By date

- 8 March 2021: Welcome!

- 9 March 2021: Kurt Weill and John Cale

- 18 March 2021: Happy Birthday, Kurt Weill!

- 26 March 2021: Working on "Mussel From Margate" and "Jealousy Duet"

- 03 April 2021: The Young Kurt Weill in Dessau

- 16 April 2021: Weill's Student years (1)

- 26 April 2021: Face-to-face!

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 20 May 2021: Novembergruppe

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 28 June 2021: Schickelgruber (song)

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 12 July 2021: What Is 'Epic Theater'?

- 15 July 2021: What Keeps Mankind Alive? (song)

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 25 July 2021: Speak Low (song)

- 2 August 2021: Youkali (song)

- 9 August 2021: François Villon

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 23 August 2021: Not exactly a manifesto

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 18 October 2021: Kurt Weill and shadow puppetry

- 25 October 2021: Summer 1933

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 8 November 2021: The Eternal Road

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 13 December 2021: One Touch of Venus

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 3 January 2022: Jewish Kurt Weill

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- 28 February 2022: Down in the Valley

- 14 March 2022: Love Life

- 28 March 2022: Lost in the Stars

Kurt Weill biography

- 03 April 2021: The Young Kurt Weill in Dessau

- 16 April 2021: Weill's Student years (1)

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 25 October 2021: Summer 1933

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 8 November 2021: The Eternal Road

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 13 December 2021: One Touch of Venus

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 3 January 2022: Jewish Kurt Weill

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- 28 February 2022: Down in the Valley

- 14 March 2022: Love Life

- 28 March 2022: Lost in the Stars

Lotte Lenya biography

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

By topic

- Agnes de Mille

- Alabama Song

- Alan Jay Lerner

- Alan Paton

- Arnold Sundgaard

- Baden-Baden

- Ben Hecht

- Berlin

- 16 April 2021: Weill's Student years (1)

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 20 May 2021: Novembergruppe

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- Berlin Im Licht

- Berliner Requiem

- Bertolt Brecht

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 12 July 2021: What Is 'Epic Theater'?

- 15 July 2021: What Keeps Mankind Alive? (song)

- 9 August 2021: François Villon

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- Broadway opera

- Caspar Neher

- Charles Lindbergh

- Complainte de la Seine

- Danny Kaye

- Darren Loucas

- David Drew

- Der Neinsager

- Der Protagonist

- Die Bürgschaft

- Down in the Valley

- Dresden

- East Portland Blog

- Elia Kazan

- Elisabeth Hauptmann

- Elmer Rice

- Engelbert Humperdinck

- Epic theater

- Erika Neher

- Erwin Piscator

- Eternal Road

- Expressionism

- Felix Jackson

- Firebrand of Florence

- Franz Werfel

- Frauentanz

- Fritz Busch

- Georg Kaiser

- George Antheil

- Georges Rouault

- Gertrude Lawrence

- Hannah Höch

- Hans Curjel

- Hollywood

- Hyperinflation

- Ira Gershwin

- Ivan Goll

- Jealousy Duet

- Jean Cocteau

- Jewish Kurt Weill

- Joe Mabel

- 8 March 2021: Welcome!

- 9 March 2021: Kurt Weill and John Cale

- 26 March 2021: Working on "Mussel From Margate" and "Jealousy Duet"

- 16 April 2021: Weill's Student years (1)

- 26 April 2021: Face-to-face!

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 20 May 2021: Novembergruppe

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 28 June 2021: Schickelgruber (song)

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 12 July 2021: What Is 'Epic Theater'?

- 15 July 2021: What Keeps Mankind Alive? (song)

- 25 July 2021: Speak Low (song)

- 2 August 2021: Youkali (song)

- 9 August 2021: François Villon

- 23 August 2021: Not exactly a manifesto

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 25 October 2021: Summer 1933

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 8 November 2021: The Eternal Road

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 13 December 2021: One Touch of Venus

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 3 January 2022: Jewish Kurt Weill

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- 28 February 2022: Down in the Valley

- 14 March 2022: Love Life

- 28 March 2022: Lost in the Stars

- Johann Gottfried Herder

- John Cale

- Juliana Brandon

- 8 March 2021: Welcome!

- 18 March 2021: Happy Birthday, Kurt Weill!

- 26 March 2021: Working on "Mussel From Margate" and "Jealousy Duet"

- 26 April 2021: Face-to-face!

- 28 June 2021: Schickelgruber (song)

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 25 July 2021: Speak Low (song)

- 2 August 2021: Youkali (song)

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 23 August 2021: Not exactly a manifesto

- 18 October 2021: Kurt Weill and shadow puppetry

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

- Kuhhandel

- Kurt Weill

- 8 March 2021: Welcome!

- 9 March 2021: Kurt Weill and John Cale

- 18 March 2021: Happy Birthday, Kurt Weill!

- 26 March 2021: Working on "Mussel From Margate" and "Jealousy Duet"

- 03 April 2021: The Young Kurt Weill in Dessau

- 16 April 2021: Weill's Student years (1)

- 26 April 2021: Face-to-face!

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 20 May 2021: Novembergruppe

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 24 June 2021: Brecht (1), Mahagonny Songspiel

- 28 June 2021: Schickelgruber (song)

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 12 July 2021: What Is 'Epic Theater'?

- 15 July 2021: What Keeps Mankind Alive? (song)

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 25 July 2021: Speak Low (song)

- 2 August 2021: Youkali (song)

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 23 August 2021: Not exactly a manifesto

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 18 October 2021: Kurt Weill and shadow puppetry

- 25 October 2021: Summer 1933

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 8 November 2021: The Eternal Road

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 13 December 2021: One Touch of Venus

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 3 January 2022: Jewish Kurt Weill

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- 28 February 2022: Down in the Valley

- 14 March 2022: Love Life

- 28 March 2022: Lost in the Stars

- Léo Lania

- Lüdenscheid

- Lady in the Dark

- Langston Hughes

- Lost in the Stars

- Lotte Lenya

- 31 May 2021: Der Protagonist

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- Lotte Reiniger

- Love Life

- Lys Symonette

- Mahagonny

- Man Without Qualities

- Marc Blitzstein

- Marlene Dietrich

- Mary Martin

- Maurice Abravanel

- 5 May 2021: Weill's Student years (2)

- 13 May 2021: Weill's Student years (3)

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- Max Reinhardt

- Maxwell Anderson

- Meyer Weisgal

- Moss Hart

- Mussel From Margate

- Nazizeit

- New York

- One Touch of Venus

- Otto Dix

- Otto Pasetti

- Paris

- Princess du Polignac

- Robert Vambery

- Roger Fernay

- S.J. Perelman

- Scherenschnitte

- Schickelgruber

- Seven Deadly Sins

- Shadow puppetry

- Silbersee

- Street Scene

- Threepenny Opera

- Tilly Losch

- Weill Project

- 8 March 2021: Welcome!

- 9 March 2021: Kurt Weill and John Cale

- 18 March 2021: Happy Birthday, Kurt Weill!

- 26 March 2021: Working on "Mussel From Margate" and "Jealousy Duet"

- 26 April 2021: Face-to-face!

- 14 June 2021: Transformation

- 28 June 2021: Schickelgruber (song)

- 5 July 2021: Brecht (2), Threepenny Opera

- 15 July 2021: What Keeps Mankind Alive? (song)

- 20 July 2021: Lotte Lenya & Nanna's Lied

- 25 July 2021: Speak Low (song)

- 2 August 2021: Youkali (song)

- 16 August 2021: Lotte Lenya and the road to Threepenny Opera

- 23 August 2021: Not exactly a manifesto

- 30 August 2021: Brecht (3) and… Charles Lindbergh?

- 13 September 2021: Brecht (4): Rise and Fall of the City

- 20 September 2021: Brecht (5): Jasager & Neinsager

- 27 September 2021: Die Bürgschaft

- 4 October 2021: Standing on the Verge

- 11 October 2021: Paris (1): an expedient harbor

- 18 October 2021: Kurt Weill and shadow puppetry

- 25 October 2021: Summer 1933

- 1 November 2021: Paris (2): Sojourn

- 8 November 2021: The Eternal Road

- 15 November 2021: New York, New York

- 22 November 2021: Lotte Lenya from Threepenny Opera to America

- 29 November 2021: A period of adjustment

- 6 December 2021: Lady in the Dark

- 13 December 2021: One Touch of Venus

- 20 December 2021: Wartime

- 3 January 2022: Jewish Kurt Weill

- 17 January 2022: Firebrand

- 31 January 2022: Broadway Opera

- 14 February 2022: Street Scene

- 28 February 2022: Down in the Valley

- 14 March 2022: Love Life

- 28 March 2022: Lost in the Stars

- Weill Project Blog

- Weill family

- Weill's Second Symphony

- What Keeps Mankind Alive

- What Was Sent to the Soldier's Wife

- World War II

- World War II propaganda

- Young Kurt Weill

- Yvette Endrijautzki

- Zeitoper

- degenerate art

Tags

#kurtweill #arnoldsundgaard #downinthevalley #joemabel #weillproject #weillbio

(Prior biographical posts on Weill: [1],

[2],

[3],

[4],

[5],

[6],

[7],

[8],

[9],

[10],

[11],

[12],

[13],

[14],

[15],

[16],

[17],

[18],

[19],

[20],

[21],

[22],

[23],

[24],

[25],

[26].

Growing up, I certainly did not know Weill's opera Down in the Valley, but I was very familiar with the song it expands upon. My father sang it often,

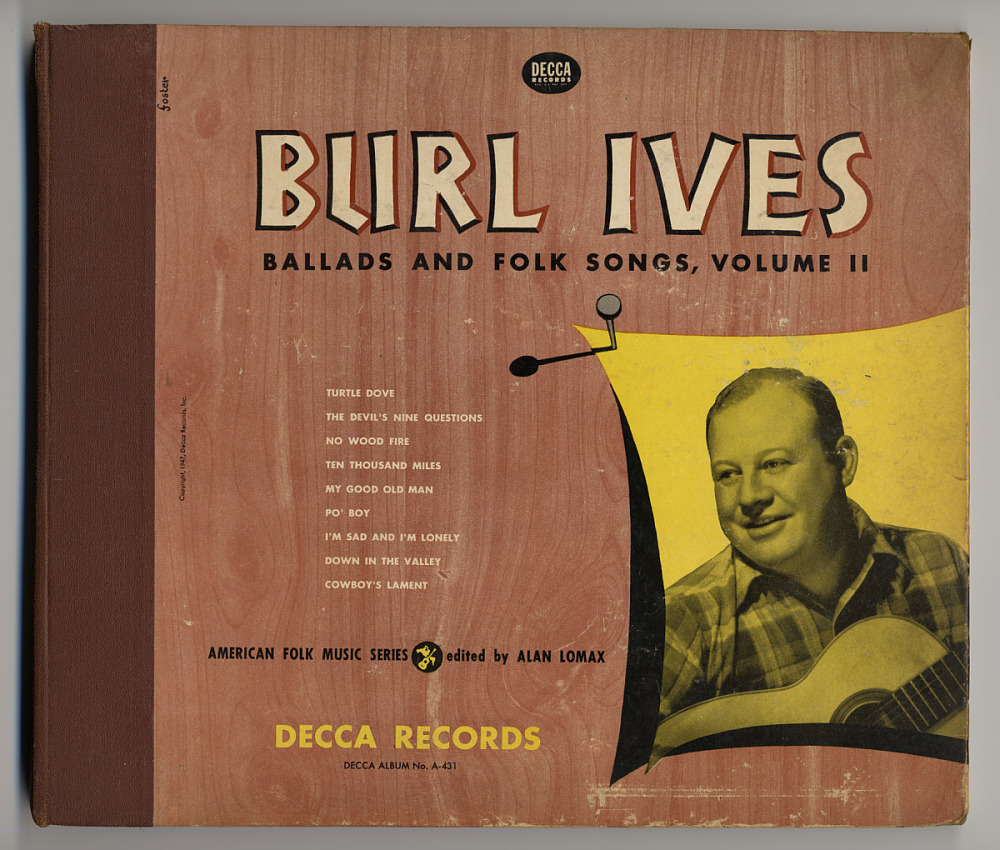

accompanying himself on guitar. I think he learned it from this Burl Ives record.

Decca Records, copyright status unknown. Used on a fair use basis.

This is the one I'd rather not write. Down in the Valley 🔗 is the one Kurt Weill theater piece I know and don't like. It's not that I think it is completely without merit, and it's not like I'm uniformly against classical-music approaches to American folk themes (I'm fine with Appalachian Spring 🔗), and I even have affection for certain rather "dated" forms of musical theater like Weill's patriotic and Zionist pageants that came only a few years before. It just rubs me the wrong way.

I certainly grew up knowing the folk song "Down in the Valley" that was the origin point of this "American folk opera" (to use Weill's own designation). I remember my father singing the song and playing it on the guitar. He basically did Burl Ives' version (here on YouTube 🔗), though with a slightly simpler melody and a less delicate voice. I think it was one of the saddest songs that he sang, even more so than songs about death of a lover. I never concerned myself much with why the point-of-view character is in jail; just that he is clearly without much hope, and (I realized this as I got a bit older) isn't even hoping for love, just for a trace of comfort: "If you don't love me, / Love whom you please. / Throw your arms 'round me. / Give my heart ease." That last aspect is really missing from the Weill / Arnold Sundgaard expansion of the song into an opera. However, they certainly did take up the whiff of death in "Angels in Heaven / Know I love you."

There were actually two forms of the opera Down in the Valley: a roughly 20-minute piece written in 1945 with the (unfulfilled) intention of a radio broadcast, and a piece roughly twice that length written in 1948 premiered by the opera department of Indiana University School of Music. The longer version has been recorded several times and performed thousands of times, mostly in the decade after it was written; I don't think the shorter version is ever performed, or at least quite rarely. I know the opera from a 1950 recording (I think from an NBC radio broadcast), which now that I look is only about 30 minutes long, so it might be slightly abbreviated. Then again, the only recording supposedly of the whole piece that I see online (here, on Youtube 🔗) is the same length, so maybe it's simply shorter than my sources say, or maybe these compromise somewhere between the two "official" versions.

Obviously, this project was another of Weill's efforts to create "American opera". Whereas Street Scene was urban, multi-ethnic and multi-racial, musically varied, and rooted in a combination of European operatic tradition and Broadway, Down in the Valley is rooted in the Scots-Irish folk traditions of the Appalachians and Ozarks. This wasn't the first time Weill worked with American folk material, and of course he had worked extensively with European Jewish folk material for The Eternal Road and for the several Zionist pageants he worked on with Moss Hart and others. Weill had used American folk material in Railroads on Parade (written 1939 for the New York World's Fair, expanded 1940) and also for some of his projects around that time with Maxwell Anderson (Ballad of the Magna Carta and, especially, Your Navy, which used sea shanties and war songs.

But, really, the original impetus for Down in the Valley came from outside, and Weill's involvement, in Stephen Hinton's words, "mixed idealism and opportunism in equal measure." In 1945, the veteran (and rather musically conservative) music critic Olin Downes 🔗 approached Weill with the idea of "finding a new artistic form through which American composers might evolve a native art by utilization for dramatic purposes of American folksong." Downs had approached advertising executive Charles McArthur about doing a series of such pieces for radio, each to dramatize a folksong. The basic concept was to find an equivalent of the old British form of "Ballad opera", such as John Gay's Beggar's Opera (1728), which had formed the basis for the Brecht/Weill Threepenny Opera two centuries later.

(By the way, I haven't been able to work out just who Charles McArthur was: what firm he was with, etc. I've see several articles that clearly misidentify him, including conflating him with the playwright Charles MacArthur 🔗.)

Downes and Weill agreed on Arnold Sundgaard 🔗 as librettist. Sundgaard and Weill apparently worked well together, pretty comfortable with a division of duties where Sundgaard focused very much on a libretto and trusted Weill to make all the musical decisions. The piece was completed, there were apparently several informal performances in New York on a "house concert" scale, and they even made what in radio is known as an "audition recording", but they never found sponsors. For the moment, Down in the Valley was consigned to the drawer.

A few years later someone (there seems to be some disagreement as to who) approached Weill about a longer one-act opera suitable for performance at a college. It might have been Hans Busch (in which case it definitely would have been intended from the start for Indiana University, where it was first performed) or it might have been Hans Heinshemer at Weill's publisher Schirmer (but Heinshemer's version of events ignores the existence of the prior radio version, so it's hard to know whether to credit it at all). In any event, a serious proposal came together, and Weill and Sundgaard got back to work on the piece.

As Stephen Hinton remarks, the song "Down in the Valley" isn't much of a narrative. Sundgaard's libretto drew on two elements: love and imprisonment. It also drew on several other folk songs: "Lonesome Dove," "The Little Black Train," "Hop Up, My Ladies," and "Sourwood Mountain." Weill and Sundgaard cited the 1939 book Singin' Gatherin' as a source for all of these, but we know that they researched many versions. Presumably they didn't mention others publicly for legal reasons: anything copyrighted from which they picked lines or musical themes could have come after them for royalties. In additon to "Down in the Valley" and the four other songs just mentioned, Weill wrote two entirely new songs in a reasonably convincing American folk style: "Brack Weaver, My True Love, They've Taken Away" and "Where Is the One Who Will Mourn Me When I'm Gone?"

The plot is simple. In an unspecified Appalachian town, Brack Weaver falls in love with Jennie after a prayer meeting. Both are in their late teens. Jennie's father has been trying to use her charms to appease his creditor Thomas Bouché. The father tells Jennie to go to a dance with Bouché, but she goes with Brack. Bouché gets drunk and threatens Brack with a knife. Brack, defending himself, ends up killing Bouché with the latter's own knife. Brack is convicted of murder and condemned to hang. The night before his scheduled execution, he escapes to see Jennie one last time. Believing that any effort to really run away will just result in being caught, he turns himself back in to be hanged. The story is told mostly in flashback, with its "present" being the time Brack spends with Jennie before turning himself back in.

In some ways, despite a very different setting and idiom, it is a throwback to the Lehrstücke Weill wrote with Brecht, notably Der Jasager. It is relatively simple; it is intended at least as much to teach singing and performing as it is intended for an audience; and it is about a young person bravely facing death. It does introduce a romantic element completely missing from Brecht's Lehrstücke, and it is more sentimental and less ironic. The latter, of course, could be said about the bulk of Weill's American work when compared to his work with Brecht. Still, despite a few very Hollywood-ish passages, it is much more austere than Weill's other American work.

I happen to have taken this picture of John Rockwell in 2015 at the Pop Conference in Seattle. I took it for Wikimedia Commons; never expected to have a use for it myself, but now I do!

Photo by Joe Mabel, licensed under CC-BY-SA 3.0

I should note that even though I'm not a fan of Down in the Valley, it has its moments. The church scene (the first flashback) is solid. Bouché's menacing version of "Hop Up, My Ladies," establishes him well as a villain. "Sourwood Mountain" works nicely for the scene at the dance, and as the fight breaks out the dissonant violin part evolves nicely out of the folk melody. Still, though, there is the sentimentality. In a mostly favorable review ("Weill's witty, musicianly development of folk themes…"), Time magazine nonetheless noted, "some customers feel that the libretto should have been poured over a waffle instead of an audience." I think I find myself in that camp. The song that inspired the opera is genuinely sad, but it isn't mawkish. As I've remarked before, Weill had a tendency toward sentimentality that did not necessarily work well with libretti that already leaned that way on their own. (After writing that, I ran across almost exactly the same view in John Rockwell's New York Times review 🔗 of a 1984 Channel 4/London and Unitel/Munich performance, broadcast on New York's public Channel 13: "The deliberate näivete here is too extreme: Weill's sentimentality needed the balance of a sharper, wittier, more ironic mind…")

In any case, the piece was a surprising commercial success. There were 80 productions its first year, mostly at colleges, and 1500 by the late 1950s, including a 1949 hit for New York's Lemonade Opera Company, probably that company's biggest sucess ever. It was broadcast in 1948 by NBC radio and 1950 by NBC television. I imagine there were many others. Weill definitely saw Down in the Valley as another serious step toward his idea of creating American Opera ("Everything I have done so far has been working toward this"). When you consider that at the end of his life two years later he was working on an opera of Huckleberry Finn and had seriously considered Moby Dick, that makes a certain sense; of course, both of those would have given him much stronger scenarios.

Pretty much every critic I can find writing about Down in the Valley notes the contrast between Weill's compositional style and the folk material he is working with. Critics disagree more in their opinion of that than in their analysis. Probably the cruelest is David Drew: "gobbets of undigested Wagner or Puccini are lumped together with stock Tin Pan Alley formulae [and] empty ostinati." At the other extreme, Wilfred Bain 🔗, then dean of the Indiana University School of Music, apparently loved Weill's "learned and skillful orchestral treatment" of folk melodies and, similarly, Stephen Hinton refers to the "dovetailing of simple folk melodies and the melodrama of grand opera."

Hinton finds "tragedy, but affirmation" (the affirmaiton of love) in the opera taken as a whole, and in its ending in particular. I'm afraid I mostly find something that feels like a warmup for something larger and stronger that Weill didn't live to achieve.

[This essay draws heavily on Stephen Hinton's Weill's Musical Theater: Stages of Reform (University of California, 2012).]

Next blog post: Love Life

Next Weill biography blog post: Love Life