2022: Jewish Kurt Weill

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- 28 February 2022: Down in the Valley

- 14 March 2022: Love Life

- 28 March 2022: Lost in the Stars

- Johann Gottfried Herder

- John Cale

- Juliana Brandon

- 8 March 2021: Welcome!

- 18 March 2021: Happy Birthday, Kurt Weill!

- 26 March 2021: Working on "Mussel From Margate" and "Jealousy Duet"

- 26 April 2021: Face-to-face!

- 28 June 2021: Schickelgruber (song)

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 25 July 2021: Speak Low (song)

- 2 August 2021: Youkali (song)

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 23 August 2021: Not exactly a manifesto

- 18 October 2021: Kurt Weill and shadow puppetry

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

- Kuhhandel

- Kurt Weill

- 8 March 2021: Welcome!

- 9 March 2021: Kurt Weill and John Cale

- 18 March 2021: Happy Birthday, Kurt Weill!

- 26 March 2021: Working on "Mussel From Margate" and "Jealousy Duet"

- 03 April 2021: The Young Kurt Weill in Dessau

- 16 April 2021: Weill's Student years (1)

- 26 April 2021: Face-to-face!

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 20 May 2021: Novembergruppe

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 28 June 2021: Schickelgruber (song)

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 12 July 2021: What Is 'Epic Theater'?

- 15 July 2021: What Keeps Mankind Alive? (song)

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 25 July 2021: Speak Low (song)

- 2 August 2021: Youkali (song)

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 23 August 2021: Not exactly a manifesto

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 18 October 2021: Kurt Weill and shadow puppetry

- 25 October 2021: Summer 1933

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 8 November 2021: The Eternal Road

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 13 December 2021: One Touch of Venus

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 3 January 2022: Jewish Kurt Weill

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- 28 February 2022: Down in the Valley

- 14 March 2022: Love Life

- 28 March 2022: Lost in the Stars

- Léo Lania

- Lüdenscheid

- Lady in the Dark

- Langston Hughes

- Lost in the Stars

- Lotte Lenya

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- Lotte Reiniger

- Love Life

- Lys Symonette

- Mahagonny

- Man Without Qualities

- Marc Blitzstein

- Marlene Dietrich

- Mary Martin

- Maurice Abravanel

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- Max Reinhardt

- Maxwell Anderson

- Meyer Weisgal

- Moss Hart

- Mussel From Margate

- Nazizeit

- New York

- One Touch of Venus

- Otto Dix

- Otto Pasetti

- Paris

- Princess du Polignac

- Robert Vambery

- Roger Fernay

- S.J. Perelman

- Scherenschnitte

- Schickelgruber

- Seven Deadly Sins

- Shadow puppetry

- Silbersee

- Street Scene

- Threepenny Opera

- Tilly Losch

- Weill Project

- 8 March 2021: Welcome!

- 9 March 2021: Kurt Weill and John Cale

- 18 March 2021: Happy Birthday, Kurt Weill!

- 26 March 2021: Working on "Mussel From Margate" and "Jealousy Duet"

- 26 April 2021: Face-to-face!

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 28 June 2021: Schickelgruber (song)

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 15 July 2021: What Keeps Mankind Alive? (song)

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 25 July 2021: Speak Low (song)

- 2 August 2021: Youkali (song)

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 23 August 2021: Not exactly a manifesto

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 18 October 2021: Kurt Weill and shadow puppetry

- 25 October 2021: Summer 1933

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 8 November 2021: The Eternal Road

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 13 December 2021: One Touch of Venus

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 3 January 2022: Jewish Kurt Weill

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- 28 February 2022: Down in the Valley

- 14 March 2022: Love Life

- 28 March 2022: Lost in the Stars

- Weill Project Blog

- Weill family

- Weill's Second Symphony

- What Keeps Mankind Alive

- What Was Sent to the Soldier's Wife

- World War II

- World War II propaganda

- Young Kurt Weill

- Yvette Endrijautzki

- Zeitoper

- degenerate art

Tags

#kurtweill #georgkaiser #silbersee #nazizeit #lottelenya #casparneher #erikaneher #mauriceabravanel #ottopasetti #joemabel #weillproject #berlin #weillbio(Prior biographical posts on Weill: [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12]. Also, see this post on the Novembergruppe.)

Poster for the silent film The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, 1920. This horror film about a mad authority figure would doubtless also have been a great subject for an opera or musical theater piece in early 1930s Germany, but instead we got the marvel of the Weill/Kaiser Der Silbersee.

(This image is now public domain in the United States.)

So it is 1932 in Germany. Weill's Die Bürgschaft, with a libretto by Caspar Neher 🔗 is a critical success but, as recounted in our previous blog post, the rising Nazis are willing and able to terrorize theaters that show works of which they disapprove, so there is no corresponding commercial success. The Great Depression is raging, most theaters are either closed or cautiously booking classics.

The critic and theater director Paul Bekker, who had just directed Die Bürgschaft in Wiesbaden, writes an open letter to Weill proposing a Volksoper, a "folk" or "people's" opera, and Weill embraces the idea of "operas which can be preformed by laymen… when theaters are too dumb and cowardly to perform my works." Several attempts at the time went nowhere, though he would eventually come back to the concept in the 1940s in the United States with his Down in the Valley 🔗. Instead, Weill turned back to his sometime collaborator Georg Kaiser 🔗 (see earlier blog post on their play Der Protagonist and another blog post that discusses their one-act opera buffa Der Zar läßt sich photographieren, "The Tsar Has his Photograph Taken"). Initially, the two planned to come up with a musical version of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari 🔗. Like every other Weill/Kaiser project, it ended up going somewhere entirely unlike its original destination.

Weill at this point seems to have been carrying on a bit of wishful thinking. He and Lenya were drifting apart: he was carrying on a relationship with Caspar Neher's wife Erika (née Tornquist) and Lenya was working variously in the Soviet Union as well as Paris and Vienna, and soon in Vienna would take up with tenor Otto Pasetti (amazingly, no English-language Wikipedia article about Pasetti and only a brief one in German 🔗). That summer, Weill and Lenya would begin the process of an amicable divorce. The Nazis were rising to power, which would soon make it untenable for either Weill or Lenya to live or work in Germany or even, as it turns out, to get their assets out of the country. Nonetheless, with unwarranted optimism, the pair bought a house March 1932 in what was then known as the "artist's suburb" of Kleinmachnow, about half an hour from Berlin. And, despite the situation of German theater, Weill and Kaiser embarked on a beautiful and enigmatic work, Der Silbersee ("The Silver Lake"), subtitled Wintermärchen ("winter fairytale" or "winter's tale").

In the play, five unemployed men living in a cottage on the edge of town rob a grocery store to stave off starvation. Policeman Olim shoots their leader Severin (though not fatally) as they try to escape. Olim regrets this and when he soon wins a lottery he buys a mansion, gets Severin out of a police hospital, and takes him in. Severin has no idea that his benefactor is the same man who shot him, and given few things he has said about his desire for vengance, Olim would not dare to let him know. They hire two impoverished nobles as servants, Frau von Luber and Baron Laur. Frau von Luber's niece Fennimore is brought in, initially as an entertainer. She tells Severin the legend of the nearby Silver Lake that "can freeze over even in summer to save those in need."

Fennimore's performances for Olim and Severin range from light entertainment to the song "Caesars Tod" ("The Death of Caesar"), with a clear analogy to Hitler. There is a wide variety of music in the piece. The sixteen self-contained numbers range from tango, waltz, polka, and foxtrot to arias and a funeral march. The score requires twenty-four instruments—roughly half of them strings—plus a chorus. Of the onstage roles, only Fennimore and Severin require formally trained voices. The piece lasts about three hours and does not easily fit in any one genre. Most revivals have abridged it considerably but, remarkably, it was staged intact as the Weimar Republic collapsed.

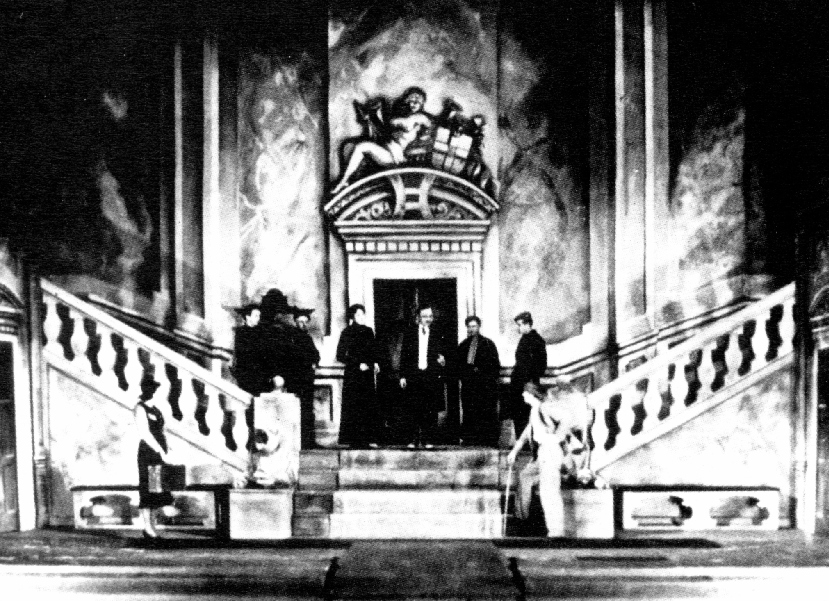

Olim's castle, from the Leipzig production of Silbersee. This grand set was built in the face of the almost certain knowledge that the play could have only a short run as the Nazis assumed power.

(Copyright status unknown, used on a fair use basis.)

Of course this fairytale cannot end happily, neither in life nor on stage. At most one can hope for a glimmer of redemption or hope, for something to go right amidst overall calamity. To paraphrase Chekhov's remark about a loaded gun, if you introduce a lake that can freeze over to save those in peril, you must have life-threatening peril in Act III. In the play, the two noble housekeepers turn out to be cuckoos in the nest and cheat Olim out of his mansion. Severin and Olim, defeated, go to drown themselves in the lake, but it has indeed frozen over despite warm spring weather. Led by Fennimore's voice, they step onto the ice and disappear in the distance. "Those who must go on will be carried by the silver lake."

In the real world of Germany in 1932, amidst the collapsing Weimar Republic, there was inevitably difficulty arranging a theater. Silbersee was completed 1 December 1932. Two days later, Schleicher's cabinet took over the reins of government, but everyone understood this was just a stopgap as Hindenberg and Hitler negotiated the terms on which the latter would be handed the reins of power. Weill, like many, thought Hitler would fail quickly, that the institutions of the Republic—especially the judiciary and the military—would stand up to him, and that Nazi rule would be a flash in the pan. Weill's publisher Universal Edition somehow convinced theaters in Leipzig, Magdeburg, and Erfurt to do a joint premiere, and Weill turned his attention to his next project, working with Caspar Neher and Hans Fallata on a Europa-Film adaptation of Fallata's novel Kleiner Mann, was nun? ("Little Man, What Now?"); Bertholdt Viertel was to direct. The film would eventually be made that summer, but without Weill or Viertel.

The Silbersee premieres were scheduled for 18 February 1933. On 30 January, Hitler effectively took power. Still, the Nazis did not move immediately to control the provincial theaters, so the planned premieres took place. On 18 February, Kaiser & Weill were in Leipzig, as were, in Hans Roche's words, "Everyone who counted in the German theater." The all "met together for the last time. And everyone knew this." Ernst Busch's recordings of "Lied vom Schlaraffenland" ("Song of the Land of Milk and Honey") and "Der Bäcker bäckt ums Morgenrot" ("The Baker Bakes for the Dawn"), with orchestral accompaniment under the baton of Maurice Abravanel, were rushed into release, but a further recording by Lotte Lenya and Gustav Brecher never came out; the masters are lost, probably deliberately destroyed by the Nazis. Universal Edition published a piano reduction in February 1933, plus a book of six pieces from the play.

The Reichstag in flames, and with it the last hopes for the survival of the Weimar Republic.

(This image is now public domain in the United States as seized enemy property. It remains copyrighted in Germany, but the Bundesarchiv, the German Federal Archive has licensed it: Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-R99859 / Unknown photographer / CC-BY-SA 3.0 🔗)

The play went over well in all three cities, but many of the favorable reviews had to be published abroad. The predictable Nazi attacks in the press were accompanied by overt threats, this time with government power to back them. The theaters successively bowed to the Nazi pressure, first Magdeburg, then Erfurt. The 4 March performance in Leipzig, five days after the Reichstag Fire 🔗 (27 February 1933), was to be the last public performance of Weill's music in Germany until the Nazis were finally defeated by the Allies in 1945, though of course many recordings of his music survived and were listened to surreptitiously.

Weill was fortunate not to be swept up immediately after the Reichstag Fire. He and Lenya were together in Munich at the time of the March 5 elections that confirmed Hitler's hold on power. She headed for Vienna, he back to Berlin, but not to their house in Kleinmachnow. Instead, he headed first for a hotel in Westend, then for the Nehers' home. On 15 March he met with Jean Renoir 🔗 to discuss a possible project in France. On 21 March Hindenburg officially handed over power to Hitler. Two days later, on the day that the Enabling Act effectively made Germany a dictatorship, Weill and the Nehers drove via Luxembourg to Paris. The Nehers eventually went back to Berlin; Weill moved into the Hotel Splendide. He would never set foot in Germany again, choosing not to visit even when he traveled to Europe after the War.

[This essay draws heavily on Jürgen Schebera's meticulously researched Kurt Weill: an illustrated life, (Yale, 1995, translated from the original German by Caroline Murphy).]

Next blog post: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

Next Weill biography blog post: Paris (1): an expedient harbor