By date

- 8 March 2021: Welcome!

- 9 March 2021: Kurt Weill and John Cale

- 18 March 2021: Happy Birthday, Kurt Weill!

- 26 March 2021: Working on "Mussel From Margate" and "Jealousy Duet"

- 03 April 2021: The Young Kurt Weill in Dessau

- 16 April 2021: Weill's Student years (1)

- 26 April 2021: Face-to-face!

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 20 May 2021: Novembergruppe

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 28 June 2021: Schickelgruber (song)

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 12 July 2021: What Is 'Epic Theater'?

- 15 July 2021: What Keeps Mankind Alive? (song)

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 25 July 2021: Speak Low (song)

- 2 August 2021: Youkali (song)

- 9 August 2021: François Villon

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 23 August 2021: Not exactly a manifesto

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 18 October 2021: Kurt Weill and shadow puppetry

- 25 October 2021: Summer 1933

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 8 November 2021: The Eternal Road

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 13 December 2021: One Touch of Venus

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 3 January 2022: Jewish Kurt Weill

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- 28 February 2022: Down in the Valley

- 14 March 2022: Love Life

- 28 March 2022: Lost in the Stars

Kurt Weill biography

- 03 April 2021: The Young Kurt Weill in Dessau

- 16 April 2021: Weill's Student years (1)

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 25 October 2021: Summer 1933

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 8 November 2021: The Eternal Road

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 13 December 2021: One Touch of Venus

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 3 January 2022: Jewish Kurt Weill

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- 28 February 2022: Down in the Valley

- 14 March 2022: Love Life

- 28 March 2022: Lost in the Stars

Lotte Lenya biography

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

By topic

- Agnes de Mille

- Alabama Song

- Alan Jay Lerner

- Alan Paton

- Arnold Sundgaard

- Baden-Baden

- Ben Hecht

- Berlin

- 16 April 2021: Weill's Student years (1)

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 20 May 2021: Novembergruppe

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- Berlin Im Licht

- Berliner Requiem

- Bertolt Brecht

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 12 July 2021: What Is 'Epic Theater'?

- 15 July 2021: What Keeps Mankind Alive? (song)

- 9 August 2021: François Villon

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- Broadway opera

- Caspar Neher

- Charles Lindbergh

- Complainte de la Seine

- Danny Kaye

- Darren Loucas

- David Drew

- Der Neinsager

- Der Protagonist

- Die Bürgschaft

- Down in the Valley

- Dresden

- East Portland Blog

- Elia Kazan

- Elisabeth Hauptmann

- Elmer Rice

- Engelbert Humperdinck

- Epic theater

- Erika Neher

- Erwin Piscator

- Eternal Road

- Expressionism

- Felix Jackson

- Firebrand of Florence

- Franz Werfel

- Frauentanz

- Fritz Busch

- Georg Kaiser

- George Antheil

- Georges Rouault

- Gertrude Lawrence

- Hannah Höch

- Hans Curjel

- Hollywood

- Hyperinflation

- Ira Gershwin

- Ivan Goll

- Jealousy Duet

- Jean Cocteau

- Jewish Kurt Weill

- Joe Mabel

- 8 March 2021: Welcome!

- 9 March 2021: Kurt Weill and John Cale

- 26 March 2021: Working on "Mussel From Margate" and "Jealousy Duet"

- 16 April 2021: Weill's Student years (1)

- 26 April 2021: Face-to-face!

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 20 May 2021: Novembergruppe

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 28 June 2021: Schickelgruber (song)

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 12 July 2021: What Is 'Epic Theater'?

- 15 July 2021: What Keeps Mankind Alive? (song)

- 25 July 2021: Speak Low (song)

- 2 August 2021: Youkali (song)

- 9 August 2021: François Villon

- 23 August 2021: Not exactly a manifesto

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 25 October 2021: Summer 1933

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 8 November 2021: The Eternal Road

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 13 December 2021: One Touch of Venus

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 3 January 2022: Jewish Kurt Weill

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- 28 February 2022: Down in the Valley

- 14 March 2022: Love Life

- 28 March 2022: Lost in the Stars

- Johann Gottfried Herder

- John Cale

- Juliana Brandon

- 8 March 2021: Welcome!

- 18 March 2021: Happy Birthday, Kurt Weill!

- 26 March 2021: Working on "Mussel From Margate" and "Jealousy Duet"

- 26 April 2021: Face-to-face!

- 28 June 2021: Schickelgruber (song)

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 25 July 2021: Speak Low (song)

- 2 August 2021: Youkali (song)

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 23 August 2021: Not exactly a manifesto

- 18 October 2021: Kurt Weill and shadow puppetry

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

- Kuhhandel

- Kurt Weill

- 8 March 2021: Welcome!

- 9 March 2021: Kurt Weill and John Cale

- 18 March 2021: Happy Birthday, Kurt Weill!

- 26 March 2021: Working on "Mussel From Margate" and "Jealousy Duet"

- 03 April 2021: The Young Kurt Weill in Dessau

- 16 April 2021: Weill's Student years (1)

- 26 April 2021: Face-to-face!

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 20 May 2021: Novembergruppe

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 28 June 2021: Schickelgruber (song)

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 12 July 2021: What Is 'Epic Theater'?

- 15 July 2021: What Keeps Mankind Alive? (song)

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 25 July 2021: Speak Low (song)

- 2 August 2021: Youkali (song)

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 23 August 2021: Not exactly a manifesto

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 18 October 2021: Kurt Weill and shadow puppetry

- 25 October 2021: Summer 1933

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 8 November 2021: The Eternal Road

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 13 December 2021: One Touch of Venus

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 3 January 2022: Jewish Kurt Weill

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- 28 February 2022: Down in the Valley

- 14 March 2022: Love Life

- 28 March 2022: Lost in the Stars

- Léo Lania

- Lüdenscheid

- Lady in the Dark

- Langston Hughes

- Lost in the Stars

- Lotte Lenya

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- Lotte Reiniger

- Love Life

- Lys Symonette

- Mahagonny

- Man Without Qualities

- Marc Blitzstein

- Marlene Dietrich

- Mary Martin

- Maurice Abravanel

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- Max Reinhardt

- Maxwell Anderson

- Meyer Weisgal

- Moss Hart

- Mussel From Margate

- Nazizeit

- New York

- One Touch of Venus

- Otto Dix

- Otto Pasetti

- Paris

- Princess du Polignac

- Robert Vambery

- Roger Fernay

- S.J. Perelman

- Scherenschnitte

- Schickelgruber

- Seven Deadly Sins

- Shadow puppetry

- Silbersee

- Street Scene

- Threepenny Opera

- Tilly Losch

- Weill Project

- 8 March 2021: Welcome!

- 9 March 2021: Kurt Weill and John Cale

- 18 March 2021: Happy Birthday, Kurt Weill!

- 26 March 2021: Working on "Mussel From Margate" and "Jealousy Duet"

- 26 April 2021: Face-to-face!

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 28 June 2021: Schickelgruber (song)

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 15 July 2021: What Keeps Mankind Alive? (song)

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 25 July 2021: Speak Low (song)

- 2 August 2021: Youkali (song)

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 23 August 2021: Not exactly a manifesto

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 18 October 2021: Kurt Weill and shadow puppetry

- 25 October 2021: Summer 1933

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 8 November 2021: The Eternal Road

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 13 December 2021: One Touch of Venus

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 3 January 2022: Jewish Kurt Weill

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- 28 February 2022: Down in the Valley

- 14 March 2022: Love Life

- 28 March 2022: Lost in the Stars

- Weill Project Blog

- Weill family

- Weill's Second Symphony

- What Keeps Mankind Alive

- What Was Sent to the Soldier's Wife

- World War II

- World War II propaganda

- Young Kurt Weill

- Yvette Endrijautzki

- Zeitoper

- degenerate art

Tags

#kurtweill #lottelenya #julianabrandon #weillproject #nannaslied #lenyabioOne of the songs I'm working on for the Weill Project is "Nannas Lied" (that's "Nanna's Song" for you non-German speakers). I find it to be the most beautiful of all of Weill's songs, vying with "Complainte de la Seine" and "Youkali". It's probably no coincidence that I also find it to be the most overtly Classical sounding. The story behind it as I hear it is that Brecht wrote the lyrics (which you can read here 🔗), borrowing heavily from François Villon as was his wont [ed. note: in this case, the line famously rendered into English by Dante Gabriel Rossetti 🔗 as "Where are the snows of yesteryear?" - JM], and Hanns Eisler 🔗 set the poem to music. You can hear his rendition here. [ed. note: Frankie Armstrong does a really fine version of Eisler's setting on the album Let No One Deceive You with Dave Van Ronk, but it doesn't currently appear to be on line. - JM] Kurt Weill heard Eisler's setting and felt moved enough by the poem that he wrote to Brecht and asked if he could also set the poem to music. Apparently Brecht consented and now we have Weill's beautiful and profoundly moving portrayal of the jaded life of a teenage prostitute.

Yes, that is Nanna, a presumably former prostitute because in the song she claims that "one can't stay seventeen forever," thus also stating that once one is no longer a teenager they are too old to even be a prostitute in 1920s Germany. In the first verse she sings of how she learned more bad than good on "the love market," but that is the game. In the second verse she sings of how it does eventually get easier, but you have to ration your feelings to be successful. In the third verse she sings that by the time you get used to converting lust into small change you find you're too old to be desired. The chorus thanks God that life all goes by so quickly, but not without some wistfulness for "the snows of last year," a line taken directly from Villon. Weill's music for the chorus highlights these contrasting feelings to great affect. It starts off with a sprightly dance rhythm as if Nanna really is glad that everything ends so quickly, but ends with sentimental yearning over the same.

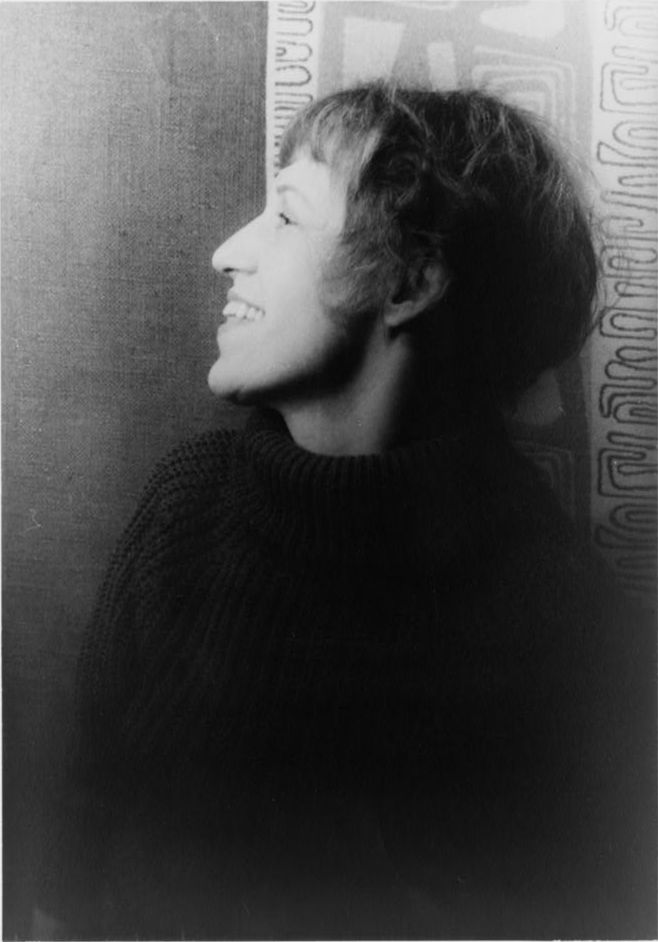

Lotte Lenya, photographed 1962 by Carl Van Vechten. (The Library of Congress believes this image is in the public domain; the Carl Van Vechten estate has asked reusers to "preserve the integrity" of Van Vechten's work, i.e, that photographs not be colorized or cropped, and Van Vechten be credited.)

Weill sounds practically Schubertian here in certain regards. The chorus makes use of what I call "the Viennese sigh" for lack of a better term, that rising stretched-out half step which seems to mourn moving on from such a beautiful note to yet another. It's also notable that among avant garde artists in the '20s and '30s Schubert's music was considered to be the height of bourgeois sentimentality, which could be another reason why Weill writes something so Schubertian to highlight the most sentimental lines of the poem. The similarity to Schubert in Weill's music was not lost on Lotte Lenya.

"She was always disturbed when Weill's songs were referred to as 'Cabaret Songs' and often stated that Weill never wrote a single song for the cabaret. She always referred to them as 'Art Songs' and felt that in their pure and simple wealth of melody they resembled Schubert songs more than any others." This is according to her friend Lys Symonette in the preface to The Unknown Kurt Weill—a collection of 14 songs as sung by Teresa Stratas. Symonette also claims that "Nannas Lied" was one of Lenya's very favorite songs written by Weill, which makes sense, not only because it was written as a birthday present for her, but it could also be about her.

We cannot really talk about Kurt Weill without talking about Lotte Lenya, not only his wife but his champion who acted as the textbook for Weill interpretation after his death. Her life before meeting him was every bit as colorful as it was horrifying.

Karoline Wilhelmine Charlotte Blamauer was born in 1898 to a tailor and a barmaid/laundress in Vienna. Perhaps Weill's hearkening back to Viennese classicism in "Nannas Lied" refers to her birthplace. As a child she was called Linnerl, which is the nickname of Karoline. Later, the famous Zurich director Richard Révy concocted the stage name Lotte Lenya (originally, in German, "Lenja"). Lotte comes from the Charlotte part of her name while Lenya is a Russianized bastardization of Linnerl. Lenya's life seemed cursed from the start. She was named Karoline after a former child who had died at age 2, a similar story to Vincent van Gogh and perhaps no less traumatizing for Lenya. The first Karoline was an especially beloved child because of her singing and dancing. Her father was so distraught after her death that he became a horrible alcoholic and tried to make Lenya a literal replacement for the dead daughter. Every night he would come home drunk, drag her out of bed, and make her sing and dance for him. When she wasn't good enough, which was every time, he would beat her, even throwing a lamp at her one night which nearly set her on fire. Lenya's sister, Maria, recalled that this type of brutal treatment was reserved especially for Linnerl who it seemed could do nothing in order to escape such abuse.

The Blamauer family was extremely poor and there must have been extreme pressure to bring in some kind of income as soon as possible, even for the children (in addition to Linnerl and Maria there was a son, Max.) Lenya was paid five cents a week for polishing the banister in her apartment building before she was even old enough to go to school. At one point in her childhood Lenya found some work singing and playing tambourine for a traveling circus who had befriended the family. She even learned how to walk the tightrope! In spite of all this hardship she excelled academically and was placed in a school for gifted children when she was ten. Even so, about a year later she "decided" to become a prostitute, something she claimed to have done because she wanted to even though it seems obvious that she felt enormous pressure from her family to earn something. An eleven year old does not just decide they want to become a prostitute.

Vienna around 1900, a view of The Graben. (Public domain.)

It was during her last years as a schoolgirl that she started learning the awful lessons of the love market which seemed to have left an indelible mark on her character. Love was now treated as a game even though it was something she yearned for deeply. Here she learned how to wrap a man around her finger to get anything she wanted, except for that love. Even Kurt Weill was always clear that his music came before her. [ed. note: In an interview late in life she recounted, with a slightly bitter laugh, him saying to her, "but dear, you know you come second after my music!", possibly completely unaware that was anything short of an entirely affectionate thing to say. - JM]

In the summer of 1913 Lenya's aunt Sophie came up to visit and decided she must have the girl to take back to Zurich as her own. Sophie's sister was delighted to have one less mouth to feed and sent her daughter off on a new adventure. The only caveat was that Sophie was the housekeeper for a retired doctor who didn't want anyone else sharing his home, so Lenya was hidden in a small room within the large house and kept a secret for several weeks. Sophie sadly realized she couldn't keep her, so she sent her off once more to live with some friends, The Ehrenzweigs, a professional photographer and his wife. This couple set Lenya up with her first dance lessons in classical ballet, Mrs. Ehrenzweig even made costumes for her recitals.

Zurich 1914, a postcard view of the new Urania Bridge. (Public domain.)

Lenya admitted she was no ballet dancer, but she found a niche for herself in free improvisation. Nonetheless she was good enough to land a role as a flower girl in Gluck's opera Orfeo at Zurich's Stadttheater. She was so excited about this that she showed up at six AM for a rehearsal that started at six PM! This began a succession of non-speaking roles in various operas. Even if Lenya never sang opera she at least gained quite a bit of knowledge about it.

Lenya returned to her family in Vienna in the summer of 1914 to find new horrors waiting for her. Her father had abandoned the family, such a pity, and her mother had already brought home someone else, and someone even worse! This man was also a violent alcoholic, but now it was Lenya's sister Maria who bore the brunt of his attacks, already looking gaunt and sickly when World War I broke out and the family was subjected to further food rationing. With the outbreak of the war Lenya knew she had to finagle a contract out of Zurich's Stadttheater in order to flee Austria for a more promising life in neutral Switzerland. She was successful, and her mother raised the train fare to get her back by taking advances from her customers on future laundry orders.

The war meant that theater roles weren't as plentiful as they used to be, but Lenya found work selling postcards and even managed to save enough to move out of the Ehrenzweigs' home to a place with her new friend Grete Edelmann's family. Lotte and Grete had many adventures and caused a lot of trouble together, but somehow managed to keep all this a secret from Grete's mother who insisted that her daughter was keeping her virtue for marriage even though Lotte recounted that Grete was always having one secret abortion after another. The pair could frequently be found living it up at one of Zurich's many nightclubs and cabarets, probably including the notorious Cabaret Voltaire 🔗.

Richard Révy, also known as Richard Ryen, seen here in the movie Casablanca in 1942. Yes, he was in Casablanca. Image used on a "fair use" basis.

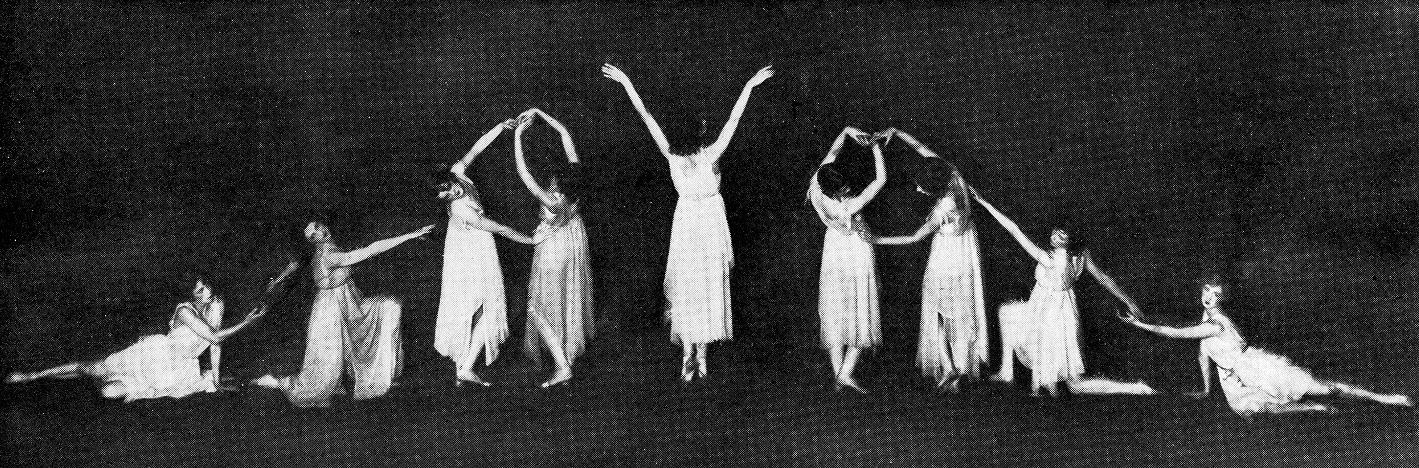

In 1915 the famous theater director Richard Révy became something of a father figure and took Lenya under his wing for private tutelage in drama and literature. This was when he renamed her, but at first she was Lotte Lenja. Lenja was anglicized to Lenya after she came to America. Révy was known mostly for directing the plays of Georg Kaiser, who would later become the link between Lenya and Weill (see prior blog post by Joe). Révy helped her get roles at Zurich's Schauspielhaus where throughout the rest of this wartime period Lenya continued to perform small non-speaking roles. However, she was also diversifying her understanding of dance by branching out into the new system started by Emile Jacques-Dalcroze 🔗 called eurythmics. Lotte and Grete frequently danced on stage together, including in a eurythmic presentation of a Johann Strauss waltz. It would also appear that the Stadttheater was progressive enough to present experimental dance pieces like this during the intermission of a more traditional staging of Strauss's Die Fledermaus.

By this time in 2021 we've all learned much more about the flu epidemic 🔗 of 1918 than we ever thought we would, and it turns out Lenya caught this particular plague and spent an entire month recovering, but once she did recover she was back out at the nightclubs in a heartbeat. It was on one such night shortly after her recovery that she met a rich bug-eyed Czech man who decided to have Lenya as his kept woman. In her words he had "…a condition that made his eyes stick out like two bubbles. But I got used to them the way I got used to the sudden wealth." The affair didn't last long though and Lenya, dripping with jewels, hooked up with a former lover, sculptor Mario Perucci, and with him went back to check on her family in Vienna in the summer of 1919.

Class in Dalcroze Eurythmics, Millikin College, 1927. At the time, this was a required course for their Public School Music degree. Photo from Millikin University site. Copyright status unknown as of 2021. Any surviving copyright will certainly expire January 1, 2023. Used on a fair use basis.

Her sister Maria was even sicker than when she last saw her, and her mother had been beaten so badly by her drunk boyfriend that she was in the hospital. Perucci leapt into action, arranging for Maria to come back with them to Zurich, and for their mother to recuperate with friends far away from her violent boyfriend. Maria ended up in a rest home in the Swiss mountains, but made a full recovery. The next time they went back to Vienna they found their mother well and the abuser behind bars.

Meanwhile, Lotte and Grete decided they wanted to make a fresh start in Berlin where Révy had told them the theater scene was doing some really revolutionary stuff. Through much of 1921 Grete and Lotte worked up a dance routine between the two of them to perform there, in Lenya's words, "It was a corny mishmash of classic ballet, Dalcroze, Isadora Duncan—you name it: Hungarian czardas, country waltzes and so forth." Révy's wife even made them costumes to take on the road. Lenya sold the jewels her Czech lover had given her, bought train tickets, and off she went with Grete to find fame in Berlin.

As for "Nannas Lied," you can hear Kurt

Weill's composition here 🔗 in two different versions (by Teresa Stratas and Ute Lemper, respectively).

For lots of rare photos of Lotte Lenya go to the Kurt Weill Foundation's website

here 🔗.

[This blog post borrows heavily from the book Lenya: A Life by Donald Spoto.]

Next blog post: Speak Low (song)

Next Lenya biography blog post: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera