By date

- 8 March 2021: Welcome!

- 9 March 2021: Kurt Weill and John Cale

- 18 March 2021: Happy Birthday, Kurt Weill!

- 26 March 2021: Working on "Mussel From Margate" and "Jealousy Duet"

- 03 April 2021: The Young Kurt Weill in Dessau

- 16 April 2021: Weill's Student years (1)

- 26 April 2021: Face-to-face!

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 20 May 2021: Novembergruppe

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 28 June 2021: Schickelgruber (song)

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 12 July 2021: What Is 'Epic Theater'?

- 15 July 2021: What Keeps Mankind Alive? (song)

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 25 July 2021: Speak Low (song)

- 2 August 2021: Youkali (song)

- 9 August 2021: François Villon

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 23 August 2021: Not exactly a manifesto

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 18 October 2021: Kurt Weill and shadow puppetry

- 25 October 2021: Summer 1933

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 8 November 2021: The Eternal Road

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 13 December 2021: One Touch of Venus

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 3 January 2022: Jewish Kurt Weill

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- 28 February 2022: Down in the Valley

- 14 March 2022: Love Life

- 28 March 2022: Lost in the Stars

Kurt Weill biography

- 03 April 2021: The Young Kurt Weill in Dessau

- 16 April 2021: Weill's Student years (1)

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 25 October 2021: Summer 1933

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 8 November 2021: The Eternal Road

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 13 December 2021: One Touch of Venus

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 3 January 2022: Jewish Kurt Weill

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- 28 February 2022: Down in the Valley

- 14 March 2022: Love Life

- 28 March 2022: Lost in the Stars

Lotte Lenya biography

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

By topic

- Agnes de Mille

- Alabama Song

- Alan Jay Lerner

- Alan Paton

- Arnold Sundgaard

- Baden-Baden

- Ben Hecht

- Berlin

- 16 April 2021: Weill's Student years (1)

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 20 May 2021: Novembergruppe

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- Berlin Im Licht

- Berliner Requiem

- Bertolt Brecht

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 12 July 2021: What Is 'Epic Theater'?

- 15 July 2021: What Keeps Mankind Alive? (song)

- 9 August 2021: François Villon

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- Broadway opera

- Caspar Neher

- Charles Lindbergh

- Complainte de la Seine

- Danny Kaye

- Darren Loucas

- David Drew

- Der Neinsager

- Der Protagonist

- Die Bürgschaft

- Down in the Valley

- Dresden

- East Portland Blog

- Elia Kazan

- Elisabeth Hauptmann

- Elmer Rice

- Engelbert Humperdinck

- Epic theater

- Erika Neher

- Erwin Piscator

- Eternal Road

- Expressionism

- Felix Jackson

- Firebrand of Florence

- Franz Werfel

- Frauentanz

- Fritz Busch

- Georg Kaiser

- George Antheil

- Georges Rouault

- Gertrude Lawrence

- Hannah Höch

- Hans Curjel

- Hollywood

- Hyperinflation

- Ira Gershwin

- Ivan Goll

- Jealousy Duet

- Jean Cocteau

- Jewish Kurt Weill

- Joe Mabel

- 8 March 2021: Welcome!

- 9 March 2021: Kurt Weill and John Cale

- 26 March 2021: Working on "Mussel From Margate" and "Jealousy Duet"

- 16 April 2021: Weill's Student years (1)

- 26 April 2021: Face-to-face!

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 20 May 2021: Novembergruppe

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 28 June 2021: Schickelgruber (song)

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 12 July 2021: What Is 'Epic Theater'?

- 15 July 2021: What Keeps Mankind Alive? (song)

- 25 July 2021: Speak Low (song)

- 2 August 2021: Youkali (song)

- 9 August 2021: François Villon

- 23 August 2021: Not exactly a manifesto

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 25 October 2021: Summer 1933

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 8 November 2021: The Eternal Road

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 13 December 2021: One Touch of Venus

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 3 January 2022: Jewish Kurt Weill

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- 28 February 2022: Down in the Valley

- 14 March 2022: Love Life

- 28 March 2022: Lost in the Stars

- Johann Gottfried Herder

- John Cale

- Juliana Brandon

- 8 March 2021: Welcome!

- 18 March 2021: Happy Birthday, Kurt Weill!

- 26 March 2021: Working on "Mussel From Margate" and "Jealousy Duet"

- 26 April 2021: Face-to-face!

- 28 June 2021: Schickelgruber (song)

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 25 July 2021: Speak Low (song)

- 2 August 2021: Youkali (song)

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 23 August 2021: Not exactly a manifesto

- 18 October 2021: Kurt Weill and shadow puppetry

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

- Kuhhandel

- Kurt Weill

- 8 March 2021: Welcome!

- 9 March 2021: Kurt Weill and John Cale

- 18 March 2021: Happy Birthday, Kurt Weill!

- 26 March 2021: Working on "Mussel From Margate" and "Jealousy Duet"

- 03 April 2021: The Young Kurt Weill in Dessau

- 16 April 2021: Weill's Student years (1)

- 26 April 2021: Face-to-face!

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 20 May 2021: Novembergruppe

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 28 June 2021: Schickelgruber (song)

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 12 July 2021: What Is 'Epic Theater'?

- 15 July 2021: What Keeps Mankind Alive? (song)

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 25 July 2021: Speak Low (song)

- 2 August 2021: Youkali (song)

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 23 August 2021: Not exactly a manifesto

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 18 October 2021: Kurt Weill and shadow puppetry

- 25 October 2021: Summer 1933

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 8 November 2021: The Eternal Road

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 13 December 2021: One Touch of Venus

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 3 January 2022: Jewish Kurt Weill

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- 28 February 2022: Down in the Valley

- 14 March 2022: Love Life

- 28 March 2022: Lost in the Stars

- Léo Lania

- Lüdenscheid

- Lady in the Dark

- Langston Hughes

- Lost in the Stars

- Lotte Lenya

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- Lotte Reiniger

- Love Life

- Lys Symonette

- Mahagonny

- Man Without Qualities

- Marc Blitzstein

- Marlene Dietrich

- Mary Martin

- Maurice Abravanel

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- Max Reinhardt

- Maxwell Anderson

- Meyer Weisgal

- Moss Hart

- Mussel From Margate

- Nazizeit

- New York

- One Touch of Venus

- Otto Dix

- Otto Pasetti

- Paris

- Princess du Polignac

- Robert Vambery

- Roger Fernay

- S.J. Perelman

- Scherenschnitte

- Schickelgruber

- Seven Deadly Sins

- Shadow puppetry

- Silbersee

- Street Scene

- Threepenny Opera

- Tilly Losch

- Weill Project

- 8 March 2021: Welcome!

- 9 March 2021: Kurt Weill and John Cale

- 18 March 2021: Happy Birthday, Kurt Weill!

- 26 March 2021: Working on "Mussel From Margate" and "Jealousy Duet"

- 26 April 2021: Face-to-face!

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 28 June 2021: Schickelgruber (song)

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 15 July 2021: What Keeps Mankind Alive? (song)

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 25 July 2021: Speak Low (song)

- 2 August 2021: Youkali (song)

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 23 August 2021: Not exactly a manifesto

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 18 October 2021: Kurt Weill and shadow puppetry

- 25 October 2021: Summer 1933

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 8 November 2021: The Eternal Road

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 13 December 2021: One Touch of Venus

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 3 January 2022: Jewish Kurt Weill

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- 28 February 2022: Down in the Valley

- 14 March 2022: Love Life

- 28 March 2022: Lost in the Stars

- Weill Project Blog

- Weill family

- Weill's Second Symphony

- What Keeps Mankind Alive

- What Was Sent to the Soldier's Wife

- World War II

- World War II propaganda

- Young Kurt Weill

- Yvette Endrijautzki

- Zeitoper

- degenerate art

Tags

#kurtweill # #jewishkurtweill #benhecht #joemabel #weillproject #weillbio

(Prior biographical posts on Weill: [1],

[2],

[3],

[4],

[5],

[6],

[7],

[8],

[9],

[10],

[11],

[12],

[13],

[14],

[15],

[16],

[17],

[18],

[19],

[20],

[21],

[22].

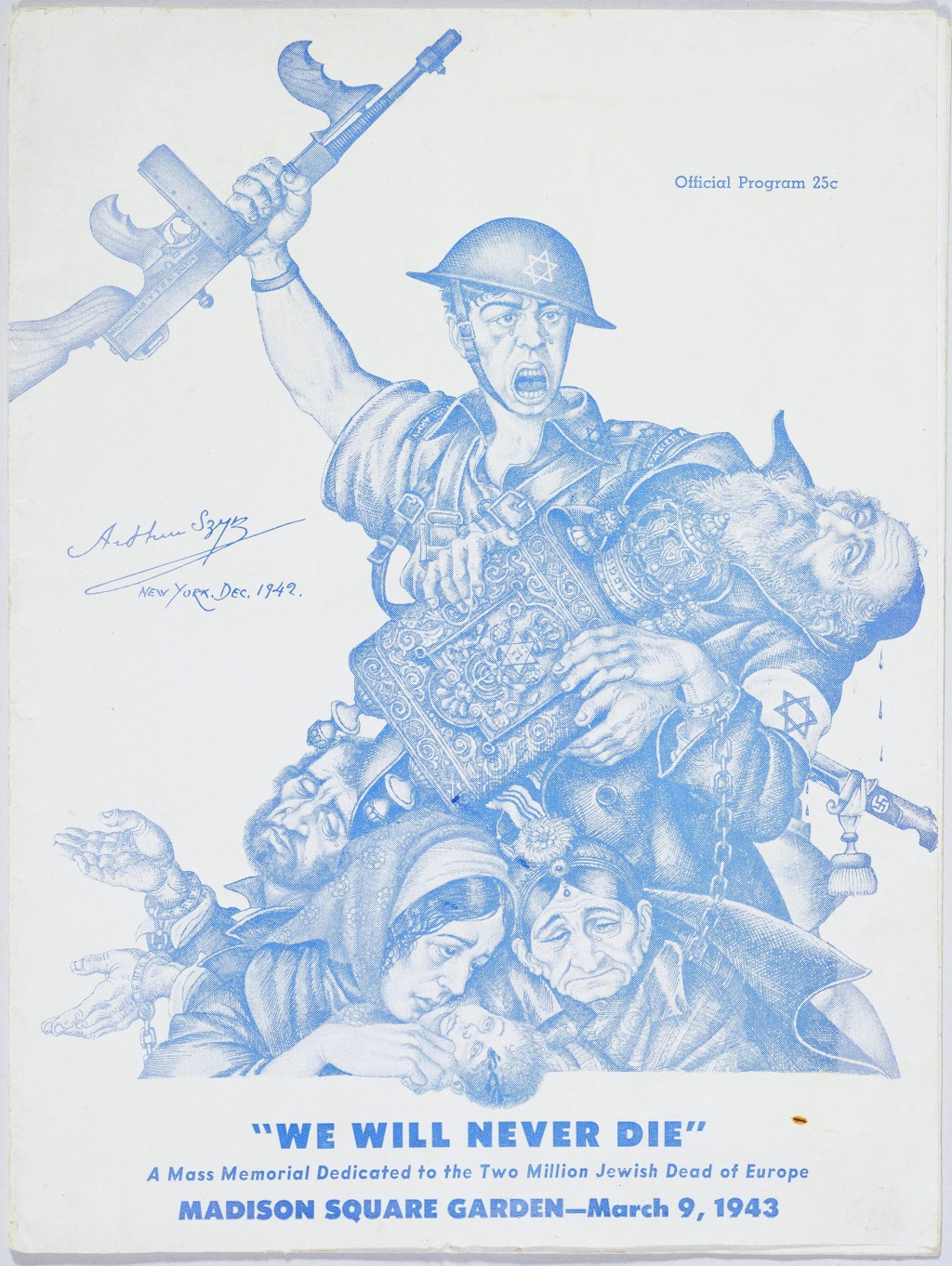

The program for the 1943 pageant We Will Never Die at Madison Square Garden features the artwork "Tears of Rage" by

the Polish-Jewish artist Arthur Szyk 🔗.

Copyright status unclear, used on a "fair use" basis.

Last time, discussing Weill's propaganda work during World War II, I mentioned Ben Hecht's 🔗 pageant play We Will Never Die 🔗, an effort to call public attention to the plight of Europe's Jews, and said we'd get back to that in the context of Weill's specifically Jewish projects in the 1940s. In fact, I'm going to expand that context and start with a recap, because this was hardly the first time Jewish themes figured prominently in Weill's work.

As I wrote in my first biographical post on Weill, Kurt Weill was the son of an Orthodox Jewish cantor, but he himself became very secular, probably by the time he was old enough to have an opinion of his own and certainly by early adulthood, although down to the age of 23 he continued to set some specifically Jewish texts to music. There were plenty of other secular, ethnic Jews among his circle in 1920s and early 1930s Germany, but, other than his relationship with his family, he doesn't seem to have had any particular attachment to the Jewish community as such until the rise of the Nazis drove him, his family, and so many other Jews from Germany. As this piece will show, from that point on specifically Jewish pieces (most of them Zionist rather than religious as such) make up a significant, though certainly secondary, stream in his work.

Repeating again from that earlier blog post, Weill's father Albert Weill (1867–1950) was an Orthodox cantor in a synagogue in Dessau, and was a musically and culturally progressive man and a fairly good composer in his own right. Weill's mother Emma Weill (née Ackermann; 1872–1955) was an intellectual with a large library. The Weills could trace back their family history in Germany to 1360, five hundred years before the founding of the modern German state. They lived in Dessau's largely Jewish "Sandvorstadt", but Weill attended public school and most of his friends and classmates were Protestant, one of them son of a Protestant minister. Even as Weill himself became increasingly secular, he remained in no small measure culturally Jewish: probably the most important early work of his that survives (salvaged by his sister Ruth) is Ofrahs Lieder, a setting of five Hebrew-language poems by the 12th-century Sephardic Jew Jehuda Halevi. Weill wrote this at the age of 16. Here's a performance (on YouTube) by Sharon Azrieli with the Israel Chamber Orchestra 🔗. (Just an aside: even in this work of his teenage years, you can hear some distinctly "Weillian" touches. Listen for a few measures at 3:11, or at about 4:39 where the song "Er kusste..." begins.)

In April 1918 Kurt Weill arrived at the Staatliche Hochschule für Musik in Berlin, a school that would ultimately disappoint him. The life of Berlin, though, including in the heady days of the Sparticist uprising, he liked. He regularly attended plays, concerts, opera, and so forth, which he could afford because he was working as choir director of a synagogue in Berlin-Friedenau. Most of the choir members (including all of the men) were Gentiles and, by Weill's account, not very dedicated; this taskmaster-conductor job was not much fun but, along with an academic stipend it definitely paid the bills; it would be many years before Weill had that kind of money again.

But at the end of World War I, Germany's economy was doing poorly. Weill's studies were interrupted when the congregation at his father's synagogue could no longer afford to pay a cantor. Albert Weill was laid off in the summer of 1919. For the next year, Kurt Weill supported the family by a series of jobs, most notably as conductor/arranger job at what Jürgen Schebera describes as a "third-rate theater" in Lüdenscheid (more about this in a prior blog post). Somehow he found time to do some composing that year, including Sulamith, a choral fantasy based on the Biblical Song of Songs, which was eventually performed, but only part of which survives. In any case, his father eventually got a job running a Jewish orphanage in Leipzig, and Weill returned to Berlin and eventually to his studies, this time in a master class taught by Ferruccio Busoni 🔗.

For the most part, Weill's life for the next decade or so had little to do with the Jewish community. His final project for Busoni is pretty much the last of his pieces before his emigration to be rooted in a Jewish text: Recordare: Klage lieder Jeremaiae V. Kapitel (Recordare: Lamentations of Jeremiah, Chapter 5), an a capella choral piece based on Old Testament texts. Considered unperformable at the time, it finally premiered in 1971 at the Holland Festival. By this time, Weill was drawing close to the leftist artist's organization known as the Novembergruppe. He would collaborate with a number of key figures in Weimar-era German theater, including Georg Kaiser 🔗 and (probably most notably) Bertolt Brecht 🔗, with whom he would write what is generally seen as his (and, quite likely, Brecht's) most important work, the Dreigroschenoper (Threepenny Opera). Through Kaiser, he met and married (and divorced, and remarried) Lotte Lenya 🔗. In his three years of working closely with Brecht (1927-1930), Weill would move decisively from the world of the concert hall to that of the theater, and performing their works would make Lenya a star in her own right. While the Nazis might have claimed that there was a specifically Jewish aspect to Weill's avant garde music of those years, part of the so-called "degenerate art 🔗" that they denounced and banned once in power, it's no more specifically Jewish than, say, the work of Burt Bacharach, Carole King, or Amy Winehouse, to pick some more recent examples.

By the time the Nazis took over Germany, Weill was more or less the country's most celebrated composer of theater music, but he exemplified everything they opposed. The February 1933 opening of his and Kaiser's Wintermärchen ("winter's tale") Silbersee ("The Silver Lake") was Germany's last great cultural gathering before Nazi rule consolidated itself. Then came the Reichstag Fire, and within a month Weill was in Paris, never to set foot in Germany again. The rest of his family would eventually escape to the British Mandate of Palestine, the future Israel.

For the most part, Weill's existence in Paris the next couple of years was no more specifically Jewish than his life in Berlin had been. Of course there were an enormous number of Jews among those who had rapidly fled Germany on Hitler's ascent to power, but also anybody left of a certain point on the political spectrum had plenty of reason to leave, as did anyone who was at all a cultural radical. One project, though, brought him back toward his Jewish roots, and it was also the project that brought him to America.

I've already written at some length about the pageant that became The Eternal Road, so I'm going to limit my recapitulation here. The Eternal Road had initial funding from several American Jewish organizations. Meyer Weisgal 🔗, head of the Zionist Organization of America, reached out to producer-director Max Reinhardt 🔗 in November 1933 in Paris. Reinhardt brought in Franz Werfel 🔗 as librettist and Weill as composer. Weisgal would later write of their meeting at Schloss Leopoldskron, Reinhardt's residence near Salzburg, Austria, "three of the best-known un-Jewish Jewish artists, gathered in the former residence of the Archbishop of Salzburg, in actual physical view of Berchtesgaden, Hitler's mountain chalet across the border in Bavaria, pledged themselves to give high dramatic expression to the significance of the people they had forgotten about till Hitler came to power."

The collaboration was not an easy one. Werfel wanted a straight play with incidental music, Weill wanted something more like an opera or oratorio. Along the way, versions of the piece were as long as roughly six hours, before finally settling into something a bit more manageable. And by the time the piece finally opened—years later—in New York, Norman Bel Geddes's grandiose set design meant that even with great reviews and packed houses, it lost money. But it did get Weill to New York, and more importantly for our topic here, it got him to turn back to specifically Jewish music for the first time in over a decade. The structure of the piece was to alternate between scenes set in a synagogue in a time of pogroms and Biblical scenes, with the two finally merging at the end as the destruction of the synagogue became one with the destruction of the Temple. Weill decided that the synagogue scenes should draw on specifically Jewish traditional music. He wrote down all of the specifically Jewish tunes and motifs he knew from his youth—several hundred of them—and then researched to find which of these predated the Englightenment and were therefore least likely to have incorporated modern, non-Jewish sources. As he wrote, he wished to avoid music that had borrowed from "opera, 'hit-songs' of the time, street tunes, concert music, symphonies." The result was generally deemed an artistic success, though a financial failure.

Musically, Weill's setting of Ben Hecht's 1943 pageant play We Will Never Die 🔗 followed the pattern of The Eternal Road. This new pageant was an effort in 1943 to call public attention to the plight of Europe's Jews: already at that time the best estimate was that the war had caused two million civilian Jewish deaths. As with The Eternal Road, We Will Never Die drew on Jewish folk music and alternated large choral scenes with smaller scenes. The piece was divided into four sections: "The Roll Call" spanned centuries of Jewish history; "The Jew in War" honored Jewish soldiers in the various Allied armies, especially the American and Soviet armies; "The Battle of Warsaw" celebrated the then very recent Warsaw Ghetto Uprising 🔗; and, finally, "Remember Us" was dedicated to the victims of the ghettos and concentration camps. Weill recycled some of his music from The Eternal Road, and grabbed a great deal of other suitable and available music: fanfares, patriotic songs of various countries, etc. The sequence about the then very recent Warsaw Ghetto Uprising 🔗 even used some fragments of Nazi music, countered by the Zionist anthem "Hatikvah 🔗" (later the national anthem of Israel) and the Polish patriotic song "Warszawianka 🔗". Isaac van Grove, who had conducted The Eternal Road throughout its Broadway run and who had also worked with Weill on Railroads on Parade for the 1939 New York World's Fair, conducted; he probably had a larger role in arranging the music than that word normally suggests (and certainly also functioned as a choirmaster, etc.)

The pageant was first performed 9 March 1943 at Madison Square Garden. It included several Jewish prayers, in which numerous rabbis and cantors (some sources say twenty, others say as many as 200) participated on stage. An enormous number of prominent figures from stage and screen, most of them Jewish, either acted roles or participated in the narration. According to Wikipedia, these included Edward G. Robinson 🔗, Sam Levene 🔗, Paul Muni 🔗, Joan Leslie 🔗, Katina Paxinou 🔗, Sylvia Sidney 🔗, Edward Arnold 🔗, John Garfield 🔗, Paul Henreid 🔗, Jacob Ben-Ami 🔗, Blanche Yurka 🔗, J. Edward Bromberg 🔗, Akim Tamiroff 🔗, Roman Bohnen 🔗, Art Smith 🔗, Helene Thimig 🔗, Shimen Ruskin and Leo Bulgakov, and also a few rather prominent Gentiles: Ralph Bellamy 🔗, Frank Sinatra 🔗 and Burgess Meredith 🔗. Billy Rose 🔗 and Ernst Lubitsch 🔗 functioned as producers; Moss Hart 🔗 handled the staging.

Demand for tickets was high enough that even with a capacity of about 40,000 the performance was repeated the following day, and then (with different but overlapping casts) in Washington, D.C, Philadelphia, Chicago, Boston, and finally at the Hollywood Bowl. There were several radio broadcasts; the culminating Hollywood Bowl performance 21 July 1943 was broadcast nationally on NBC. A fairly decent (but certainly not high-fidelity) recording of that broadcast survives and thanks to the Burgess Meredith Legacy YouTube Channel it is available on YouTube. It is not known how closely the performances in the various cities conformed to one another. The performance materials are lost, so that recording is presumably the best documentation remaining.

We Will Never Die at the Hollywood Bowl 21 July 1943 (NBC radio broadcast)

Hecht, and through him Weill, was affiliated with the so-called Bergson Group that centered around Hillel Kook 🔗, who was known in America as Peter Bergson. This group was firmly in the camp of the more militant (some say terrorist) and territorially maximalist Revisionist Zionism 🔗, as against the then-dominant Labor Zionism 🔗. Given Weill's generally socialist politics, I find that a somewhat surprising alignment for him. It might have been the Bergson Group's emphasis on helping Jews get out of Europe to Palestine; it might simply have had more to do with who he knew socially and professionally than with specific conviction on his part; I will readily admit that I'm pretty ignorant about the details of this. Edna Nahshon points out that although more mainline Zionists such as Dr. Stephen Wise ardently opposed the Bergson Group, their endorsers at one time or another included—besides the many people involved in We Will Never Die—first lady Eleanor Roosevelt, former president Herbert Hoover, California governor and future Supreme Court justice Earl Warren, the Hearst newspaper organization, Dorothy Parker, and Langston Hughes, not to mention Thomas Mann and Weill's onetime collaborator Lion Feuchtwanger, as well as Groucho and Harpo Marx.

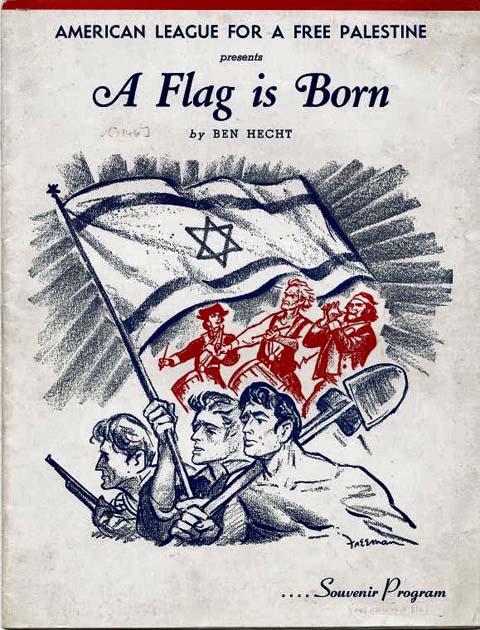

In 1946 Weill and Hecht collaborated again, this time on something closer to a proper stage play, a bit less of a pageant. Unlike We Will Never Die, presented at venues like Madison Square Garden and the Hollywood Bowl, A Flag is Born 🔗 ran for fifteen weeks in Broadway theaters, (first in September 1946 at the Alvin Theatre and then three other theaters: no one anticipated such a long run and they had not made a long-term booking), before touring to Chicago, Detroit, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Boston; there was a further tour to South America. This was not a musical; Weill provided incidental music, and there is extensive liturgical music in a synagogue scene, and "Hatikvah" is sung at the end. Little of Weill's incidental music survives. Once again Isaac van Grove conducted, and this time he is overtly credited as an arranger. I honestly don't know whether the music has been preserved; I've certainly never heard it. The play was intended as a benefit for Hillel Kook's organization known as the American League for a Free Palestine. With many, including Hecht, Weill, director Luther Adler 🔗, and several cast members choosing to work for no pay, this play actually did raise a great deal of money for its cause. Over the course of performances in six North American cities raised $400,000 for that organization, an enormous sum in that era, comparable to nearly six million dollars in 2021.

The program for the 1946 pageant play A Flag Is Born features artwork by an artist credited only as Tassman. The image clearly draws an analogy between the Jewish soldiers of the Haganah and Irgun, and the Continental soldiers of the American Revolution.

Copyright status unclear, used on a "fair use" basis.

With A Flag is Born, Weill's career intersected (not for the first time) with America's most prominent Jewish theater family, the Adlers. Jacob Alder 🔗 (1855-1926) had been the leading star of serious Yiddish-language theater, first in Russia, then in London, and finally in New York. He was among the first to commission serious original dramatic works in Yiddish, and he himself translated Tolstoy's Living Corpse into Yiddish and presented it on the stage. He was the first person to stage Ibsen in New York (in Yiddish, of course) and even was performing Shaw's plays, in Yiddish translation, in New York before they had ever appeared there in the original English. He founded quite a theatrical dynasty, including the director of A Flag is Born, Luther Adler; its female lead, Celia Adler 🔗; and Stella Adler 🔗, who like Luther had been associated with the Group Theatre 🔗, one of the first companies with whom Weill had worked in America. Stella Adler, one of the few Americans ever to study directly under Konstantin Stanislavski 🔗, inventor of "method acting". By this time, Stella Adler was mainly a teacher, and one of her prize pupils, the young Marlon Brando 🔗 had one of his breakthrough roles in this play. Two years later, he would play Stanley Kowalski in the Broadway production of A Streetcar Named Desire.

A Flag is Born was somewhere between a propaganda piece and a normal stage play. Edna Nahshon, who has written extensively on Jewish theater, described it as "resembl[ing] a medieval morality play." The play began with a narration by war correspondent Quentin Reynolds 🔗, playing himself. The image presented was, as Nahshon eloquently puts it 🔗:

For non-Jews, post-war Europe pulsated with the promise of rebirth, with the energy of new businesses, with new dreams "hatching in the debris of cities." However, for the Jew, Europe was a wasteland, a world without streets or faces, a gallows and a limepit with dead relatives lying under every road, its landscape transformed by the Holocaust into a garden of hell whose brooks and rivers emitted the wails of murdered Jewish infants.

All three major characters are survivors of the concentration camps, trying to get to Palestine. An older couple, Tevya (actor Paul Muni 🔗) and Zelda (Celia Alder) and an angry young man (Brando) seek overnight shelter in a graveyard. Zelda realizes that it is Sabbath evening, and they manage to do the rituals of Sabbath there, in a graveyard, a place practicing Jews would never normally enter on the Sabbath. A large portion of the play then follows Tevya's dreams that night (and one of Zelda's dreams), which give the framework for more of a pageant. Successively, we see a service in the synagogue in Tevya's native shtetl, show with a splendor that presumably outstrips any likely reality. Then we have a dream of King Saul before the battle of Yabesh Gilead, and of King David as psalmist. Zelda's dream, of a Shabbat meal at home with all their children is then narrated, but not enacted. Tevya then dreams of King Solomon and Temple, and Solomon encourages Tevya to lay his plight before the Council of the Mighty, which Nahshon describes as "a bitter parody of the Security Council of the newly formed United Nations." Tevya's speech is simple but powerful, but of course the Council are unswayed. Worst among them are the British representatives, who are portrayed as being little different from Nazis.

At this point, dream and reality merge again: young David, who has heard Tevya's speech and seen the Council's reaction, mocks him for coming to the mighty like a beggar. Tevya sees that Zelda has died in the night. Tevya recites the Kaddish (the Jewish prayer for the dead) and sees the angel of death coming to take him as well. His dying wish is for David to go on, but David at this point feels defeated and suicidal. Just before he is about to stab himself in the heart, three Jewish soldiers (real? imaginary? who knows) appear and urge him to follow them to Jerusalem. He follows them, and the play ends with them crossing a bridge, singing the "Hatikvah". David, ready to fight, makes his way out of the graveyard of Europe.

At one point in the play, David speaks at the American and presumably largely Jewish audience with a bitterness that is almost unimaginable in a play that was intended to win anyone over, but there it is:

Where were you—Jews [of America and England] when the killing was going on? When the six million were burned and buried alive in the lime pits, where were you? Where was your voice crying out against the slaughter? We didn't hear any voice. There was no voice. … A curse on your silence! … You with your Jewish hearts hidden behind English accents—you let the six million die—rather than make the faux pas of seeming a Jew. We heard—your silence—in the gas chambers. …

As noted above, little of Weill's music for A Flag is Born survives. It was definitely a side project for him: he was deep in writing Street Scene at the time. According to Christian Kuhnt, we're left with a piano-vocal reduction (probably not Weill's own) for four numbers ("Opening", "Partisan", "No. 13 Temple Music", and "#14 Interlude", the last of these incomplete), various very partial evidence of other pieces (e.g. for one song we have only the drum and bass parts, for another just the trombone) and some notes about the music in Luther Adler's directing script. I've never seen or heard any of this; I'm just summarizing what I've read, mainly in the Spring 2002 Kurt Weill Newsletter. We know that the play started with Weill's earlier music of the scene of the destruction of the Temple in The Eternal Road, which also recurs in "No. 13 Temple Music". There were further borrowings from The Eternal Road, We Will Never Die, liturgical music, and Yiddish folk song. An original song, "The Partisan", played as David first comes on the scene, begins as a tango and evolves into a march. Again, as in A Flag is Born, there were fanfares at certain key points. King David in Tevya's dream apparently sang Psalm 23 ("The Lord is my shepherd…"). Zelda's dream of a family Shabbat was accompanied by the Yiddish song "Rozhinkes mit Mandlen", presumably in the 1880 version by Abraham Goldfaden 🔗, the father of Yiddish theater. The Council of the Mighty scene used a pastiche of Gilbert and Sullivan's "Punishment to Fit the Crime", George M. Cohan's "Give My Regards to Broadway", "The Marseillaise,", a "Russian March" and probably other songs identified with other nationalities. And, of course, there was the "Hatikvah", the Kaddish (presumably in the same arrangement as in We Will Never Die), and a few other themes or pieces that seem to be entirely lost, or for which we have only a few random surviving instrumental parts.

In short, whereas Weill approached The Eternal Road with as much ambition as was characteristic of his major works for the stage, We Will Never Die and A Flag is Born were not ambitious pieces of work for Weill. The Eternal Road, despite him constantly referring to it in his correspondence with Lenya as "that Bible thing", was an important project that helped him establish himself in the theatrical world outside Germany. As it turned out, it was key to his building a reputation in a new land, America. We Will Never Die and A Flag is Born were more of a political act, doubtless sincere, and solidly workmanlike, but not central to his art. In both of the latter cases, the music provided part of the necessary infrastructure for a political pageant. It was not intended to call attention to itself. It was Gebrauchsmusik, music that served a useful purpose, something Weill had advocated since the 1920s in Germany.

Another 1946 piece by Weill is smaller, but I think it is musically much more important: a setting of the Kiddush (the blessing recited over wine to sanctify the Shabbat or a holiday). This is the only time when Weill as an adult wrote a piece of music intended for actual liturgical use, as against representing worship in a stage production. The short piece for cantor, chorus, and organ was written for New York's Conservative Jewish Park Avenue Synagogue. ("Conservative" Judaism is sort of a middle stream of worship and practice, between Orthodox and Reform Judaism.) Weill dedicated the piece to his father (a cantor, as noted above). It is believed to be the first setting of Jewish liturgical music to deliberately adopt elements of an American musical idiom, in particular a tonal palette drawn from jazz and blues.

Weill's setting of the Kiddush, performed by cantor Azi Schwartz of Park Avenue Synagogue with RIAS Kammerchor, a Berlin-based chamber choir associated with Germany's public broadcasters.

Park Avenue Synagogue was perhaps the only Jewish congregation in the United States that routinely commissioned new settings of the Hebrew liturgy. The synagogue had started this practice in 1943 at the behest of its cantor, David Putterman. Weill's Kiddush premiered as part of their Fourth Annual Service of Liturgical Music by Contemporary Composers. Weill declined any payment for the piece, and even went so far as to waive royalties to allow the synagogue to publish an arrangement. In the next few years he and the Park Avenue Synagogue discussed the possibility of him setting other Hebrew-language liturgical texts. It seems to be a project he wanted to take on, but the next few years were to be very busy, and when he died unexpectedely in 1950, he had never gotten back to the project.

Finally, we should mention one last specifically Jewish work by Weill, this one culturally Jewish rather than a religious piece. In spring of 1947, Weill made what turned out to be the only trip he ever took back to the Old World after settling in America. He visited his parents in Palestine, where Meyer Weisgal (the Zionist leader who had been the impresario of The Eternal Road), introduced him to Chaim Weizmann, a prominent British chemist and president of the World Zionist Organization. Three years earlier, Weizmann had founded the Weizmann Institute of Science, about 12 miles south of Tel Aviv in Rehovot.

Shortly after Weill's visit, plans began to form for a November 25, 1947 dinner and private concert at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in honor of Weizmann's seventy-third birthday. Serge Koussevitzky was to conduct the Boston Symphony Orchestra; the event would be a fundraiser for the Weizmann Institute. Weizmann asked Weisgal to approach Weill about writing an orchestral arrangement of the Zionist anthem "Hatikva" for the occasion. Weill promptly accepted.

The arrangement is certainly a solid one, but it is not quite what one might have expected. As discussed in the liner notes of the Milken Archive's 2007 album In Celebration Of Israel 🔗, it "is not really an accompaniment conducive to communal singing. It seems more like a purely orchestral version—perhaps a brief overture or interlude based on Hatikva—which is how it has been recorded here." That last phrase leads me to think that the recording on that album—the only recording of Weill's setting I've run across—may be an abbreviated version of what Weill wrote. They continue, "The introductory passage gives no clear indication of when the anthem should begin. The melody line becomes buried or otherwise obscured by the harmony in some places. And there is an unexplained 'surprise' interlude before the repetition of the final phrase, which will throw off anyone not expecting it."

All of this is a bit surprising, given the occasion of the performance, and that Weizmann and Weisgal apparently had hopes of ending up with an official orchestration of a soon-to-be national anthem. (Four days after the birthday/benefit, the United Nations would vote to partition Palestine, paving the way to establish the state of Israel; the next year, Weizmann would become its first president.) The Milken Archive liner notes go on to conjecture that Weill may simply have trotted out an existing arrangement he had already done, possibly for A Flag Is Born or as "an interlude or an accompaniment to some form of choreography" The mystery will probably remain, since it is likely that most archival materials related to Weill have been found by now, and nothing has appeared that answers it. In any case, Bernardino Molinari's 🔗 1948 setting of "Hatikvah" has become the standard, not Weill's.

Weill's setting of "Hatikva", performed by the Barcelona Symphony and Catalonia National Orchestra, on the Milken Archive's 2007 album In Celebration Of Israel 🔗.

I can't resist getting into one final aside here. As some of you know, I'm a pretty major contributor to the English-language Wikipedia and its associated media archive Wikimedia Commons, and am an administrator on both. Inevitably, since beginning the Weill Project I've been at least tangentially involved in Wikipedia's article on Kurt Weill—not a bad article but one that certainly could use more work—and others that touch upon his life and works. A year ago, when I started this project, the lede (opening section) of the Weill article made no mention at all of his Jewishness and in a discussion of the matter on the talk page there was an unanswered challenge as to whether, other than The Eternal Road, any of his work beyond juvenalia at age 13 was "distinctly Jewish". I hope that the present post shows how clearly that challenge can be answered. While Weill's specifically Jewish pieces would not, on their own, make him a major figure, his output in this area probably exceeds that of any other Berlin theater songwriter or Broadway composer of his era, despite there being a large number of Jews in both of these groups.

[This essay draws on Jürgen Schebera's meticulously researched Kurt Weill: an illustrated life, (Yale, 1995, translated from the original German by Caroline Murphy), as well as several Wikipedia articles, and Edna Nahshon's piece in the spring 2002 Kurt Weill Newsletter 🔗, "From Geopathology to Redemption", about A Flag is Born, as well as Christian Kuhnt's "Approaching the Music for A Flag Is Born" in the same issue. Also, obviously, I've used the Milken Archive liner notes about Weill's setting of "Hatikva"]

Next blog post: Firebrand

Next Weill biography blog post: Firebrand