By date

- 8 March 2021: Welcome!

- 9 March 2021: Kurt Weill and John Cale

- 18 March 2021: Happy Birthday, Kurt Weill!

- 26 March 2021: Working on "Mussel From Margate" and "Jealousy Duet"

- 03 April 2021: The Young Kurt Weill in Dessau

- 16 April 2021: Weill's Student years (1)

- 26 April 2021: Face-to-face!

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 20 May 2021: Novembergruppe

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 28 June 2021: Schickelgruber (song)

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 12 July 2021: What Is 'Epic Theater'?

- 15 July 2021: What Keeps Mankind Alive? (song)

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 25 July 2021: Speak Low (song)

- 2 August 2021: Youkali (song)

- 9 August 2021: François Villon

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 23 August 2021: Not exactly a manifesto

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 18 October 2021: Kurt Weill and shadow puppetry

- 25 October 2021: Summer 1933

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 8 November 2021: The Eternal Road

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 13 December 2021: One Touch of Venus

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 3 January 2022: Jewish Kurt Weill

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- 28 February 2022: Down in the Valley

- 14 March 2022: Love Life

- 28 March 2022: Lost in the Stars

Kurt Weill biography

- 03 April 2021: The Young Kurt Weill in Dessau

- 16 April 2021: Weill's Student years (1)

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 25 October 2021: Summer 1933

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 8 November 2021: The Eternal Road

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 13 December 2021: One Touch of Venus

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 3 January 2022: Jewish Kurt Weill

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- 28 February 2022: Down in the Valley

- 14 March 2022: Love Life

- 28 March 2022: Lost in the Stars

Lotte Lenya biography

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

By topic

- Agnes de Mille

- Alabama Song

- Alan Jay Lerner

- Alan Paton

- Arnold Sundgaard

- Baden-Baden

- Ben Hecht

- Berlin

- 16 April 2021: Weill's Student years (1)

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 20 May 2021: Novembergruppe

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- Berlin Im Licht

- Berliner Requiem

- Bertolt Brecht

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 12 July 2021: What Is 'Epic Theater'?

- 15 July 2021: What Keeps Mankind Alive? (song)

- 9 August 2021: François Villon

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- Broadway opera

- Caspar Neher

- Charles Lindbergh

- Complainte de la Seine

- Danny Kaye

- Darren Loucas

- David Drew

- Der Neinsager

- Der Protagonist

- Die Bürgschaft

- Down in the Valley

- Dresden

- East Portland Blog

- Elia Kazan

- Elisabeth Hauptmann

- Elmer Rice

- Engelbert Humperdinck

- Epic theater

- Erika Neher

- Erwin Piscator

- Eternal Road

- Expressionism

- Felix Jackson

- Firebrand of Florence

- Franz Werfel

- Frauentanz

- Fritz Busch

- Georg Kaiser

- George Antheil

- Georges Rouault

- Gertrude Lawrence

- Hannah Höch

- Hans Curjel

- Hollywood

- Hyperinflation

- Ira Gershwin

- Ivan Goll

- Jealousy Duet

- Jean Cocteau

- Jewish Kurt Weill

- Joe Mabel

- 8 March 2021: Welcome!

- 9 March 2021: Kurt Weill and John Cale

- 26 March 2021: Working on "Mussel From Margate" and "Jealousy Duet"

- 16 April 2021: Weill's Student years (1)

- 26 April 2021: Face-to-face!

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 20 May 2021: Novembergruppe

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 28 June 2021: Schickelgruber (song)

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 12 July 2021: What Is 'Epic Theater'?

- 15 July 2021: What Keeps Mankind Alive? (song)

- 25 July 2021: Speak Low (song)

- 2 August 2021: Youkali (song)

- 9 August 2021: François Villon

- 23 August 2021: Not exactly a manifesto

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 25 October 2021: Summer 1933

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 8 November 2021: The Eternal Road

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 13 December 2021: One Touch of Venus

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 3 January 2022: Jewish Kurt Weill

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- 28 February 2022: Down in the Valley

- 14 March 2022: Love Life

- 28 March 2022: Lost in the Stars

- Johann Gottfried Herder

- John Cale

- Juliana Brandon

- 8 March 2021: Welcome!

- 18 March 2021: Happy Birthday, Kurt Weill!

- 26 March 2021: Working on "Mussel From Margate" and "Jealousy Duet"

- 26 April 2021: Face-to-face!

- 28 June 2021: Schickelgruber (song)

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 25 July 2021: Speak Low (song)

- 2 August 2021: Youkali (song)

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 23 August 2021: Not exactly a manifesto

- 18 October 2021: Kurt Weill and shadow puppetry

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

- Kuhhandel

- Kurt Weill

- 8 March 2021: Welcome!

- 9 March 2021: Kurt Weill and John Cale

- 18 March 2021: Happy Birthday, Kurt Weill!

- 26 March 2021: Working on "Mussel From Margate" and "Jealousy Duet"

- 03 April 2021: The Young Kurt Weill in Dessau

- 16 April 2021: Weill's Student years (1)

- 26 April 2021: Face-to-face!

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 20 May 2021: Novembergruppe

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 28 June 2021: Schickelgruber (song)

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 12 July 2021: What Is 'Epic Theater'?

- 15 July 2021: What Keeps Mankind Alive? (song)

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 25 July 2021: Speak Low (song)

- 2 August 2021: Youkali (song)

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 23 August 2021: Not exactly a manifesto

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 18 October 2021: Kurt Weill and shadow puppetry

- 25 October 2021: Summer 1933

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 8 November 2021: The Eternal Road

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 13 December 2021: One Touch of Venus

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 3 January 2022: Jewish Kurt Weill

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- 28 February 2022: Down in the Valley

- 14 March 2022: Love Life

- 28 March 2022: Lost in the Stars

- Léo Lania

- Lüdenscheid

- Lady in the Dark

- Langston Hughes

- Lost in the Stars

- Lotte Lenya

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- Lotte Reiniger

- Love Life

- Lys Symonette

- Mahagonny

- Man Without Qualities

- Marc Blitzstein

- Marlene Dietrich

- Mary Martin

- Maurice Abravanel

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- Max Reinhardt

- Maxwell Anderson

- Meyer Weisgal

- Moss Hart

- Mussel From Margate

- Nazizeit

- New York

- One Touch of Venus

- Otto Dix

- Otto Pasetti

- Paris

- Princess du Polignac

- Robert Vambery

- Roger Fernay

- S.J. Perelman

- Scherenschnitte

- Schickelgruber

- Seven Deadly Sins

- Shadow puppetry

- Silbersee

- Street Scene

- Threepenny Opera

- Tilly Losch

- Weill Project

- 8 March 2021: Welcome!

- 9 March 2021: Kurt Weill and John Cale

- 18 March 2021: Happy Birthday, Kurt Weill!

- 26 March 2021: Working on "Mussel From Margate" and "Jealousy Duet"

- 26 April 2021: Face-to-face!

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 28 June 2021: Schickelgruber (song)

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 15 July 2021: What Keeps Mankind Alive? (song)

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 25 July 2021: Speak Low (song)

- 2 August 2021: Youkali (song)

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 23 August 2021: Not exactly a manifesto

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 18 October 2021: Kurt Weill and shadow puppetry

- 25 October 2021: Summer 1933

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 8 November 2021: The Eternal Road

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 13 December 2021: One Touch of Venus

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 3 January 2022: Jewish Kurt Weill

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- 28 February 2022: Down in the Valley

- 14 March 2022: Love Life

- 28 March 2022: Lost in the Stars

- Weill Project Blog

- Weill family

- Weill's Second Symphony

- What Keeps Mankind Alive

- What Was Sent to the Soldier's Wife

- World War II

- World War II propaganda

- Young Kurt Weill

- Yvette Endrijautzki

- Zeitoper

- degenerate art

Tags

#kurtweill #lottelenya #ottopasetti #tillylosch #julianabrandon #weillproject #lenyabio[Ed. note: Juliana picks up here from her prior posts on Lotte Lenya [1], [2] which ended with Lenya's great success in Threepenny Opera, which made her a star. For those of you who have been following along with my biographical posts on Kurt Weill, this is Lenya's parallel journey over the course of seven years, up to her arrival in America in September 1935. - JM]

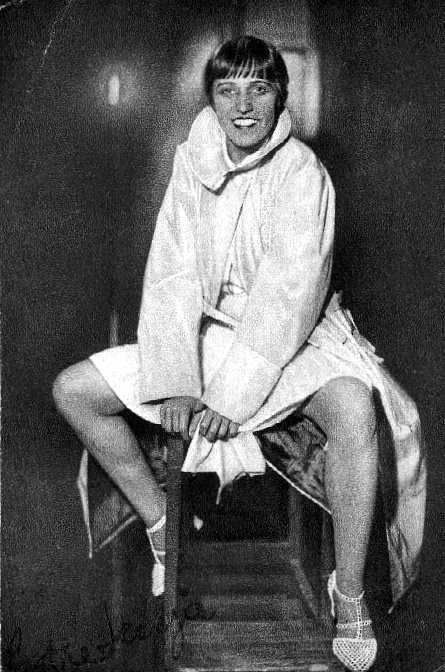

Lenya as Charmian Peruchacha in Lion Feuchtwanger's Petroleuminseln, 1928

Photographer and copyright status unknown, used here on a fair use basis.

In late 1928 Lenya played the role of Miss Charmian Peruchacha in Die Petroleuminseln ("The Petroleum Islands") at the Berlin State Theater, a play by Lion Feuchtwanger 🔗 with music by Weill. At the same time she was beginning rehearsals for the role of Ismene in Leopold Jessner's 🔗 Oedipus cycle, also at the Berlin State Theater. The reviews for her performance in Die Petroleuminseln 🔗 were somewhat mixed. Some thought she seemed too immature for the role, while others thought she was sensuous, energetic, and even "incomparable." Her reviews were likewise mixed for Ismene, where she was described as "a great success" while also apparently needing greater variety in the way she spoke her lines. She seemed to take this review to heart as her acting was considered much improved when she appeared as Alma beside Peter Lorre in Pioneers in Ingolstadt 🔗 by Marieluise Fleißer's 🔗 (a lover of Brecht's.) The play itself, however, was considered a flop at the time, in spite of the controversial staging (for instance, Lenya had a sex scene in a graveyard), or possibly even because of it. A case could be made that Brecht's insistence on giving the play plenty of shock value distracted from the actual message.

In December 1928 Lenya's abusive father died, but she hadn't had contact of any sort with him since she left for Zurich in 1921. It's hard to know what kind of effect this news had on her.

Weill and Brecht were still working on the Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny when they churned out Happy End in the middle of it all (see prior blog post). Lenya was not available to perform in it because she was busy with a small role in a play by Georg Büchner 🔗 called Danton's Death, written in 1835. This play called for a more romantic style of acting than Lenya was now used to since, under Brecht's influence, she had been honing a more naturalistic style. While Happy End was not a success, several of the songs from it were. "Bilbao Song" (you can hear Lenya singing that here 🔗) and "Surabaya Johnny" (similarly 🔗) went on to become staples of Lenya's repertoire for the rest of her life, even though these songs were not written expressly for her.

The Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny finally had its premiere in Leipzig on March 9, 1930. Lenya was in the audience with Weill and his parents, who lived in Leipzig, witnessing with horror how Nazis started a riot in the audience. (You can read more about the struggles with Mahagonny here, in Joe's earlier blog post.)

As Joe wrote earlier, it took a while for this Mahagonny opera to get produced in Berlin. Weill hadn't intended the role of Jenny to be played by Lenya because he was peddling the piece to opera houses which required opera singers, but when all the Berlin opera houses rejected it he could rewrite the role with Lenya's voice in mind. Now Lenya had a draw of her own and her voice was showcased in the now greatly expanded role of Jenny. The opera had its Berlin premiere on December 21, 1930 and it was much more peaceful than in Leipzig. Lenya had rave reviews commenting on her boldness, confidence, energy, and unique voice. (Here she is singing "Wie man sich bettet" from Mahagonny 🔗, generally known in English as "We All Make the Bed We Must Lie In".)

In 1931 Erwin Piscator called Lenya and invited her to take a role in a movie he was working on, his first, based on a novel by Anna Seghers 🔗 called The Revolt of the Fishermen of St Barbara. Lenya would play a sailor's whore, a very similar role to that of Jenny in Threepenny (seems she was always a Jenny.) The filming was to take place in Russia with a combined Russian and German cast and crew.

The Germans were put up in a rundown hotel in Moscow. Lenya noted that her chair collapsed when she put her suitcase down on it, the faucet came off in her hand, and rats ate her leftover dinner in the night. The filming was supposed to take place in Odessa, but everyone waited and waited. After three months the Germans were sent home without having filmed a thing. Piscator eventually finished the film two years later 🔗, but Lenya was not in it.

The house Weill bought in Kleinmachnow, photographed in 2013.

Photo by Andreas Lippold, used under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

On Lenya's 33rd birthday, October 18, 1931, Weill called her in Moscow with a surprise. He had bought a house! It was not ready to move into when she returned to Berlin, but there was another surprise. Lenya discovered that Weill had a lover in Erika Neher, Caspar Neher's wife (the designer for Threepenny). On one hand Lenya was happy that Caspar finally realized he was homosexual, but she also considered this affair to be quite dangerous for her because of how emotionally involved Weill was with Erika.

Though Lenya took some time picking out furnishings for the new house she never completely moved herself into it. Hot on the heels of her Russian film disaster was an offer to perform in a shortened version of Mahagonny in Vienna. Lenya and Weill went together in the spring of 1932. It was while working on this production that Lenya met the very attractive tenor and member of the minor nobility, Otto von Pasetti, and started a rather long-lasting affair with him. (Hear Pasetti's 1931 recording of Weill's Mussel von Margate here 🔗.) [Ed. note: got to say, I like Juliana's own rendition of it better than Pasetti's. Stay tuned for a chance to hear that. - JM]

While back in Vienna, Lenya visited her mother, and was horrified to find that her drunk, abusive boyfriend had been released from prison and they were living together once more. Lenya visited for only a few hours and high tailed it out of there.

The casino at Monte Carlo: ca. 1905, but probably not too much changed by the time Lenya got there.

[Ed. note: no doubt. Not much changed by the time I saw it in 1996. - JM]

Public domain.

Instead of returning to Berlin with Weill, Lenya went off to Monte Carlo with Pasetti. She and Pasetti shared a lifelong love of gambling and lost a small fortune in the casinos of Monte Carlo. Weill continued to send Lenya money when she needed it, as well as 100 schillings a month to her mother, though he also recommended to Lenya that she start looking for work. He told her of an opportunity to sing in Paris where a French version (different not just in language, but in structure) of Mahagonny Songspiel was being put together. [Ed. note: this was the concert at the Salle Gaveau that I wrote about in an earlier blog post about Weill. - JM] Weill had been invited to supervise this production himself, and promised his wife that she would be well paid for singing in it. Pasetti was also offered a role in it, so Lenya ran off with him to Paris as soon as she could.

The Paris production was a hit. Lenya received rave reviews stating that she was "…the overwhelming interpreter of a music on the borders of romanticism and the art of the music hall." It was at this time that Lenya opened up talk with Weill about getting a divorce. Things with Pasetti were quite serious, though apparently more serious on his end than hers. Pasetti mentioned that he wanted to have a child with her (apparently Lenya didn't yet know she couldn't conceive), which she mentioned to Weill. Weill said, "That would hurt me very much," so Lenya told Pasetti no.

Lenya made friends in Paris with the homosexual artist circle surrounding Jean Cocteau 🔗 and André Gide 🔗. Cocteau was the one who started creating a certain mystique around Lenya that helped to turn her into an icon. It was with this new circle of friends that Lenya felt safe confiding that she had had some brief sexual dalliances with women in the past and now was interested in having a real affair with a woman, but her time in Paris was too short-lived to find the right person. Early in 1933, she accompanied her husband to the German border and then returned to Paris with Pasetti, heading back to Vienna around the new year. It's very difficult to pinpoint Lenya's travels between 1932 and 1935 because she had the relevant pages very carefully removed from her passport.

Shortly after the premiere of Weill's Der Silbersee in January 1933 it became clear that Weill, being Jewish, was not welcome in Germany. [Ed. note: That's putting it mildly. See prior blog post. - JM] They had a friend who infiltrated the secret police to access the list of citizens to be arrested so he could warn them. Weill and Lenya were next on the list, but warned by their friend they were able to escape. They took the Nehers with them, as Erika was still Kurt's lover. Just outside of Berlin Lenya asked them to stop the car. She got out, promised to protect Weill's assets in Berlin as best she could and went her own way, south to Pasetti. Weill and the Nehers went on to Paris. Lenya later had quite an embellished tale to tell about their escape from Germany, but in reality she didn't know how Kurt got out until 1953 when she asked Caspar Neher for the story. Weill couldn't return to Germany, but Lenya did return to their house with Pasetti to remove any evidence the Nazis could use against any of their theatrical collaborators, bring other important items back to Weill, and to take care of their finances. Many of Weill's things ended up in a storage facility in Innsbruck, Austria, paid for by Pasetti's father.

Having just spent the winter making friends and various professional contacts in Paris, Weill was able to secure a nice place to live and many more commissions, including one for the ballet/song cycle called The Seven Deadly Sins, which was to be his last collaboration with Brecht. (More on this in a prior blog post.) This piece was written around Lenya as singer and Tilly Losch as dancer. Lenya happily returned to Paris to perform this piece, especially since it also included a part for Pasetti. Paris was still an option Lenya could consider as a safe place to settle down. She couldn't make up her mind on that front, though a letter from May 8, 1933 has Lenya considering another name change to "L. Marie Lenja" in order to sound less German, and perhaps a tad more French.

Lenya seemed to be more of a hit than Weill's music, which the French audience found rather strange. Virgil Thomson, then living in Paris, saw Seven Deadly Sins and his review of Lenya is worth noting: "Madame Lenya sings, or rather croons, with an impeccable diction that reaches the farthest corner of any hall and with an intensity of dramatization and a sincerity of will that are very moving. She is, moreover, beautiful in a new way, a way that nobody has vulgarized so far." In spite of its seeming failure in Paris, Seven Deadly Sins was translated into English with the new title Anna-Anna, and Lenya traveled to London for that premiere, apparently very worried that her English wouldn't be good enough. Weill saved all her press clippings from London and encouraged her to get a manager. All this just days from their divorce being finalized. Many of their friends said they didn't even realize the two of them had gotten a divorce. Their letters certainly show that they were still very much caring for one another, even continuing to use pet names. Mahagonny Songspiel was also premiered in London where Lenya was reviewed by Constant Lambert, "(she) put into the word 'baloney' a wealth of knowingness which makes Mae West seem positively ingenue."

Paris relaunched Mahagonny Songspiel, which they apparently really liked, and Lenya was cast once again beside her lover Pasetti, but she was now also having a passionate affair with Tilly Losch, finally realizing her desire for a real affair with a woman, though it didn't seem to last long.

Lenya spent most of 1933 wandering all over Europe with Pasetti, gambling and asking Weill for more money. She had a "gambling plan" and was very clear with Weill about what that plan was, giving details in letters about how successful she was with it and when it failed. In turn it sounds like Weill heartily encouraged this plan! The money she made from gambling actually helped make up some of the losses from having to flee Germany. Throughout the summer and fall they sent letters back and forth: Lenya at their house in Berlin, and Kurt bouncing between Italy and Paris. During this time their letters were full of cryptic details about who needed to be paid and how they would get their stuff out of Germany, but because they knew their letters were likely being read by the police they used "Munich" as code for Paris and "Julian" as code for Kurt Weill himself, so "I'm sending money to Julian" meant that Lenya was sending Kurt some money. These letters are also full of talk about what to do about their dog, a German shepherd named Harras, and their housekeeper. It seems the housekeeper was still living at their house in Berlin taking care of the dog, and being paid the whole time, which is evidence that while the whole Nazi situation gave Lenya and Weill a big financial hit, they were still pretty well off.

Their divorce was finalized on September 18, 1933, and shortly after Weill started talking to his friends about how to get Lenya back. He had settled in a large house in Louveciennes just outside Paris (which used to be the servants' quarters for Madame du Barry, and which apparently had a tree growing in the middle of it), and he asked Lenya to come live with him there, saying she could even bring Pasetti… knowing that he wouldn't be down with such a ménage. There was trouble brewing between Lenya and Pasetti anyway. She was now considering trying to find an American to marry so she could cross the ocean and seek citizenship there. Meanwhile Weill's musical prospects were beginning to look better in New York than in Paris as he began work on what would become The Eternal Road (see yet another prior blog post), but which he and Lenya called "that Bible thing."

Though divorced, Lenya and Weill still wrote to each other constantly not only to discuss what to do with their shared assets but to talk about their lives, make plans for the future, and to just joke around. Weill also said in almost every letter that Lenya should learn French and English in preparation for wherever they would end up living, clearly still thinking in terms of a future with her at least nearby. Weill had seemed to settle in Paris, but Lenya wasn't sure where she should set up a permanent residence. She had reservations about Italy, but stayed there for about one year, performing in Mahagonny in Rome in December of 1933.

Lenya was constantly on the move throughout 1934, though mostly gambling with Pasetti in Italy in between trying to settle Weill's financial situation in Berlin. In August she took on a role as Pussy Angora in an operetta by Walter Kollo 🔗 called Lieber reich aber glücklich ("I'd rather be rich than happy"), at the Corso Theater in Zurich. This was the first acting she had done in anything other than her husband's work in four years. While in Zurich she ran into Richard Révy 🔗 and her former Czechoslovakian lover who inadvertently financed her escape to Berlin. In a letter to Révy she remarks how angry he looked seeing her dining with three handsome men and not appearing to be "down and out" at all.

The house Weill had bought in Berlin was finally sold in October of 1934. Pasetti helped with the sale, but then stole the money, as well as one of their cars, and ran off. [Ed. note: Wow. I didn't know that, and it's not in any of the several Weill biographies I'd read. Definitely explains that breakup. - JM] That was the end of that affair. Lenya and Weill hoped to see their money again some day, but that never happened, and Lenya would go off about what a lying crook Pasetti was for the rest of her life. After this she went to Paris, but stayed in a cheap hotel rather than go live with Weill despite his consistent offer. Then she cut her wrists in a suicide attempt, an episode in her life she didn't really talk much about. She wanted to reconcile with Weill as much as he wanted to, but neither thought it was even possible.

Instead, Lenya began an affair with the painter and founding father of surrealism, Max Ernst 🔗. This affair had shades of her romance with Weill in that Ernst always put his work first, so the affair was not to last, but Ernst was physically there for her in her time of need, even visiting her in the hospital in February 1935 when she had surgery for polyps on her belly. She and Weill had a nickname for the polyps, Zippi, a term that also became his nickname for her during that time. Weill kept telling her to move out of her cheap hotel and recover at Louveciennes, since he was in London anyway. Finally she relented, and the offer was probably sweetened this time because their dog Harras was now there. Some time before Weill's trip to London, Harras had been returned to him, which was a very exciting and joyful reunion, but now the dog was being cared for by the Louveciennes caretakers. Lenya's presence was probably a great comfort to the dog and he was likely a comfort to her.

Weill was in London trying to get his musical A Kingdom for a Cow staged. [Ed. note: this is touched on in the last couple of paragraphs of a previous blog post. - JM] He wrote Lenya many letters trying to convince her to join him there, including descriptions of apartments he was looking at for her. He wrote that he thought he had finally resolved the problem of their living together, which had apparently been an issue of contention that was a contributing factor in their divorce.

However, it seemed that Lenya and Weill were always two ships passing in the night. Lenya joined her husband in London on April 8, 1935 where they were together until June through the premiere of Kingdom for a Cow, which was a total failure. [Ed. note: a mixed bag critically, but in commercial terms "total failure" is on the mark. - JM] Weill, drained from this "flop" went back to Louveciennes while Lenya stayed in London. Weill needed a vacation but quickly went back to work on what would become The Eternal Road. Preparations were being made to stage "the Bible thing" in New York, so Weill's letters to Lenya start convincing her to come along with him to America.

Lenya didn't make up her mind to come with him to America until the last minute. Even then it was assumed that the two would return to Paris after the run for Eternal Road was over, so they left Harras with the caretakers of the house in Louveciennes once more and boarded the SS Majestic on September 4, 1935 for New York. When Lenya saw the New York skyline she said "it really felt like coming home."

Here's a nice timeline of this era, from 1932 to 1950, on The Weill Foundation's website 🔗 in case this particular flow of events proves confusing. Lenya moved around so much during this period that I certainly got confused.

[This blog post borrows from the books Lenya: A Life by Donald Spoto 🔗 and Speak Low: the letters of Kurt Weill and Lotte Lenya, edited by Lys Symonette and Kim H. Kowalke.]

Next blog post: A period of adjustment