By date

- 8 March 2021: Welcome!

- 9 March 2021: Kurt Weill and John Cale

- 18 March 2021: Happy Birthday, Kurt Weill!

- 26 March 2021: Working on "Mussel From Margate" and "Jealousy Duet"

- 03 April 2021: The Young Kurt Weill in Dessau

- 16 April 2021: Weill's Student years (1)

- 26 April 2021: Face-to-face!

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 20 May 2021: Novembergruppe

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 28 June 2021: Schickelgruber (song)

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 12 July 2021: What Is 'Epic Theater'?

- 15 July 2021: What Keeps Mankind Alive? (song)

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 25 July 2021: Speak Low (song)

- 2 August 2021: Youkali (song)

- 9 August 2021: François Villon

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 23 August 2021: Not exactly a manifesto

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 18 October 2021: Kurt Weill and shadow puppetry

- 25 October 2021: Summer 1933

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 8 November 2021: The Eternal Road

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 13 December 2021: One Touch of Venus

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 3 January 2022: Jewish Kurt Weill

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- 28 February 2022: Down in the Valley

- 14 March 2022: Love Life

- 28 March 2022: Lost in the Stars

Kurt Weill biography

- 03 April 2021: The Young Kurt Weill in Dessau

- 16 April 2021: Weill's Student years (1)

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 25 October 2021: Summer 1933

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 8 November 2021: The Eternal Road

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 13 December 2021: One Touch of Venus

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 3 January 2022: Jewish Kurt Weill

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- 28 February 2022: Down in the Valley

- 14 March 2022: Love Life

- 28 March 2022: Lost in the Stars

Lotte Lenya biography

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

By topic

- Agnes de Mille

- Alabama Song

- Alan Jay Lerner

- Alan Paton

- Arnold Sundgaard

- Baden-Baden

- Ben Hecht

- Berlin

- 16 April 2021: Weill's Student years (1)

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 20 May 2021: Novembergruppe

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- Berlin Im Licht

- Berliner Requiem

- Bertolt Brecht

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 12 July 2021: What Is 'Epic Theater'?

- 15 July 2021: What Keeps Mankind Alive? (song)

- 9 August 2021: François Villon

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- Broadway opera

- Caspar Neher

- Charles Lindbergh

- Complainte de la Seine

- Danny Kaye

- Darren Loucas

- David Drew

- Der Neinsager

- Der Protagonist

- Die Bürgschaft

- Down in the Valley

- Dresden

- East Portland Blog

- Elia Kazan

- Elisabeth Hauptmann

- Elmer Rice

- Engelbert Humperdinck

- Epic theater

- Erika Neher

- Erwin Piscator

- Eternal Road

- Expressionism

- Felix Jackson

- Firebrand of Florence

- Franz Werfel

- Frauentanz

- Fritz Busch

- Georg Kaiser

- George Antheil

- Georges Rouault

- Gertrude Lawrence

- Hannah Höch

- Hans Curjel

- Hollywood

- Hyperinflation

- Ira Gershwin

- Ivan Goll

- Jealousy Duet

- Jean Cocteau

- Jewish Kurt Weill

- Joe Mabel

- 8 March 2021: Welcome!

- 9 March 2021: Kurt Weill and John Cale

- 26 March 2021: Working on "Mussel From Margate" and "Jealousy Duet"

- 16 April 2021: Weill's Student years (1)

- 26 April 2021: Face-to-face!

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 20 May 2021: Novembergruppe

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 28 June 2021: Schickelgruber (song)

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 12 July 2021: What Is 'Epic Theater'?

- 15 July 2021: What Keeps Mankind Alive? (song)

- 25 July 2021: Speak Low (song)

- 2 August 2021: Youkali (song)

- 9 August 2021: François Villon

- 23 August 2021: Not exactly a manifesto

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 25 October 2021: Summer 1933

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 8 November 2021: The Eternal Road

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 13 December 2021: One Touch of Venus

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 3 January 2022: Jewish Kurt Weill

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- 28 February 2022: Down in the Valley

- 14 March 2022: Love Life

- 28 March 2022: Lost in the Stars

- Johann Gottfried Herder

- John Cale

- Juliana Brandon

- 8 March 2021: Welcome!

- 18 March 2021: Happy Birthday, Kurt Weill!

- 26 March 2021: Working on "Mussel From Margate" and "Jealousy Duet"

- 26 April 2021: Face-to-face!

- 28 June 2021: Schickelgruber (song)

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 25 July 2021: Speak Low (song)

- 2 August 2021: Youkali (song)

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 23 August 2021: Not exactly a manifesto

- 18 October 2021: Kurt Weill and shadow puppetry

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

- Kuhhandel

- Kurt Weill

- 8 March 2021: Welcome!

- 9 March 2021: Kurt Weill and John Cale

- 18 March 2021: Happy Birthday, Kurt Weill!

- 26 March 2021: Working on "Mussel From Margate" and "Jealousy Duet"

- 03 April 2021: The Young Kurt Weill in Dessau

- 16 April 2021: Weill's Student years (1)

- 26 April 2021: Face-to-face!

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 20 May 2021: Novembergruppe

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 28 June 2021: Schickelgruber (song)

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 12 July 2021: What Is 'Epic Theater'?

- 15 July 2021: What Keeps Mankind Alive? (song)

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 25 July 2021: Speak Low (song)

- 2 August 2021: Youkali (song)

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 23 August 2021: Not exactly a manifesto

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 18 October 2021: Kurt Weill and shadow puppetry

- 25 October 2021: Summer 1933

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 8 November 2021: The Eternal Road

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 13 December 2021: One Touch of Venus

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 3 January 2022: Jewish Kurt Weill

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- 28 February 2022: Down in the Valley

- 14 March 2022: Love Life

- 28 March 2022: Lost in the Stars

- Léo Lania

- Lüdenscheid

- Lady in the Dark

- Langston Hughes

- Lost in the Stars

- Lotte Lenya

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- Lotte Reiniger

- Love Life

- Lys Symonette

- Mahagonny

- Man Without Qualities

- Marc Blitzstein

- Marlene Dietrich

- Mary Martin

- Maurice Abravanel

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- Max Reinhardt

- Maxwell Anderson

- Meyer Weisgal

- Moss Hart

- Mussel From Margate

- Nazizeit

- New York

- One Touch of Venus

- Otto Dix

- Otto Pasetti

- Paris

- Princess du Polignac

- Robert Vambery

- Roger Fernay

- S.J. Perelman

- Scherenschnitte

- Schickelgruber

- Seven Deadly Sins

- Shadow puppetry

- Silbersee

- Street Scene

- Threepenny Opera

- Tilly Losch

- Weill Project

- 8 March 2021: Welcome!

- 9 March 2021: Kurt Weill and John Cale

- 18 March 2021: Happy Birthday, Kurt Weill!

- 26 March 2021: Working on "Mussel From Margate" and "Jealousy Duet"

- 26 April 2021: Face-to-face!

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 28 June 2021: Schickelgruber (song)

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 15 July 2021: What Keeps Mankind Alive? (song)

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 25 July 2021: Speak Low (song)

- 2 August 2021: Youkali (song)

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 23 August 2021: Not exactly a manifesto

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 18 October 2021: Kurt Weill and shadow puppetry

- 25 October 2021: Summer 1933

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 8 November 2021: The Eternal Road

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 13 December 2021: One Touch of Venus

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 3 January 2022: Jewish Kurt Weill

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- 28 February 2022: Down in the Valley

- 14 March 2022: Love Life

- 28 March 2022: Lost in the Stars

- Weill Project Blog

- Weill family

- Weill's Second Symphony

- What Keeps Mankind Alive

- What Was Sent to the Soldier's Wife

- World War II

- World War II propaganda

- Young Kurt Weill

- Yvette Endrijautzki

- Zeitoper

- degenerate art

Tags

#kurtweill #paulgreen #lottelenya #maxwellanderson #mauriceabravanel #newyork #hollywood #joemabel #weillproject #weillbio

(Prior biographical posts on Weill: [1],

[2],

[3],

[4],

[5],

[6],

[7],

[8],

[9],

[10],

[11],

[12],

[13],

[14],

[15],

[16],

[17],

[18].

Hollywood: "I have never seen so many worried and unhappy people together." - Kurt Weill

Photo by Tony Hisgett, licensed under CC-BY-2.0 🔗

Weill and Lenya married for the second time 19 January 1937, in a small ceremony north of the city in North Castle, New York. They didn't have much money, and besides supporting themselves, Weill now had his parents to support in Palestine. Weill's first Broadway play, Johnny Johnson, written with Paul Green had been neither a flop nor a true success; The Eternal Road, an enormous pageant on contemporary and Biblical Jewish themes—a collaboration with Franz Werfel, Max Reinhardt, and others—was a "hot ticket" but was on such a large scale that it never made money. Rather than any sort of honeymoon, Weill headed to Hollywood with Cheryl Crawford 🔗 of the Group Theatre, while Lenya borrowed Crawford's Beekman Place apartment with a view of the East River, and continued to sing the role of Miriam in The Eternal Road for the next several months.

Weill remained in Hollywood through June 1937. There he reconnected with other exiles. Director Fritz Lang 🔗 (Metropolis, M, and later Hangmen Also Die!) wanted to work with him, but had nothing immediate. He ended up working with William (Wilhelm) Dieterle 🔗 on a film about the Spanish Civil War, then still in raging. Originally The River is Blue, then Castles in Spain, and finally released in 1938 as Blockade, the film starred Henry Fonda. Weill got paid for his work, but the studio didn't think his music was accessible enough, and literally none of it got used; the film was eventually scored by Werner Janssen 🔗. Weill came back to New York a lot less interested in Hollywood, which he called "the craziest place in the world," adding "I have never seen so many worried and unhappy people together." Or, as he wrote to Cheryl Crawford, "Don't worry, Hollywood will not get to me. A whore never loves the man who pays her, she wants to get rid of him as soon as she has rendered her services. That is my relation to Hollywood. (I am the whore.)"

In August 1937, a few months after his return to New York, Weill and Lenya went briefly to Canada so that they could re-enter the U.S. as immigrants rather than visitors. They applied for citizenship 27 August 1937. It would finally be granted in 1943, though long before that they were calling themselves Americans.

While in Hollywood, Weill had been approached again by Ernst Josef Aufricht, the actor and theater manager crucial to the first production of Threepenny Opera, in Berlin. Aufricht was putting together a production of the play for the Paris World's Fair that summer, the Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne 🔗. Cabaret star Yvette Guilbert 🔗, then in her seventies, was to play Mrs. Peachum, and wanted more solos (normally, the only solo for the role is "The Ballad of Sexual Dependency"). Aufricht wrote lyrics for two songs and commissioned tunes from Weill, which Weill wrote on the basis that they were to be used solely for that production. According to Jürgen Schebera it is unclear if they were ever used; he says it is more likely that Guilbert wrote her own tunes.

So, more music written and never used. It seems that was to be the theme of the year. Back in New York, Weill plunged into the Federal Theater Project 🔗, but that was already facing headwinds in Congress over the perceived leftist and Communist content of so many of the plays. Under the auspices of the Federal Theater Project, he and Paul Green (with whom he had written Johnny Johnson the prior year, see previous blog post) began a play The Common Glory on early U.S. history; it never got out of the sketch stage. He then worked with Hoffman R. Hays on a musical version of Hays's play The Ballad of Davy Crockett, which got as far as a rehearsal script and songs, but was never properly finalized, as the Federal Theater Project began to collapse.

Fritz Lang got back to Weill in March 1938, asking him to work on the score for the You and Me 🔗, a supposedly "Brechtian" short story / fairy tale by screwball-comedy writer Norman Krasna 🔗. (This Brecht ist nicht so echt.) A department store owner hires ex-cons as a humanitarian gesture; they waver between going straight and robbing his store. Good triumphs, George Raft 🔗 marries Sylvia Sidney 🔗, etc. This time two Weill songs made it to the movie, but still the rest of his soundtrack was canned, and Lang largely ignored Weill's extensive ideas for how music could structure the film. At least he got well paid. The money was enough for Weill and Lenya to lease a house in Suffern, New York 🔗, about half an hour northwest of Manhattan.

Four of the five founders of the Playwrights' Company, photographed January 1939. Left to right: Maxwell Anderson 🔗, S.N. Behrman 🔗, Robert E. Sherwood 🔗, Elmer Rice 🔗.

Public domain because of non-renewal of copyright.

It's May 1938. Weill is back again from Hollywood. A year and a half earlier, he had two plays on Broadway, and was broke. Now, after a series of projects that basically went nowhere, his finances are looking up. Welcome to America.

And, oh, yeah, while Weill establishes himself in his new country, the Nazis take over Austria (12 March 1938) and in September they will roll into the Sudetenland of Czechoslovakia. America might be kind of crazy, but Europe was turning into a hell.

Back in 1935, Weill had met playwright Maxwell Anderson 🔗 through their mutual connection with the Group Theatre. Weill was certainly already aware of Anderson: in 1929, Weill's colleague Erwin Piscator had directed a German translation of Anderson's play What Price Glory 🔗 at the Theater in der Königgrätzer Straße under the German title Rivalen; around the same time, Anderson had written the screenplay for the film of Erich Maria Remarque's All Quiet on the Western Front 🔗. Remarque and Weill had moved in essentially the same circles in Berlin.

From the outset, Anderson and Weill had been inclined to collaborate on a play. Anderson had never written a musical, but wanted to try his hand at it. When Weill came back from Hollywood in May 1938, Anderson handed him a draft of Knickerbocker Holiday 🔗 (which they had previously discussed). And all of this was happening while a new production company was being formed: Anderson, S.N. Behrman 🔗, Sidney Howard 🔗, Elmer Rice 🔗, and Robert E. Sherwood 🔗, along with lawyer John F. Wharton 🔗, formed the Playwrights' Company 🔗 to produce their own plays. All had been previously associated in one or another degree with the Theatre Guild, but they wanted more autonomy. The company was launching with Sherwood's Abe Lincoln in Illinois, and they liked the prospect of following that with a musical.

Anderson and Weill spent the rest of the summer completing the piece, based loosely on Washington Irving's comic/satiric Knickerbocker's History of New York 🔗 (1809), probably the first work of political/historical satire written in the United States. There appears to have been quite a bit of haggling over the targets of their update of this satire. Anderson, a near-anarchist, was one of the few on the left with a visceral dislike of Franklin Roosevelt's "New Deal". Or perhaps a better word than "anarchist" is "libertarian": although Anderson certainly identified with the left, it is easy to see some of his views as more right-wing. About a month into the run of Knickerbocker Holiday, Anderson wrote a letter to the New York Times clarifying his political views and, in Stephen Hinton's word, taking a "belligerently libertarian stance," conflating the welfare state with Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia: "Men who are fed by their government will soon be driven down to the status of slaves or cattle."

The original draft of the play makes a Roosevelt ancestor into a tyrannical villain. Weill was willing to go as far as to have the Roosevelt ancestor be a rich man failing to get around to doing the right thing because of his own financial interests, but not to have him be so outright evil. Other Playwrights' Company members seem to have had similar compunctions. Elmer Rice would later write, "we did succeed, mainly by cajolery, in getting [Anderson] to delete some of the more pointed references to the New Deal." In the end, the 17th-century Roosevelt became a reasonably sympathetic character, and more of the ignominy was shifted onto the figure of the Dutch governor of New Amsterdam Peter Stuyvesant 🔗. Still, the satire cuts many directions: it certainly remains a strong attack on fascism as it existed in Europe, but with suggestions that some trends in America may not be so far from that. And even the villainous Stuyvesant gets one really great song, "September Song", an enormous hit at the time and which would later be the only song ever recorded by both Frank Sinatra and Lou Reed. (Reed recorded it at least twice. Here's my favorite. 🔗) The song was belatedly added for Walter Huston 🔗 as Stuyvesant: he'd never really gotten to sing a romantic song, and they decided to give him one. Again, Weill self-plagiarized music from one of his lesser-known works: the chorus is identifiably a rework of "Juans Lied" from Der Kuhhandel (a play I blogged about here).

Knickerbocker Holiday has a frame story about Washington Irving and a fourth-wall breaking ending in which Irving intervenes in the 17th-century story, advising Stuyvesant on how history will remember him if he does the right thing. It's a long play: there are 28 musical numbers; besides the aforementioned "September Song", some of you might be familiar with "It Never Was You" (here's Julie Andrews singing that with André Previn 🔗, starting at 1:20 and followed by another Weill song, "My Ship" from Lady in the Dark) and/or "How Can You Tell an American?" (here's a good version released roughly contemporaneously with the play 🔗, recorded under the name the "Radio City Four"). Although there are some rather jazzy numbers (such as "How Can You Tell an American?"), the play's 17th-century setting encouraged Weill to draw on a lot of less contemporary musical traditions. Stephen Hinton points out that some of the romantic songs recollect Viennese operetta, and critics at the time noticed that the political satiric songs often draw on the style of Gilbert and Sullivan. The play opened 19 October 1938 at the Ethyl Barrymore Theatre. Joshua Logan directed; longtime Weill associate Maurice Abravanel conducted. It received generally good reviews, and while some reviewers definitely criticized the play's anti-Roosevelt politics, they pretty much all agreed that Weill's music was excellent. "September Song" came in for particular praise. Much as with the "Moritat" ("Mack the Knife") in 1928, a late addition to a play became a hit. The play was a moderate financial success though not a smash, running for 168 performances. Contention had doubtless muddied the satire a little, but the play probably did better than if it had been a straight-out attack on FDR at the height of his popularity.

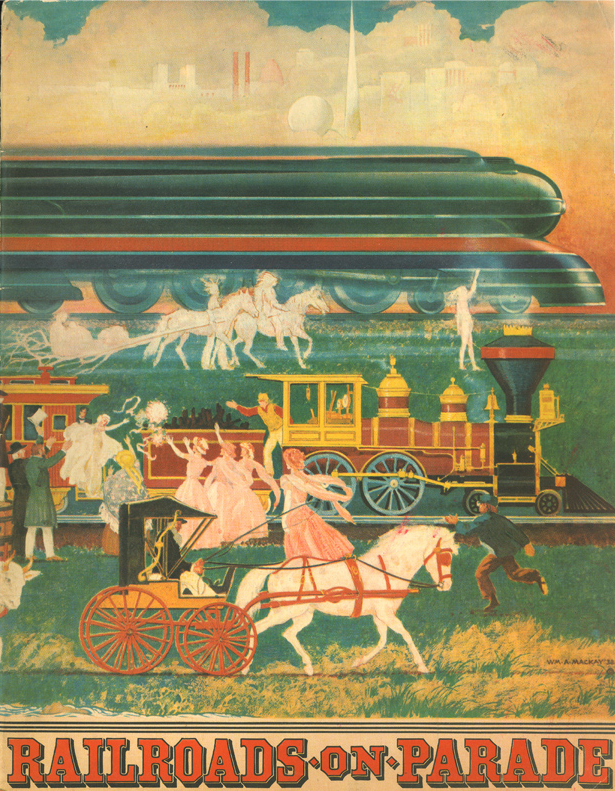

Souvenir book from "Railroads on Parade". Artist: William A. Mackay. 🔗

Believed to be public domain because of non-renewal of copyright.

Weill and Anderson started another project under the working title Ulysses Africanus, but Anderson had a lot of balls in the air and that work was never finished. Parts of it would resurface a roughly decade later, incorporated into the play Lost in the Stars.

Although not yet a citizen, Weill seemed to be finding his footing as an American composer. For the first time, he was writing songs that immediately found their way into the world of American popular music. He got a commission to write a 60-minute "circus opera" (as he called it), "Railroads on Parade" for the 1939 New York World's Fair. The piece, with lyrics by author and rail enthusiast Edward Hungerford 🔗, featured a chorus, orchestra, and fifteen historical locomotives. Weill's music quoted from colonial-era American songs, and the piece made musical use of the train whistles. This piece was the occasion for Weill's remark, "I have never acknowledged the difference between 'serious' music and 'light' music. There is only good and bad music."

In the next year or so, Weill wrote incidental music for two more Playwrights' Company productions, Madam, Will You Walk? by Sidney Howard and and Two on an Island by Elmer Rice. In 1940, Anderson and Weill wrote the radio cantata The Ballad of the Magna Carta, broadcast by CBS 4 February 1940. Weill would continue to work closely with Playwrights' Company members, and in 1946 would become the only member of the Playwrights' Company who was not, strictly speaking, a playwright.

[This essay draws heavily on Jürgen Schebera's meticulously researched Kurt Weill: an illustrated life, (Yale, 1995, translated from the original German by Caroline Murphy). I've also been influenced by Stephen Hinton's views on Knickerbocker Holiday, in his book Weill's Musical Theater: Stages of Reform (University of California, 2012).]

Next blog post: Lady in the Dark

Next Weill biography blog post: Lady in the Dark