By date

- 8 March 2021: Welcome!

- 9 March 2021: Kurt Weill and John Cale

- 18 March 2021: Happy Birthday, Kurt Weill!

- 26 March 2021: Working on "Mussel From Margate" and "Jealousy Duet"

- 03 April 2021: The Young Kurt Weill in Dessau

- 16 April 2021: Weill's Student years (1)

- 26 April 2021: Face-to-face!

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 20 May 2021: Novembergruppe

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 28 June 2021: Schickelgruber (song)

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 12 July 2021: What Is 'Epic Theater'?

- 15 July 2021: What Keeps Mankind Alive? (song)

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 25 July 2021: Speak Low (song)

- 2 August 2021: Youkali (song)

- 9 August 2021: François Villon

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 23 August 2021: Not exactly a manifesto

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 18 October 2021: Kurt Weill and shadow puppetry

- 25 October 2021: Summer 1933

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 8 November 2021: The Eternal Road

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 13 December 2021: One Touch of Venus

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 3 January 2022: Jewish Kurt Weill

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- 28 February 2022: Down in the Valley

- 14 March 2022: Love Life

- 28 March 2022: Lost in the Stars

Kurt Weill biography

- 03 April 2021: The Young Kurt Weill in Dessau

- 16 April 2021: Weill's Student years (1)

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 25 October 2021: Summer 1933

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 8 November 2021: The Eternal Road

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 13 December 2021: One Touch of Venus

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 3 January 2022: Jewish Kurt Weill

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- 28 February 2022: Down in the Valley

- 14 March 2022: Love Life

- 28 March 2022: Lost in the Stars

Lotte Lenya biography

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

By topic

- Agnes de Mille

- Alabama Song

- Alan Jay Lerner

- Alan Paton

- Arnold Sundgaard

- Baden-Baden

- Ben Hecht

- Berlin

- 16 April 2021: Weill's Student years (1)

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 20 May 2021: Novembergruppe

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- Berlin Im Licht

- Berliner Requiem

- Bertolt Brecht

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 12 July 2021: What Is 'Epic Theater'?

- 15 July 2021: What Keeps Mankind Alive? (song)

- 9 August 2021: François Villon

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- Broadway opera

- Caspar Neher

- Charles Lindbergh

- Complainte de la Seine

- Danny Kaye

- Darren Loucas

- David Drew

- Der Neinsager

- Der Protagonist

- Die Bürgschaft

- Down in the Valley

- Dresden

- East Portland Blog

- Elia Kazan

- Elisabeth Hauptmann

- Elmer Rice

- Engelbert Humperdinck

- Epic theater

- Erika Neher

- Erwin Piscator

- Eternal Road

- Expressionism

- Felix Jackson

- Firebrand of Florence

- Franz Werfel

- Frauentanz

- Fritz Busch

- Georg Kaiser

- George Antheil

- Georges Rouault

- Gertrude Lawrence

- Hannah Höch

- Hans Curjel

- Hollywood

- Hyperinflation

- Ira Gershwin

- Ivan Goll

- Jealousy Duet

- Jean Cocteau

- Jewish Kurt Weill

- Joe Mabel

- 8 March 2021: Welcome!

- 9 March 2021: Kurt Weill and John Cale

- 26 March 2021: Working on "Mussel From Margate" and "Jealousy Duet"

- 16 April 2021: Weill's Student years (1)

- 26 April 2021: Face-to-face!

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 20 May 2021: Novembergruppe

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 28 June 2021: Schickelgruber (song)

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 12 July 2021: What Is 'Epic Theater'?

- 15 July 2021: What Keeps Mankind Alive? (song)

- 25 July 2021: Speak Low (song)

- 2 August 2021: Youkali (song)

- 9 August 2021: François Villon

- 23 August 2021: Not exactly a manifesto

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 25 October 2021: Summer 1933

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 8 November 2021: The Eternal Road

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 13 December 2021: One Touch of Venus

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 3 January 2022: Jewish Kurt Weill

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- 28 February 2022: Down in the Valley

- 14 March 2022: Love Life

- 28 March 2022: Lost in the Stars

- Johann Gottfried Herder

- John Cale

- Juliana Brandon

- 8 March 2021: Welcome!

- 18 March 2021: Happy Birthday, Kurt Weill!

- 26 March 2021: Working on "Mussel From Margate" and "Jealousy Duet"

- 26 April 2021: Face-to-face!

- 28 June 2021: Schickelgruber (song)

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 25 July 2021: Speak Low (song)

- 2 August 2021: Youkali (song)

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 23 August 2021: Not exactly a manifesto

- 18 October 2021: Kurt Weill and shadow puppetry

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

- Kuhhandel

- Kurt Weill

- 8 March 2021: Welcome!

- 9 March 2021: Kurt Weill and John Cale

- 18 March 2021: Happy Birthday, Kurt Weill!

- 26 March 2021: Working on "Mussel From Margate" and "Jealousy Duet"

- 03 April 2021: The Young Kurt Weill in Dessau

- 16 April 2021: Weill's Student years (1)

- 26 April 2021: Face-to-face!

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 20 May 2021: Novembergruppe

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 28 June 2021: Schickelgruber (song)

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 12 July 2021: What Is 'Epic Theater'?

- 15 July 2021: What Keeps Mankind Alive? (song)

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 25 July 2021: Speak Low (song)

- 2 August 2021: Youkali (song)

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 23 August 2021: Not exactly a manifesto

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 18 October 2021: Kurt Weill and shadow puppetry

- 25 October 2021: Summer 1933

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 8 November 2021: The Eternal Road

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 13 December 2021: One Touch of Venus

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 3 January 2022: Jewish Kurt Weill

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- 28 February 2022: Down in the Valley

- 14 March 2022: Love Life

- 28 March 2022: Lost in the Stars

- Léo Lania

- Lüdenscheid

- Lady in the Dark

- Langston Hughes

- Lost in the Stars

- Lotte Lenya

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- Lotte Reiniger

- Love Life

- Lys Symonette

- Mahagonny

- Man Without Qualities

- Marc Blitzstein

- Marlene Dietrich

- Mary Martin

- Maurice Abravanel

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- Max Reinhardt

- Maxwell Anderson

- Meyer Weisgal

- Moss Hart

- Mussel From Margate

- Nazizeit

- New York

- One Touch of Venus

- Otto Dix

- Otto Pasetti

- Paris

- Princess du Polignac

- Robert Vambery

- Roger Fernay

- S.J. Perelman

- Scherenschnitte

- Schickelgruber

- Seven Deadly Sins

- Shadow puppetry

- Silbersee

- Street Scene

- Threepenny Opera

- Tilly Losch

- Weill Project

- 8 March 2021: Welcome!

- 9 March 2021: Kurt Weill and John Cale

- 18 March 2021: Happy Birthday, Kurt Weill!

- 26 March 2021: Working on "Mussel From Margate" and "Jealousy Duet"

- 26 April 2021: Face-to-face!

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 28 June 2021: Schickelgruber (song)

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 15 July 2021: What Keeps Mankind Alive? (song)

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 25 July 2021: Speak Low (song)

- 2 August 2021: Youkali (song)

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 23 August 2021: Not exactly a manifesto

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 18 October 2021: Kurt Weill and shadow puppetry

- 25 October 2021: Summer 1933

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 8 November 2021: The Eternal Road

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 13 December 2021: One Touch of Venus

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 3 January 2022: Jewish Kurt Weill

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- 28 February 2022: Down in the Valley

- 14 March 2022: Love Life

- 28 March 2022: Lost in the Stars

- Weill Project Blog

- Weill family

- Weill's Second Symphony

- What Keeps Mankind Alive

- What Was Sent to the Soldier's Wife

- World War II

- World War II propaganda

- Young Kurt Weill

- Yvette Endrijautzki

- Zeitoper

- degenerate art

Tags

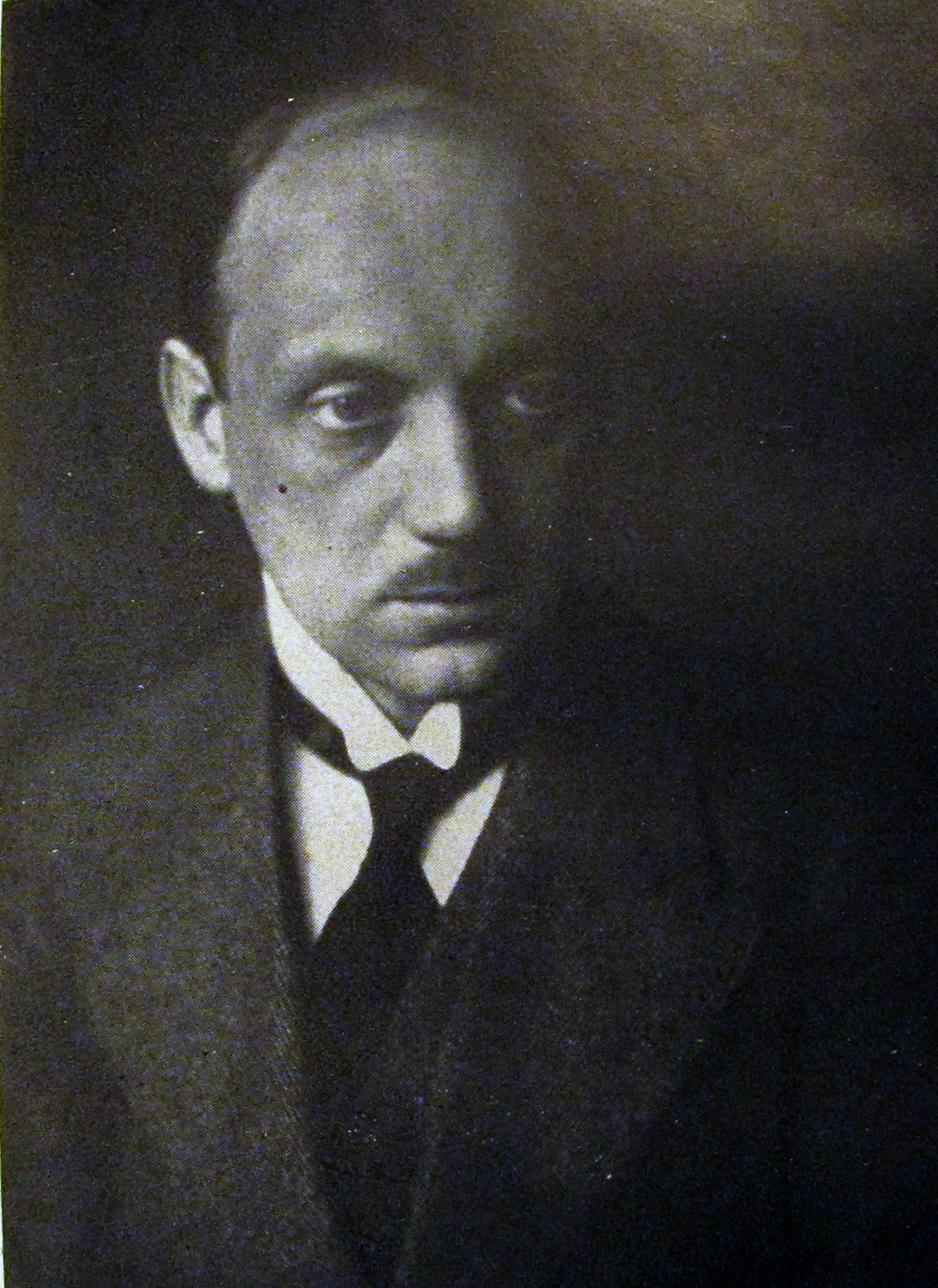

#kurtweill #joemabel #berlin #dresden #fritzbusch #georgkaiser #derprotagonist #frauentanz #lottelenya #weillbio(Prior posts on Weill's youth and student years: [1], [2], [3], [4]. Also, see this recent post on the Novembergruppe.)

By the time Weill graduated at the end of 1923 from Ferruccio Busoni's master class at the Preußische Akademie der Künste (Prussian Academy of the Arts), he had already written the ballet pantomime Die Zaubernacht (soon to be his first piece performed in the U.S.); the Berlin Philharmonic had performed his Divertimento for Small Orchestra and Male Chorus and Sinfonia Sacra: Fantasia, Passacaglia und Hymnus für Orchester; the Hindemith-Amar Quartet had prominently featured his String Quartet, Op. 9 in Frankfurt. His final project for Busoni, the a capella choral cycle Recordare: Lamentations of Jeremiah, Chapter 5 was circulating in manuscript: considered brilliant but unperformably complex at the time, it was finally performed in the 1970s. His Frauentanz, Op. 10, a rhythmically complex setting of several medieval Minnesang 🔗 texts, fared better: it was on the verge of its first public performance. He had long since left behind playing for tips in a Bierkeller, and was a prominent member of the Novembergruppe, Weimar Germany's leading organization of left-leaning artists and musicians.

Berlin and Germany were emerging from the hyperinflation 🔗. The five years between that and the Great Depression would be the last really hopeful time for the arts in Germany until the two Germanies' reemergence after World War II.

In something of a transition out of his studies, Weill's brief, intense Frauentanz premiered in February 1924 at the Preußische Akademie from which he had just graduated, sung by Nora Pisling-Boas under the direction of Fritz Stiedry. It would later make a big splash in August 1924 at the Second Chamber Music Festival of the International Society for Contemporary Music (ISCM), sung by Lotte Leonard and conducted by Philipp Jarnach. Jarnach and Weill had become close after Weill's mentor Busoni referred Weill to Jarnach as a teacher to strengthen Weill's counterpoint skills. Weill brought Jarnach into the Novembergruppe.

In April 1924, three month's before Busoni's death, Weill signed a 10-year contract with Emil Hertzka at Vienna-based music publisher Universal Edition. Thanks to that contract, we have scores, piano reductions, and sometimes even multiple arrangements for most of Weill's work from the latter part of his student years onward. The documentary value of these varies—especially in his period working with Bertolt Brecht, a piece might undergo continual revisions, and it is hard to call one version definitive—but it means that despite the chaos of Nazizeit, the book-burnings, and the Holocaust, most of Weill's work survives. (Unpublished works held at Universal were sadly lost after the Anschluss, when the Nazis marched unopposed into Austria in 1938.)

Although Busoni's health was failing, he still gave Weill what turned out to be the key connection for the next phase of his career. Before Weill and other Busoni pupils headed to the Semperoper in Dresden in November 1923 to attend a performance of Busoni's Arlecchino, Busoni recommended Weill to the Semperoper's conductor/manager Fritz Busch. Busch and Weill got together when Weill came to Dresden and Busch subsequently introduced Weill to dramatist Georg Kaiser 🔗 with the idea that Kaiser and Weill could collaborate on ballet with lyrics for a Dresden production.

Kaiser was one of the most important German playwrights of the era, and almost certainly the most prolific. At 46, he was a generation older than the 23-year-old Weill. At this time Kaiser had already written at least 45 plays. Seven of these premiered in the 1921-22 season, leading some to question whether he really was one playwright or a front for a group. He did not have a history of having music in his plays, and had systematically opposed others' plans to do operas based on his works, but he'd been in the audience a year earlier at the Theater am Kurfürstendamm for Die Zaubernacht, the ballet pantomime for children that Weill wrote with choreographer/librettist Wladimir Boritsch, and he'd liked what he'd heard. Probably no one was as surprised as Weill when they came out of their initial meeting with a firm decision to plunge into the project for Busch.

Kaiser lived northwest of Berlin at Grünheide bei Erkner, a lake district that at the time was the summer residence of many wealthy Berliners. Weill would become a frequent visitor during the project, first in January and February 1924 and again that summer.

At first, the project came very quickly but by Weill's account some time in February they went from thinking, "We're about three-quarters of the way there" to thinking "this is too big for a pantomime, it needs to become an opera." It's not clear whether the pantomime as such was at all closely based on Kaiser's 1922 play Der Protagonist, but that was very much the basis for the opera when they got back to it that summer.

Meanwhile, Weill headed off to Davos to visit his distant cousin (and probably lover) Nelly Frank, then traveled on to Milan (where he saw Toscanini conduct at La Scala), Florence, Bologna, and Rome. He came back to Berlin and wrote his Concerto for Violin and Wind Orchestra, Op. 12 in April and May, his last strictly instrumental work for many years to come. This unusual piece (violin and wind orchestra is not exactly a common pairing) was not performed at the time, but premiered the next year in Paris, and eventually made a sensation when violinist Stefan Frenkel (later concertmaster of New York's Metropolitan Opera) performed it, first on October 1925 in Weill's home town of Dessau and then at the International Society for Contemporary Music festival in Zurich in 1926. It would become a staple of Frenkele's repertoire.

In June of 1924, Weill and Kaiser got back to work at Grünheide, with Weill coming and going from Berlin by train. One of those trips out proved to be among the most important events of Weill's life. It was a long way by land from the train station to Kaiser's home, but a relatively short trip by water. One day when Weill was coming out to Grünheide, Kaiser asked a houseguest to row across the lake and pick him up at the station. That houseguest was the young actress Lotte Lenya. The two immediately formed a strong connection, moved in together in May 1925, and eventually married. And divorced. And remarried. The Weill/Lenya relationship deserves a blog post of its own—or two or three [Ed. note August 2021: or more. For starters, see Juliana's post on the song "Nannas Lied" and on Lenya's youth.]—but suffice it to say for now that with his mentor Ferruccio Busoni on his deathbed (he died in August 1924), another equally important figure was entering Weill's life. One teaser on that future blog post: while Lenya rowed him across the lake, he realized he had seen her before.

The expanded Protagonist project proved to be more than a summer's work. Kaiser would work on the libretto until the end of 1924. Meanwhile, Weill composed Das Stundenbuche: Orchesterlieder nach texten von Rilke, Op. 13. Only fragments of this "Book of Hours" survive, but we know it consisted of two three-song cycles, and that it premiered 22 Jan 1925 at the Berlin Philharmonic, with baritone Manfred Lewandowsky and conductor Heinz Unger. Separately from that, at roughly the same time as the libretto arrived, Weill started a side job writing for Der deutsche Rundfunk, a weekly radio guide. By the time he and the magazine parted ways, he would write over 400 articles. Much of this was as a music critic in the obvious sense but when Weill got the job Germany had only started radio broadcasting about two years earlier, so he also gave a lot of consideration to what did and didn't work in this new medium.

Weill completed Der Protagonist in April 1925 and on 21 May 1925, visiting Dresden for the posthumous premiere of Busoni's Doktor Faustus, he spent the day with Fritz Busch and could tell him the work was ready. Busch originally hoped to premiere the piece at the Semperoper in Dresden in late autumn 1925, but Heldentenor Kurt Taucher had a U.S. tour scheduled, so the premiere did not occur until 27 March 1926.

It was a hit. 20 minutes of applause, 40 curtain calls. It went on to be performed at 15 different opera houses in Germany, and, in Jürgen Schebera's words "launched Weill as a composer of opera." Emil Hertzka at Universal Edition was clearly impressed. He'd been breakfasting daily with Weill at a restaurant, always ordering the cheap standard breakfast for the two of them. The morning after the premiere, he handed the menu to Weill and told him to order whatever he wanted. "It is really quite exciting to become famous overnight," Weill wrote to his parents.

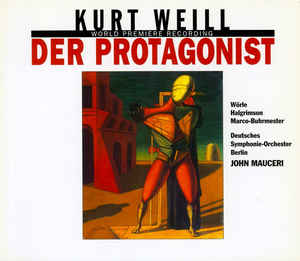

Album jacket, Capriccio recording of Der Protagonist, Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin, directed and conducted by John Mauceri.

I'll readily admit that until I started the Weill Project all I knew of Der Protagonist was its existence and that it was one of the culminating pieces of Weill's earlier style. Although often performed in Germany in the Weimar years, it wasn't performed there again until 1958. It's occasionally been done since then in various locales (although Wikipedia tells me, for example, that the Austrian premiere was not until 2000). It was finally recorded in 2001 (Wikipedia incorrectly says 2002); I now have a copy of that recording, by the Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin, directed and conducted by John Mauceri, with Robert Wörle in the title role.

In hindsight, the libretto of Der Protagonist can be read as a manifesto for the what Weill and Bertolt Brecht would come to call "epic" theater (versus "dramatic"; see later blog post). Busoni's Junge Klassizität also pushed in this direction, advocating an opera of "the masque and the supernatural." This "epic" conception is more or less the opposite of method acting, calling for an intellectual, critical stance toward the action, and a cold detachment from the emotions of the characters, allowing (especially in Brecht's formulation) theater to function as a tool of education, social critique, and propaganda more than as an emotionally absorbing entertainment, favoring satire and social commentary over romantic immersion, and rejecting any deep identification with individual fictional characters. The opera is set in Elizabethan England. The title character is an actor immersed in his art to the point where he loses touch with reality. The somewhat mediocre company of which he is part becomes to him something of a grand court theater, and he ultimately loses all separation between his real self and his character. During a rehearsal, mixing theatrical plot with reality, he murders his own beloved sister; coming somewhat back to his senses, he wishes only to be allowed to perform the actual play that evening and present this union of real and acted madness before an audience.

The staging of Der Protagonist was very unusual and innovative. There are two distinct orchestras: besides the full pit orchestra, a smaller onstage orchestra represents the musicians of a duke who has stopped at the inn where the players are resident, and who has requested a performance from them. Two pantomime sequences remain as traces of Kaiser and Weill's project as originally conceived two years earlier. Listening to the piece, a few things are quickly apparent: it is the work of an already mature composer; it is very much of its time (Alban Berg's Wozzeck was first performed while Der Protagonist was being written); and unlike the music that would make Weill truly world famous a few years later, Weill was not yet drawing on in any significant way on contemporary dance music and jazz. Oskar Bie wrote in a review after the premiere, "This is the pupil stepping beyond the master Busoni." Years later, Rainer Pömann would call Der Protagonist "astonishing" as a composer's first opera, "nowhere in it is there any sense of trial and error."

Jürgen Schebera writes in his Weill biography that Der Protagonist "combine[s] linear polyphony, atonal material, and penetrating chromaticism." My more formally musically trained friends don't seem to agree with one another on even the definition of linear polyphony, so I don't know whether Schebera had a single precise meaning in mind, but I can say that there are times when multiple musical "voices", sometimes even the literal voices of the singers, clash while each following their own melodic line. Sections of Der Protagonist could have come from a disciple of Schoenberg such as Berg, but there are certainly instrumental passages that would have been perfectly possible as early as the Eighteenth Century, which I think is not true of any eight consecutive bars of Schoenberg or Berg. I'll venture that Mozart would have found most of Der Protagonist disturbing but musically comprehensible. The piece as a whole maintains a discipline that clearly reflects Busoni's Junge Klassizität ("Young Classicalism"): characters may have strong emotions, but the orchestra does not.

Der Protagonist was a powerful culmination of Weill's early style. It established him as a composer to be reckoned with, but did not even hint at the fusion of classical and popular music that would characterize the next period of his work.

[This essay draws heavily on Jürgen Schebera's meticulously researched Kurt Weill: an illustrated life, (Yale, 1995, translated from the original German by Caroline Murphy).]

Next blog post: Transformation

Next Weill biography blog post: Transformation